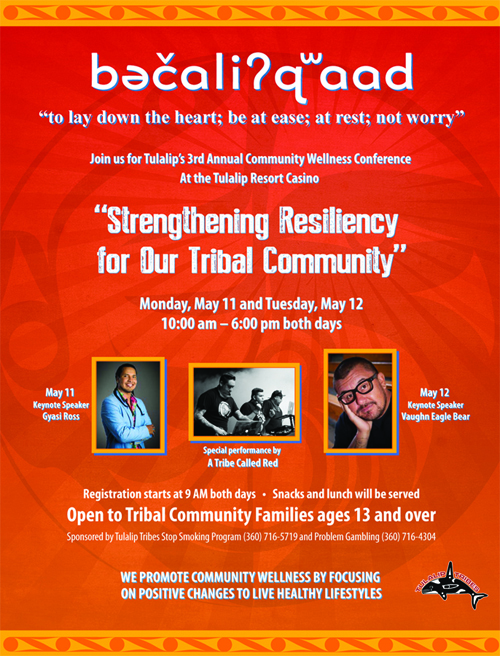

Photo courtesy of Gyasi Ross.

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

As part of the Community Wellness Conference that took place on May 11 at the Tulalip Resort, keynote speaker Gyasi Ross gave an impassioned speech directed at Tulalip’s high school youth. Ross is a member of the Blackfeet Nation of the Port Madison Indian Reservation where he resides. He is a father, an author, a speaker, a lawyer and a filmmaker. TV, radio and print media regularly seek his input on politics, sports, pop culture and their intersections with Native life. For those who were unable to attend the conference and as a result were unable to hear Ross’s keynote address, the following is the most powerful message he delivered to the Tulalip youth on their history, biology, and purpose as a member of a Native community.

“I want to acknowledge the staff who put this event on. Most school don’t have stuff like this because there is no money for stuff like this. We all know money is important, which means the tribes is investing in you all by putting this money forth; they are saying you all are important. How do you know when something is important to somebody? Unfortunately, it’s because they spend money on it. That’s what people value in today’s society.

All of us come from a history and a culture, a culture that acknowledges where we are. History is a fancy word for ‘this is where I come from’.

One of my favorite quotes in the world is from an Okanogan woman named Christine Quintasket. She was the first Native woman to ever publish a written book. She had an amazing outlook on life where she viewed life’s function as a part of the natural world. She liked to talk about the relationship of human being to nature, to trees and plants and to the animals. Christine Quintasket said, ‘Everything on Earth has a purpose, every disease an herb to cure it, and every person a mission.’ If this quote is true, and I believe it is true, then that means every single one of you guys and girls and women and men and me, has a purpose. Every single one of us has a mission. What purpose or mission do you have?

Let’s talk a little biology. If I look at my grandparents, three of my four grandparents were alcoholics. That means I have a 75% of carrying something similar to them that would make me like alcohol. As a result of that both my parents at one time were alcoholics. As a result of that I’ve chose never to drink, I’ve never driven alcohol in my life. It’s not a religious thing, I’m not religious at all, but it’s a practical recognition of history, of Mendel’s Grid, of biology. That’s why it’s important to understand biology and to understand our history. It’s because that helps informs who you are.

Going into biology a little bit more, how many of you have ever said or heard someone say, ‘I didn’t choose to be here!” How many of you have said that yourself, that you did not choose to be here? I know I’ve said that before. I’m going to tell you why that statement is dead wrong. Biology. Every time a baby is conceived a man releases from 80 to 500 million sperm cells. It’s fact. That means that for every single one of you, before you were conceived, you were in BIG competition. You were in competition with 80 to 500 million other sperm cells trying to get to that egg…and YOU won. Every single one of you are that special little sperm cell that was stronger, quicker and more agile than everyone else. You wanted to be here! I’m not talking religion. As a matter of biological fact, every single one of you wanted to be here.

That means anytime you say or you start to say, ‘I didn’t choose to be here’ you are lying, you are not telling the truth. With that we are going to go into some history.

The function of tribes, of Native people who lived in small, intimate communities who lived in distinct places. The reason we chose to live in these small, intimate communities was for survival. For no other reason than survival. It was based on interdependency. Everyone in the community had a role, a function within the community, and those communities were successful because each member was able to depend on the other members to live up to their roles. The hunters, the fisherman, the gathers, the clothes makers, those who were able to make medicines…whatever their responsibility within the community they had to live up to it because everyone else’s survival depended on them.

Going back to the notion of Christine Quintasket saying, ‘Everything on Earth has a purpose, every disease an herb to cure it, and every person a mission.’ It is inherent, inherent is a fancy word that says it’s written within out DNA and it’s in our blood, it is inherent as Native people to have a mission. Every single one of us, every single one of you, has a mission. Once again, what is your mission? Going back to the historical times, our ancestral communities, those missions were hunting, gathering, medicinal herbs, being a warrior, seam-stressing, etc. This is something that is also historically proven, every single one of you are necessary. You are necessary to the betterment and survival of the whole. This is what we are talking about when we say culture.

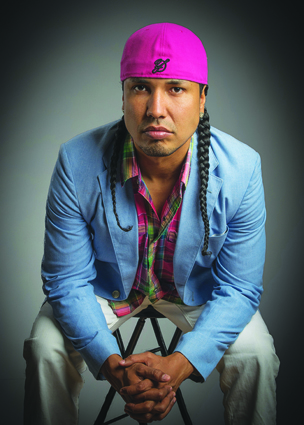

Photo/Micheal Rios

A lot of people think culture is this fancy thing that you wear, it’s a pendent or beaded necklace. One of my heroes, his name is John Mohawk, said ‘Culture is a learned means of survival in an environment’. That’s all it is. At one time when you were trying to survive as that special little sperm cell, you were kicking and fighting and elbowing all these other 80 to 500 million sperm cells because your means of survival was getting to that egg by any means necessary. As we developed and we became tribes, our means of survival was by finding what the need was within our community. We all come from need-based communities. From both these perspectives, historically and biologically, you are necessary, you are important, and you are beautiful.

A side note to the historical piece. I don’t get into the morality of drugs and alcohol, the morality of it and spiritual part is between you, your family and your creator. However, there is a practical part.

The practical part is historically our people couldn’t afford to do things that weaken themselves. You couldn’t do it as a practical matter, not as a spiritual matter. You couldn’t be weak. Why? Because when you are coming from a small community and there are only so many hands that can go out and hunt, or so many hands that could go out and gather food and medicinal herbs, or so many hands that can seamstress…every person is a commodity. Every person is incredibly important. For every single person who is unable, because they are weakened by drinking alcohol or doing drugs, that isn’t able to fulfill their function within the community is making the entire community weaker. Not morally, but practically because that makes their family and their community weaker by that individual’s decision to weaken themselves, because now they can’t be relied upon to carry word or to go fish or to hunt. So now the community as a whole is weaker. Every single one of you are necessary in a community.

You need this place, your community, your home…and it needs you. The reason why you need this place is because history and biology. Right now, you have the privilege of breathing the same oxygen, drinking the same water, eating the same fish as your ancestors have for 20,000 years. Nobody else in this country can say that. There’s not one single person in this nation who can say that other than Native people. That’s it. That’s a huge privilege. Your community has that sense, that longing, it’s that Mother Land that says, ‘I need you, but you also need me’. When we look at the history, the biology of these communities there is a DNA there and you are the living embodiment of that DNA.

I want to end with Christine Quintasket. ‘Everything on Earth has a purpose, every disease an herb to cure it, and every person a mission’. What is your mission?”