“The Oil Industry’s Sacrifice Zone”

Source: Water4fish

HOQUIAM, WA (6/11/15)– Presenters at a Wednesday night public forum here, which focused on the probable economic and environmental impacts of increased storage and transport of oil in Grays Harbor County, concurred that the results could catastrophic, said Quinault Indian Nation President Fawn Sharp, who added, “the impacts on tribal culture would be beyond measure.”

“Coastal Washington, The Oil Industry’s Sacrifice Zone,” was held at the Little Theater at Hoquiam High School, organized by a coalition of local organizations rallying against the three proposed oil storage facilities at the Port of Grays Harbor and others along the Washington coast. The facilities, proposed by Westway Terminals, Imperium Renewables and U.S. Development, are currently undergoing environmental impact statements under supervision by the state Department of Ecology. Presenters included Ocean Shores Mayor Crystal Dingler, Washington Dungeness Crab Fisherman Association Vice President Larry Thevik and President Sharp. Numerous other local officials attended to demonstrate their opposition to planned oil expansion and the forum was moderated by Eric de Place, of Seattle-based think tank Sightline Institute.

President Sharp pointed out that tribal members have fished and gathered in the Grays Harbor region for hundreds of years and that increased oil traffic will make that more difficult.

“An oil spill would devastate the fish, shellfish and plants that sustain the QIN identity and culture, and would decimate the Grays Harbor economy,” she said.

To achieve a direct and accurate analysis of the potential impacts to Quinault rights and interests, the tribe hired an economist firm, Resource Dimension (RD) of Gig Harbor to do a comprehensive economic analysis of potential impacts the three proposed terminal projects would have on tribal treaty rights and economic interests. RD researched economic data, interviewed several tribal fishers and gatherers, and considered various oil spill scenarios to evaluate economic impacts to QIN from these facilities.

“One thing was clear from the beginning. It is impossible to assign an economic value to the cultural and spiritual aspects of our treaty-protected rights,” said President Sharp. “We will always fight to protect those rights, because they define us as a people. It’s who we are. But measureable economics are also important. In this case, the quantified economics clearly point out the folly of further expanding oil transportation and storage in Grays Harbor County,” she said.

The RD study found that in 2013 668.5 direct jobs were generated by Treaty fishery-based activities and select fishery-related QIN-owned businesses. Purchases made by these entities supported an additional 132.2 induced jobs in the region. The study also found that 107 indirect jobs supported $32.1 million of local purchases made by businesses supplying services to these firms. Direct wages and salaries amounting to $27.6 million were received by the 668.5 directly employed. Re-spending of this income created an additional $5.0 million of income and consumption expenditures in Washington, principally in Grays Harbor County. Those holding induced jobs received $4.3 million in indirect income. Businesses providing services to these firms received $84.7 million of revenues.

Also, in 2013, other QIN businesses contributed 907 jobs, $36.8 million in direct/indirect income, $84.6 million in business revenue, representing $32 million in local spending.

“These figures, which will continue to increase as we invest more in sustainable businesses, training and cooperative efforts with our neighboring communities, clearly demonstrate the profound importance of tourism and a healthy environment in the Grays Harbor area,” said President Sharp.

RD modeled three oil spill scenarios: one on the lower Chehalis River, one in Grays Harbor and one just outside the entrance to Grays Harbor to demonstrate potential economic losses from an oil spill. Among numerous other findings, it was determined that due to minimal containment due to limited spill response capability and tidal and climactic conditions, a spill in Grays Harbor would spread throughout the entire harbor and seaward in a matter of hours. Oil would not be able to be stopped before reaching sensitive areas in the harbor, and the oil would persist. It would kill salmon and other life forms, from the time it spills, for years to come. Shellfish would be particularly vulnerable and acute mortality would be expected. The crab and clam populations in and around Grays Harbor would be devastated, as would the economies based on them. At the minimum, modeled spill scenarios indicate that over the three years of the worst economic impact from a spill, between 105 and 151 tribal fishing jobs would be reduced. Tribal fishing incomes would be slashed from between $12.8 million and $17.1 million, and overall fishing incomes could reduce from between $24 million to $40 million.

Impacts to QIN businesses, such as the hotels, casino and QMARTS over a three-year period following a major spill could result in a loss of 118 to 229 jobs, along with personal income losses of $14.7 million to $28 million, QIN business losses of $29million to $70 million, and local purchasing losses of $10.3 million to $23.4 million.

“It’s important to remember that these are non-Indian as well as Indian jobs, and that ultimately the oil industry proposals result in just a handful of jobs. How much clearer can this decision be? The risk the oil industry is asking us to take is not worth it,” said President Sharp.

De Place first talked about the large number of proposed and active oil storage sites that have popped up in the Pacific Northwest since 2012, saying the amount of carbon in those projects is roughly equivalent to five and half Keystone XL Pipelines. He estimated the three terminals would result in 300 to 400 additional loaded oil vessels per year taking loaded crude oil out of the Harbor, with about 800 to 900 extra oil trains annually, or two and a half to three dangerous oil trains coming through Grays Harbor daily. He said the federally estimated cost to recover from a worst-case scenario derailment is about $5 billion, or at least ten times the amount of insurance most railways carry.

“If there were an accident, the local community would be left to pick up the tab,” he said.

Thevik, a commercial fisherman for 45 years, said the oil proposals could have severely damaging effects on the Grays Harbor economy. He cited a recent report that said more than 2,000 jobs and more than $200 million in revenue come from commercial fishing activity in Westport, adding that a National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration study stated 67,000 jobs in Washington State were based on seafood-related activity. In Grays Harbor County 31 percent of the local workforce depends on marine resources. Yet the oil that would move through proposed Grays Harbor and Vancouver sites would equal half of the oil moved by rail throughout the entire country in 2014. He noted that the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 spilled 11 million gallons of oil, affecting 1,300 miles of Alaskan coastline. On Grays Harbor, proposed oil transport would see tankers carrying upwards of 15 million gallons each.

“Our members have witnessed first-hand the difficult task of recovery of oil on water and on shorelines. Many have also witnessed the promise to pay for damages and the reality of payment,” he said, adding that Exxon was appealing judgments for payment 19 years after the Alaska spill. A quarter of a century later, the company still owed $92 million and much of the oil is still there, the cleanup job apparently long since abandoned.

Dingler talked about the “Nestucca” oil spill that occurred in 1988 on the Washington coast. She, too, talked of the severe economic effects a spill would have on the region’s economically.

“Ocean Shores is known for our beach,” she said, adding “oil spills can easily change that.”

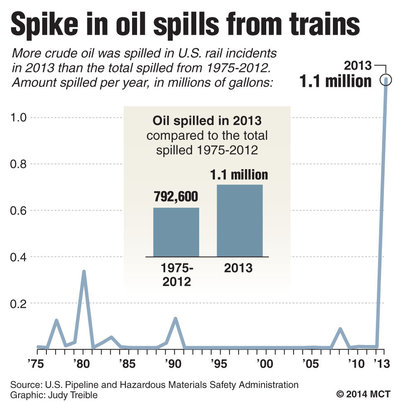

But until just a few years ago, railroads weren’t carrying crude oil in 80- to 100-car trains. In eight of the years between 1975 and 2009, railroads reported no spills of crude oil. In five of those years, they reported spills of one gallon or less.

But until just a few years ago, railroads weren’t carrying crude oil in 80- to 100-car trains. In eight of the years between 1975 and 2009, railroads reported no spills of crude oil. In five of those years, they reported spills of one gallon or less.