The SAD 54 school board limited remarks to residents of the districts towns and state legislators.

By Doug Harlow, CentralMaine.com

SKOWHEGAN — Whose heritage is honored by the Native American image and the name “Indians” for sports teams?

Is it the players, parents and boosters of Skowhegan Area High School who say the nickname is their tradition, their identity and their way of respecting Native Americans by channeling their strength and bravery in sports competition?

Or does the heritage belong to the native people who lived for centuries along the banks of the Kennebec River, only to be wiped out by disease, war and racism with the arrival of Europeans?

That was the question Monday night during a public forum on the continued use of the word “Indians” as a sports mascot, nickname or good luck charm.

The School Administrative District 54 board agreed to hold the forum, noting that only residents of the school district and state legislators be allowed to speak. The decision drew criticism from those supporting the name change that the gathering would be one-sided, calling it a “mock forum,” but others said it was fair to give residents of SAD 54 their chance to speak out.

Representatives of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Micmac tribes — all members of the umbrella Wabanaki federation in Maine — told a school board subcommittee April 13 that the use of the word Indians is an insult to Native Americans. Members of the four Indian tribes want the name changed. They say they are people and people are not mascots.

The SAD 54 school board will discuss the matter at their regular meeting on Thursday possibly leading to a vote on the issue.

Speakers at the forum appeared to be divided evenly for and against keeping the name. Each speaker was given two minutes to speak.

Harold Bigelow, of Skowhegan, told the assembly of more than 60 people that there are Native Americans “who side with us” in support of keeping Skowhegan the Indians.

“The natives today are being compensated for their past with entitlements and free education,” Bigelow said. “I personally feel they ought to focus on their own problems within, rather than creating problems for others. It is definitely not racist. Do what is right — this is our history, not theirs.”

Mary Stuart, of Canaan, a former SAD 54 teacher, stood to ask with a show of hands how many people in the audience were veterans. She then asked how many had relatives that were veterans. Many more hands were raised.

Stuart then said the people who are veterans get to say they are veterans — not their children and grandchildren — and it’s the same with American Indians.

“I am not a veteran, and we are not Indians,” she said.

School board members said last week that because tribal members had their chance to speak in April, that Monday’s forum was designed to give local people a chance to have their say.

The gymnasium at Skowhegan Area Middle School filled before the meeting with people holding signs saying “Retire the Mascot” and others wearing Skowhegan Indians baseball caps in support of keeping the name.

John Alsop, of Cornville, called for the elimination of the mascot name.

“I contend that if we wish to honor the Indians as we say that we do, we should start first by listening to them,” Alsop said. “If they say they do not want their heritage, their traditions, their culture and identity used as a mascot, then I think we should do as they ask. We should respect their point of view as friends.”

Judy York, of Skowhegan, disagreed, saying she grew up in poverty, just like many other people in the area, including the Native Americans. She said discussion on continued use of the word is all about a name. The school has dropped all of the offensive images of the past, York said.

“We no longer have the images on the shirts, fields or courts, so what is the problem?” York asked. “We have Indians on the brochures for tourism, so what is the difference? It’s who we are.”

Resident Sean Poirier agreed.

“We take pride in our community,” Poirier said. “We will be forever more Skowhegan Indians.”

At issue is not the town seal — an Indian spearing fish on the Kennebec River — or even the image of an Indian painted on the wall of the high school gymnasium, Barry Dana, of Solon, former chief of the Penobscot Nation, has said in the weeks leading up to the forum.

State Rep. Matthew Dana II, who represents the Passamaquoddy tribe in the Legislature, was unable to make Monday night’s forum.

Maliseet Tribal Representative Henry J. Bear was present Monday night and spoke briefly about community spirit and unity, wishing friendship for both sides of a passionate issue. He said after the Revolutionary War the first treaty the new “founders” of the United States made was with the St. John River Indians.

“The first treaty would be signed with the ‘Americans,’” Bear said. “We are the Americans. They were describing tribal people.”

Maulian Smith, a Penobscot woman who grew up and still lives and works on Indian Island, stood to read a letter from Kirk Francis, chief of the Penobscot Indian Nation who authorized her to speak for the tribe. Smith was told that because she is not a resident, she could not speak at the forum as a proxy. A Skowhegan police officer escorted her to her seat, but she would not sit down.

Former Skowhegan selectwoman and county commissioner Lynda Quinn said what the Indian mascot issue has created is fear.

“It’s fear of losing a community identity,” she said. “Fear of being racist. Fear that this is just the beginning of other things that will be forced upon us. Fear of our community being run by and dedicated by people from the outside. Fear begets hate, and hate thrives in political correctness.”

For about 90 minutes people stood to speak of culture and history and respect for what sports boosters grew up loving and honoring and respecting tribal people who say that the word Indian is not respecting them.

Some said it was time to start a new tradition, one based on the actual history of Skowhegan and the Kennebec River. Others said the tradition of Skowhegan Indian pride was here to stay.

