By Susan Montoya Bryan, The Associated Press

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — Janay Jumping Eagle is on a mission to curb teen suicide in her hometown on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Dahkota Brown of the Wilton Band of Miwok Indians in California wants to keep American Indian and Alaska Native students on track toward graduation.

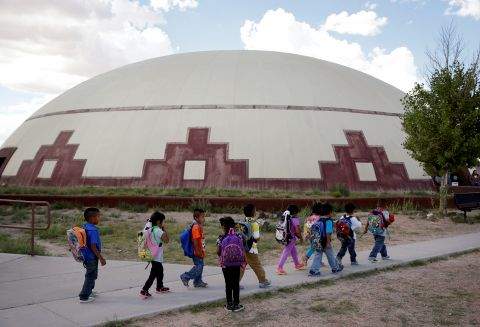

The teenagers are at the heart of Generation Indigenous, or Gen-I, a White House initiative that kicked off this week with a brainstorming session that happened to coincide with tens of thousands of indigenous people gathering in New Mexico for the Gathering of Nations, North America’s largest powwow.

The Generation Indigenous program stems from a visit last year by President Barack Obama to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Meetings followed, the president called for his cabinet members to conduct listening tours, tribal youth were chosen as ambassadors and a national network was formed.

The goal is to remove barriers that stand in the way of tribal youth reaching their potential, said Lillian Sparks Robinson, a member of the Rosebud Sioux and an organizer of Thursday’s Gen-I meeting.

“This is a community-based, community-driven initiative. It is not something that’s coming from the top down. It’s organic,” she said.

The teens are coming up with their own ideas to combat problems in their respective communities.

For example, a string of seven suicides by teenagers in recent months has shaken Pine Ridge, and close to 1,000 suicide attempts were recorded on the reservation over a nearly 10-year period. Jumping Eagle, a high school sophomore, said her older cousin was one of them.

“That was really devastating. I just wanted to at least try to stop it from happening and I’m still trying,” she said, noting that a recent basketball tournament she organized as part of her Gen-I challenge to bring awareness and share resources with schoolmates was a success.

Brown, 16, said he sees Gen-I as a tool to “shine a light on the positive things that are happening in Indian country rather than all the other bad statistics that go along with being a Native teen.”

From New Mexico’s pueblos to tribal communities in the Midwest and beyond, federal statistics show nearly one-third of Native youth live in poverty, they have the highest suicide rates of any ethnicity in the U.S., and they have the lowest high school graduation rate of students across all schools. And for American Indians and Alaska Natives overall, alcoholism mortality is more than 500 percent higher than the general population.

Federal agencies are working with the Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute to pull off Generation Indigenous, and the White House is planning a tribal youth gathering in July in Washington, D.C.

In one of her last tasks before passing on the Miss Indian World crown, Taylor Thomas spoke to Gen-I participants Thursday. She shared with them her tribe’s creation story, which centers on the idea that every animal, plant and person has a purpose. She encouraged the teens to be leaders.

“No matter the difficulties we have in our communities, we have so many bright lights shining from all over Indian country. And when I say that I’m talking about all of you,” she told the crowd of about 300.