By Roxana Popescu, The San Diego Union-Tribune

The old man wasn’t book smart, but he was wise. When birds sang, he listened. When he told stories, everybody listened. Pat Curo especially remembers how his grandfather always encouraged him to learn their native Kumeyaay dialect. Even when others objected. Even when it didn’t come easily.

Those were the days of assimilation. Indians stopped speaking their language because they saw English was the way to get ahead. Parents told children: “Don’t try. Speak English,” Curo said.

At the Barona Indian Reservation in Lakeside, the tables are turning. Curo, now more than 50 years older, was recently encouraging his daughter, granddaughter and several other language students to speak Kumeyaay. Workbooks and dictionaries were scattered around them, and the tribe’s chairman stopped by to check up on their progress.

It’s a scenario being repeated across San Diego’s reservations, and California’s: Steady or growing numbers of people are taking language classes, from none or just a handful decades before, said people from the Sycuan, Viejas and Barona bands. High schoolers and even younger children are showing up for classes, with or without their parents.

“There’s a statewide renaissance that many tribes are participating in,” said Marina Drummer, with Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival, an educational and promotional organization. “Virtually all tribes are making an effort to preserve this piece of their culture.”

Whereas before speaking a native Indian language was seen as undesirable, “it’s become something to be proud of,” said Mandy Curo de Quintero, Curo’s daughter. She’s teaching her two daughters the Iipay dialect through courses, activities at home and CDs she plays in the car, which she uses for better pronunciation.

Based on anecdotes like these, there’s talk on local reservations of a resurgence. Not so fast, counters Margaret Field, a professor of American Indian Studies at San Diego State University who studies American Indian languages.

“Kumeyaay is down to about 100 fluent speakers, most of whom live in Baja. You can use whatever adjectives you like, that’s the empirical number,” Field said in an email interview. “All indigenous languages around the world are endangered, in that they could disappear within a generation or two.”

And Kumeyaay, part of the most ancient language family of California, is no different. All that keeps it from oblivion are three delicate threads: the memory of a few dozen fluent speakers, these elders’ willingness to teach, and the enthusiasm and dedication of their students.

“As far as its future goes, it’s up to the last 100 speakers. They have to start speaking it to children, as many children as possible, as quickly as possible, and just keep it up,” Field said.

Why they bother

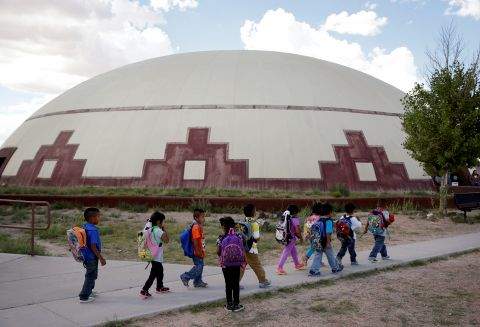

Speakers and students of Yuman languages (Kumeyaay, spoken by some local tribes, is a Yuman language) recently got together for an annual Yuman Language Summit, held this year at Barona. They live all across California and Baja California, and up the Colorado River and into the Grand Canyon.

Cecelia Medrano, a member of the Fort Mojave tribe, traveled almost five hours from Needles, with her grown daughter, to find out how others are preserving their languages. In her community, she said, maybe 25 people are still fluent.

“I thought I’d come and see exactly how it is — how some of the other tribes are trying to rectify that. It’s important. You can’t let it die. Because if it dies, what do you stand for?” Medrano said.

A cynic or even a pragmatist might ask: Why bother? English is the language spoken by most people in the United States, and Spanish is common locally. Why labor to learn a language that has no word (unless you count recent coinages) for television or email? A language almost no one else speaks?

Students of Kumeyaay echo the claims of people who study other languages, living or dead: knowing a language means knowing a culture. In the Iipay dialect of Kumeyaay, Curo said, the same word represents earth and dirt — amut. That’s also the word for human. “Because we come from the ground,” he said. That vocabulary “shapes your vision, your perspective on life.”

Charlene Worrell, a tribal leader with Sycuan, decided to learn Kumeyaay because the tribe’s history and values are shared through songs, not writing.

“I’ve come to realize that our language is kind of poetic, in a way,” Worrell said. Instead of an equivalent of “hello” or “good day,” the Kumeyaay greeting, haawka, means “may that fire in you burn bright.”

One session at the Yuman language conference showed how language and philosophy could be said to inform one another. O’Jay Vanegas, a museum educator with Barona, gave a talk about a game of Monopoly he helped develop, where the goal is for people to speak in Kumeyaay. They learn vocabulary and hop from square to square, counting aloud. Just as important, he said, is the way the game teaches players about an alternative value system.

“The concept is totally opposite of the capitalist-based philosophy of Monopoly. This is more communal,” Vanegas said. Instead of buying utilities, for example, players pay to be custodians of natural resources — acorns or water. In this Native American take on the game, there’s no jail, but players get detained on “vision quests.”

Early start

Drummer, with the statewide Indian cultural group, said it’s hard for tribes to revive languages when few people are fluent, and when there are so many different groups and languages. Unlike with Spanish or Hawaiian, you need many different textbooks and dictionaries, not just one. “It’s a big challenge, for sure,” Drummer said.

Another challenge: A generation or two ago, people didn’t learn indigenous languages because of the stigma, members of various local tribes said. Today that reputation has changed, but there’s a new obstacle: distraction.

Like many others in the age of streaming Internet, Breeana Donayre, 15, is tempted by Netflix binges or whiling away her hours online. Yet studying her ancestral language has somehow kept her interest.

“I just think it’s cool to be able to speak the same language as my past family and everybody. It’s cool to, like, know a part of them is kind of in me,” Donayre said. Language exercises are more fun than her other homework, she added.

Members of the Viejas band realized it’s important to hook language learners when they’re young. Anita Uqualla, a teacher, persuaded tribal leaders to fork over about $35,000 to a company that develops iPhone applications. In November 2012, the tribe released a free Kumeyaay language app, with audio recordings and learning tools.

“We needed to have a way to reach our young people, so we decided to use the media, and the app was perfect for that,” Uqualla said. Uqualla didn’t have information about downloads or usage, but she said the tribe’s educational programs use it.

Stan Rodriguez, a Kumeyaay language teacher from Santa Ysabel, shared a recent anecdote — a small triumph from a few years ago. The language then, like today, was endangered, but it was rarer to see young people in classes. A group of junior high school boys seemed totally uninterested in what he was teaching.

“In one ear and out the other,” Rodriguez said. But then, a week later, he got a call from the school principal, who was concerned. They boys were overheard saying cheeky things about the school bus driver — in Kumeyaay.