Credit: Photo by Suzette Brewer

There’s no way to quantify the damage, but tribal leaders estimate it’s in the billions. “It happens every day in every native community; it’s that common,” says Jodi Gillette, former special assistant on Native American Affairs to the White House.

By Suzette Brewer, WeNews Correspondent

STILWELL, Okla. (WOMENSENEWS)– For six years Brendan Johnson served as U.S. attorney for the State of South Dakota.

During his time as federal prosecutor, Johnson says fully 100 percent of the women and girls engaged in the sex trafficking industry were victims of rape and-or sexual abuse earlier in their lives.

“We had an underage girl from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota who was picked up in Sioux Falls and wound up in a sex ring,” said Johnson, who is now in private practice, in a phone interview from his office in Sioux Falls, S.D. “She was a single mother and had not a penny to her name, which is very common. She didn’t want to rely on government assistance because of the fear that her child would be taken away. She had also been sexually abused prior to this. So the high economic impact of these situations is hard to accurately quantify, because of post-traumatic stress disorder and the related issues for girls who are vulnerable targets for these criminals.”

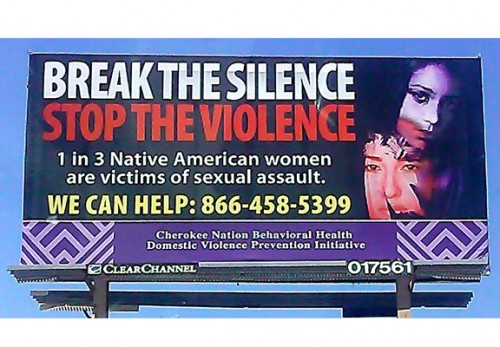

Tribal women are the most vulnerable group of women when it comes to rape; nearly three times as likely to suffer sexual assault than all other races in the United States, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice.

“It happens every day in every native community–it’s that common,” says Jodi Gillette, the former special assistant on Native American Affairs to the White House. “I know literally dozens of women who have told me at one point or another that they were raped or sexually abused, but no one talks about it because of the stigma. So they suffer in silence.”

Gillette, who now serves as a tribal policy advisor for the Sonosky Chambers law firm in Washington, D.C., recently testified at the U.S. Permanent Mission to the United Nations in Geneva that even with recent passage of the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010 and the Violence Against Women Act of 2013, which closed jurisdictional gaps and allowed non-tribal perpetrators to be tried in tribal courts, much work remains to be done.

Basic Services a Struggle

“Many tribes struggle to provide basic victims services, necessary training and staff for courts and adequate mental health care,” said Gillette in a recent phone interview. “To this day, tribes still cannot prosecute non-Indians for child abuse, rape and other serious crimes against women and children and must rely on the federal authorities, who usually only prosecute the worst crimes. This leaves vulnerable many Indigenous women and children unprotected in their own homelands.”

Nearly one-third of tribal women, or approximately 875,000 nationwide, report being raped at some time in their lives. Two-thirds of their perpetrators are non-Indian, who until very recently could not be prosecuted in tribal court and are still unlikely to ever face formal charges for their crimes in state or federal court. This is due, in part, to the fact that–despite the recent expansions of tribal court to prosecute rape–many smaller and-or remote tribes either do not have their own tribal court systems and do not have the resources to establish one.

The scourge of rape in Indian country has impacted every single community among the nation’s 567 federally-recognized tribes, whose total population hovers around 5.2 million.

The costs–both emotional and financial–are staggering for communities already beset by poverty and its attendant social problems in geographically isolated regions.

The American College of Emergency Physicians, based in Irving, Texas, estimates that the tangible costs of rape–for both the victim and the society–are approximately $150,000 per victim. That amount covers a range of categories including expenses for justice and prosecution, physical and mental health issues for the woman and her family, social services including emergency response teams and shelters, loss of education, loss of wages and/or employment.

Emotional costs, including pain and suffering for the victim and her children, possible death of the victim, including suicide and others, are incalculable.

Native American writer Louise Erdrich, in her 2012 book “The Round House,” tells the story of Geraldine Coutts, an Ojibwe woman who has been raped on Indian land. After her attacker goes free because of jurisdictional issues on Indian reservations, her teenaged son sets out on a quest to seek justice for his mother, who has retreated to her bed, paralyzed by grief and trauma.

Though the story is fictional, Erdrich’s book accurately captures the terrible toll of rape for Native women

Tribal leaders estimate that the final tally is in the billions for native communities already strapped by poverty and lack of opportunity.

Overlapping Issues

The pervasive and pernicious nature of sexual assault and abuse overlaps with a variety of other serious issues within native communities.

“Sexual assault presents some of the greatest challenges in Indian country,” Kevin Washburn, assistant secretary for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, said in a recent email interview. “Because of the devastating impact that sexual assault can have on self-worth and self-esteem, we know that it may be a contributing factor to the epidemic of youth suicides. As we try to help tribal communities cope with a suicide crisis, it is imperative that we address each of the risk factors. For that reason, we have been working on better responding to the needs of survivors of sexual assault.”

Across the country, geographic isolation and jurisdictional complexities continue to be the biggest obstacles in both the prosecution and restitution of these crimes, particularly in Alaska, which has 229 tribes and is nearly three times larger than Texas.

The Northern Plains and the tribes of the Southwest are similarly situated, with tribal law enforcement and social service departments already bursting with overflowing caseloads and limited resources to prosecute. But with a growing sense of urgency, many tribes are redirecting as many resources as possible to address what is regarded as a human rights crisis in Indian communities.

The two largest tribes–the Cherokee Nation and Navajo Nation, for example–have dedicated agencies to assist their tribal members who are victims of sexual assault and other violent crimes. In 2013, the Cherokee Nation opened the One Fire Victims Service Office, which provides emergency advocate assistance to law enforcement, transitional housing and even legal assistance for victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking or dating violence.

Help Navigating the System

The Navajo Nation Victims Assistance Program also works closely with the three states within its boundaries–Arizona, New Mexico and Utah–to assist its tribal members with help in navigating the legal system, as well as completing applications for financial assistance for health-related expenses, costs of funerals, lost wages, eyewear, and Native healing ceremonies and traditional medicine people.

The smaller tribes, many of whom have poor economies and high unemployment, still struggle with the enormous legal, logistic and financial burdens of sexual assault in their communities.

For them, not much has changed over the years, in spite of new legislation and programs to help stem the violence against Native women.

Gillette recalls a high school friend from the 1980s whose case is one of the few that have ever gone to trial. She says her friend, who was from the Northern Plains, was skewered and portrayed as a “whore” on the stand after being gang-raped by a half-dozen white teenagers from a neighboring community, even though she was a virgin at the time of the assault. Nonetheless, her perpetrators went free while her friend felt punished for coming forward.

“They made an example of her,” said Gillette, who remains haunted by her friend’s case. “The message was clear, ‘This is what’s going to happen to you if you tell.’ And she was only 15 years old. In this day and age, you’d think we’re past that–but we’re not.”

Suzette Brewer is a writer specializing in federal Indian law and social justice issues. A member of the Cherokee Nation, she has written extensively on children and families for Indian Country Today Media Network. Follow her on Twitter @suzette_brewer.