By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

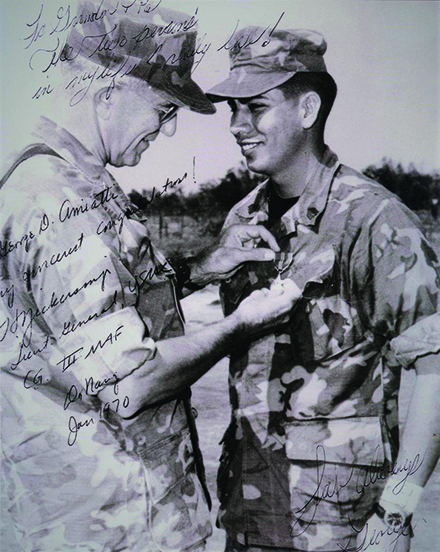

A stunning art exhibit curated by George Amiotte (Oglala Lakota), a decorated United States Marine Corps veteran, recently held its grand opening within the Evergreen State College’s main gallery. Showcasing a wide variety of Indigenous talents and open to the general public through December 30, this exhibit is proudly dedicated to all military veterans, past and present.

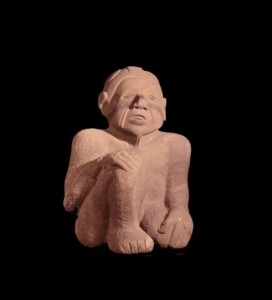

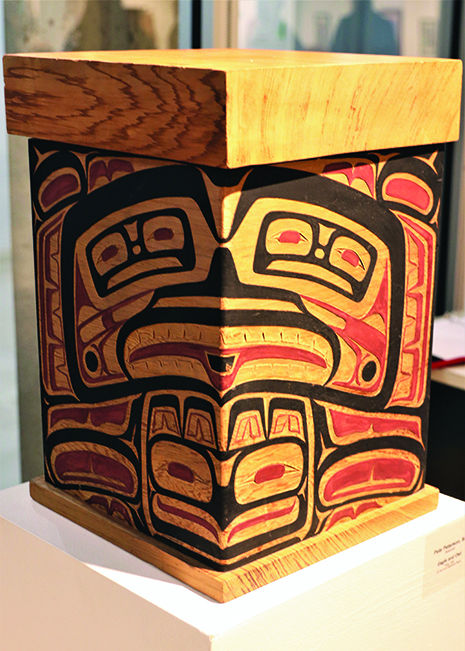

“Art is a living, breathing connection to our ancestors of the past, those living in the present with us, and our future generations. That’s why the title of this exhibit is Past, Present & Future,” explained George while proudly beholding the finished product. “What’s on display here is much more than 2- or 3-dimensional material; there’s a great depth of tradition and shared history told through a method of storytelling that’s been passed on since our people’s beginning.”

“I’ve always had an interest in learning about healing plants, as well as natural materials used in basket weaving. These specific bags on display were made by the mid-Columbia River and Plateau tribes of the Northwest and have always been used for gathering roots, plants, and berries. Because they are a soft bag, they can be folded and stored to be carried from gathering site to gathering site.” – Kathleen

George is a former marine who served two combat tours in the Vietnam War. He’s been immersed in the art realm since returning from Vietnam, from creating art therapy classes in South Dakota for Native children to developing art-based healing workshops that help veterans overcome post-traumatic stress disorder.

“One of my favorite workshops combined mask making and emotional processing that healed the spirit of our traumatized warriors,” recalled George. “You see it’s really hard to take a combat veteran, someone that really experienced the shit, and have them acknowledge what they experienced. By having them create a mask out of wood, clay, or papier mâché that described themselves, similar to a self-portrait, we could then begin to process the emotions and trauma they conveyed through their self-imagery.

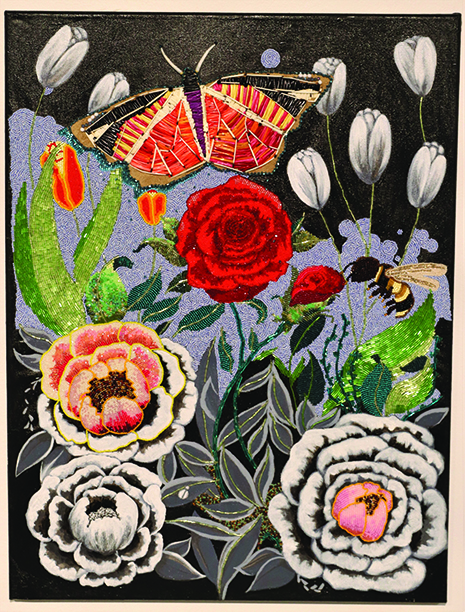

Melinda West.

“The creative process itself acts as therapeutic while giving our warriors a safe place to manifest their emotions because in order for them to heal, they can’t be stripped of their spirit,” he continued. “It’s important for our families and our people to understand that as veterans, we are modern-day warriors, and that warrior spirit has to be respected.”

Through Past, Present & Future, the warrior spirit is respected and showcased as a means to empower Tribes and their vibrant culture during Native American Heritage Month.

The exhibit serves as a powerful educational tool. Through the presence of contemporary Native American art, Evergreen State College transformed its main gallery into an immersive learning space. Students and visitors alike are provided with opportunities to delve into the intricate narratives behind each piece of artwork – stories of creation, spirituality, and resilience. This education raises awareness, dispels stereotypes, and nurtures a deeper understanding of the Indigenous peoples who have called these lands home for millennia.

“I am honored to be invited to share my work with this community of artists,” shared exhibit artist Melinda West. “Born and raised in Seattle, I have lived my whole life on traditional Suquamish Territory. I hope the art I am inspired to make reflects my relationship with the place I live, the plants that grow here, and my respect for Indigenous Peoples living today who are caring for this land as their ancestors have done since time immemorial.

“Since I was a little boy, photographs have intrigued me. Seeing pictures of different cultures and countries is magical. I feel that the importance of documenting Native Americans in the 20th and 21st centuries is of the utmost importance as we continue to protect our sovereignty, our traditions, and our culture. The cultural revitalization of our Nations is tremendous and deserves to be captured and collected via photographs, so that our future generations can look back and be proud of what their ancestors worked so diligently to protect.” – Denny

Evergreen State College is located in Olympia, on the ancestral homelands of the Nisqually people. By implementing another Native-led exhibit, college administrators are furthering their mission to acknowledge the land’s original inhabitants. Incorporating Native American art is both a nod to history and a meaningful way to honor the enduring connection between the land and its Native peoples.

Like the impossible-to-miss welcome figure that stands permanently fixed outside the college’s main entrance, artists of Past, Present & Future strive for their welcomed gallery guests to further their understanding of Native culture, which continues to thrive in the 21st century.