By Mallory Black , Medill News Service

Even with a family military background dating back to World War I, Shenandoah Ellis-Ulmer never considered while growing up that serving in the military might be the right choice for her, too.

But that changed in her sophomore year in college after she was placed on academic probation at the University of Minnesota — what she now says was a much-needed wakeup call to spur her to seek more purpose and direction.

Still unclear, though, was exactly what purpose she should pursue and what direction she should take.

Then she recalled overhearing two classmates in the National Guard talk about the opportunities that had opened up to them after enlisting.

And for Ellis-Ulmer, there was that purpose and direction.

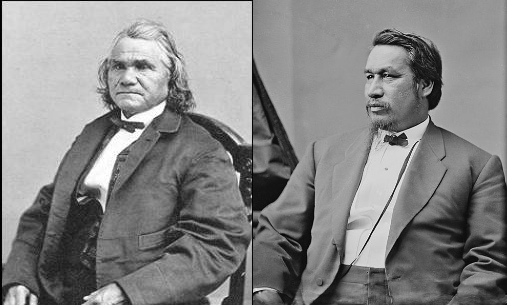

Nearly 20 years later, Air Force Master Sgt. Shenandoah Ellis-Ulmer, now 40, is an intelligence analyst at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington.

She’s also a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation in South Dakota, the first woman in her family to serve in the military and just one of thousands of Native Americans who are serving or have served their country in uniform.

Ellis-Ulmer, who has served in South Korea and the Middle East in addition to her various stateside assignments, said serving in the Air Force “has given my children, my husband and myself a different outlook on the world.”

“I want to give my children a different perspective on life because life is not what the reservation is,” she said. “Life is what you make of it.”

A tradition of service

The Defense Department reports a total of 27,186 American Indian and Alaska Native active-duty officers and reserves, and the Veterans Affairs Department reports more than 156,000 Native American veterans. They have served in every war in American history, and 25 have have received the nation’s highest award for valor, the Medal of Honor.

At least 70 Native American and Alaska Natives have died during combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and 513 others were wounded in those combat zones.

Native Americans traditionally have had a strong military presence because they have a strong sense of patriotism, said Clara Platte, executive director of the Navajo Nation Washington office.

“There’s a deep tie to the land and our people and our culture, and being able to serve in the military is a way to honor that heritage,” Platte said.

But that doesn’t mean the cultural transition from “Indian Country” to military base is always easy.

Army Lt. Col. Tracey Clyde, 47, a member of the Navajo tribe, spent most of his childhood with his grandparents herding sheep near the Sweetwater Chapter on the Navajo Nation reservation in New Mexico.

In high school, Clyde decided to set his sights on attending the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

But once there, he soon realized that adapting to the social norms might be a challenge — even in simple things like the slang cadets might use to greet each other.

“One of the things that I had to keep from getting mad at was when they talk to each other and sometimes say, ‘Hey chief,’ ” Clyde said. “That’s one thing I got mad at my roommate for, but then I noticed other cadets my age were saying the same thing to each other.”

Clyde quickly figured out the greeting wasn’t meant to be derogatory and found his footing as an Army officer. Then while he was stationed in Seoul, South Korea, his Native American culture found him again.

A fellow officer who was also Navajo told him that her baby had just laughed for the first time. Navajos traditionally celebrate a baby’s first laugh, so Clyde and other Native Americans on their base held a ceremony, asking for the baby to be blessed by generosity and kindness.

“All Native Americans — whether they were Navajo or not — met in her apartment and we had our ‘first laugh’ party,” said Clyde, now assigned to the Army Human Resources Command at Fort Knox, Kentucky. “Even though we were far away from our homelands, we still took the opportunity to continue our culture regardless of where we were stationed.”

Throughout his 25 years in uniform, Clyde has taken every opportunity to help other Native Americans adjust to life in the military, so “they’re not so culturally shocked with all the stuff they’re thrown into.”

An honorable life

Ellis-Ulmer, who has deployed 15 times to the Middle East, said that for her, and for most Native Americans, serving in the military is considered an honorable life.

A survivor of childhood sex abuse and domestic violence as an adult, Ellis-Ulmer does her part to help other Native American women who have lived that life.

As a member of the Native American Women Warriors, an all-women color guard that supports Native American female veterans dealing with homelessness, sexual assault trauma and the transition back to civilian life, Ellis-Ulmer regularly speaks at powwows and community events to raise awareness of veteran issues.

“I don’t think I’ve come across one Native woman who has said that they were not abused, whether it was by their husbands, their partners or their family members,” Ellis-Ulmer said. “Dealing with all these violent acts against Native women is my motivation because I don’t want this mentality of abuse to perpetuate.”

As a way to show her appreciation for what the Air Force has done for her, Ellis-Ulmer speaks about military life as part of the We Are All Recruiters program, which allows active-duty members to recruit for the Air Force in their own communities.

Recently the Santee Sioux tribe honored her for her military service with a golden eagle tail feather.

“They told me to wear it turned down,” she explained, “Because now I’m a warrior to them.”