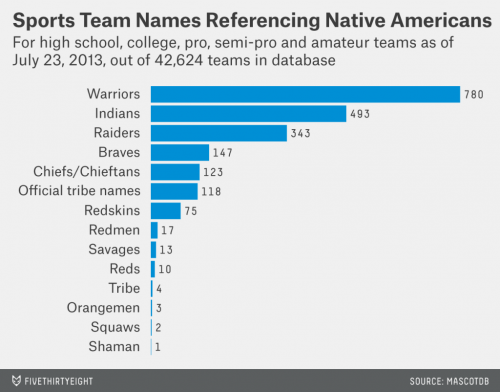

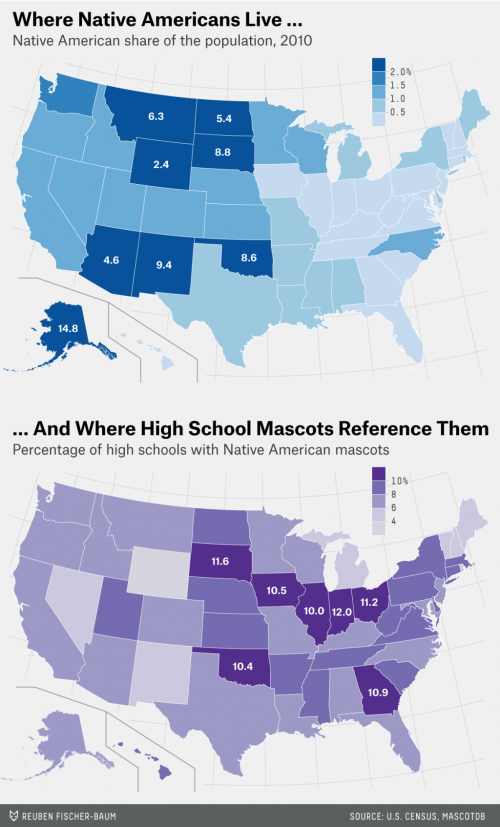

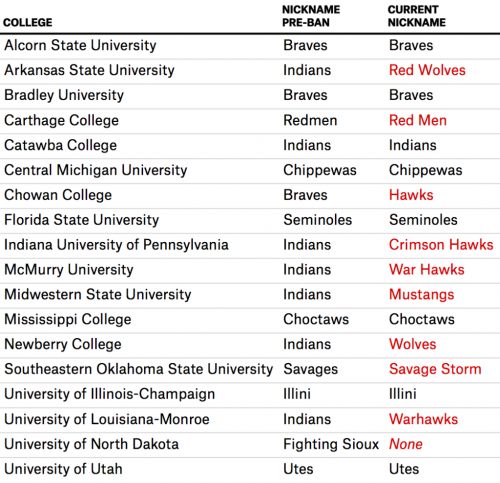

Skowhegan is one of the only high schools left in Maine with an Indian mascot, bucking a national trend to end racial stereotyping of American Indians as sports mascots.

The first Maine school to change was Scarborough High School in 2001. The school dropped Redskins in favor of Red Storm. Husson University eliminated the Braves nickname and became the Eagles. In 2011 Wiscasset High School and Sanford High School eliminated the Redskins nickname. Wiscasset teams are now known as the Wolverines, while Sanford athletes are the Spartans.

In Old Town, the nickname Indians was dropped and Coyotes was adopted.

Greg Potter, superintendent of Newport-based RSU 19, which includes Nokomis Regional High School, said the American Indian image has not been dropped entirely at the high school, but has been incorporated along with other images in a kind of coat of arms to represent the district and its history, not a school sports mascot.

Wells High School has been the “Warriors” also and last year was in the process of phasing out Native American imagery to become a more neutral “Warriors,” according to a published report.

“It’s a process that has been ongoing,” Ellen Schneider, who was Wells superintendent of schools, said in May 2014. “It’s a non-issue in our community. We’re trying to do this quietly.”

Wells Town Manager Jonathan L. Carter on Monday said the Native American imagery appears to be still in place.

“I don’t think they’ve dropped it,” Carter said.

Carter said Schneider has since resigned along with the school district’s business manager, but that he does not know why. Helena Ackerson, chairman of the local school committee; Diana Allen, vice chairman; committee member Jason Vennard and Wells High School principal Jim Daly have not replied to email inquiries for comment on the issue.

Discontent over the Indian mascot is not new for Skowhegan schools.

The school board’s Educational Policy and Program Committee voted in 2001 to keep the Indian name and propose a single American Indian symbol to represent the teams. The SAD 54 board had debated the issue for two years after receiving a letter from the American Indian Movement in 1999. The letter called the use of an Indian for the high school’s mascot offensive.

A committee of high school staff and students in 2001 also surveyed 800 students and staff and found the majority felt that the use of the name “Indians” was not disrespectful, although many of the American Indian symbols, including murals and a wooden sculpture in the cafeteria, did not reflect the tribes from the area.

Another problem was that a mascot head with oversized facial features had been used at athletic events. School board directors banned use of that head after parents complained.