Photo courtesy of Joe Seymour

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News Photo courtesy of Joe Seymour

Recently, the Seattle Art Museum presented PechaKucha Seattle volume 63, titled “Indigenous Futures.” PechaKuchas are informal and fun gatherings where creative people get together and present their ideas, works, thoughts – just about anything, really – in fun, relaxed spaces that foster an environment of learning and understanding. It would be easy to think PechaKuchas are all about the presenters and their presentation, but there is something deeper and a more important subtext to each of these events. They are all about togetherness, about coming together as a community to reveal and celebrate the richness and dimension contained within each one of us. They are about fostering a community through encouragement, friendship and celebration.

The origins of PechaKucha Nights stem from Tokyo, Japan and have since gone global; they are now happening in over 700 cities around the world. What made PechaKucha Night Seattle volume 63 so special was that it was comprised of all Native artists, writers, producers, performers, and activists presenting on their areas of expertise and exploring the realm of Native ingenuity in all its forms, hence the name Indigenous Futures.

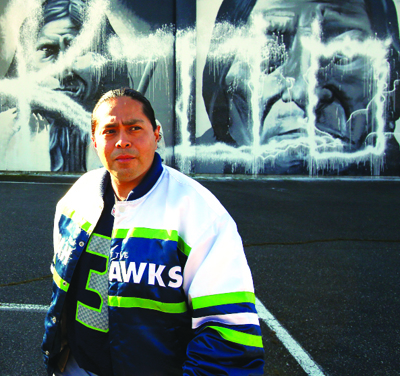

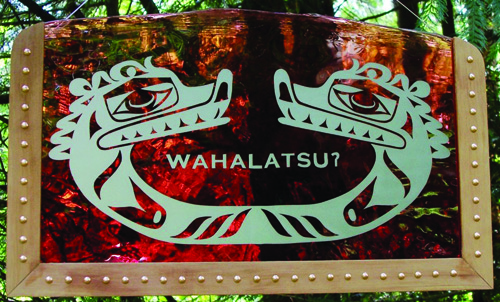

Joe Seymour, a member of the Squaxin Island Tribe, is geoduck harvester and a leader of his canoe family, but most importantly he is a Coast Salish artist who works with a vast array of mediums. He has demonstrated his artistic touch with blown glass, etched glass, prints, wood, Salish wool weaving, canvas and traditional rawhide drums. His ancestral name, wahalatsu?, was given to him by his family in 2003. Wahalatsu? was the name of his great-grandfather William Bagley.

Photo courtesy of Joe Seymour

Seymour started his artistic career by carving his first paddle for the 2003 Tribal Journey to Tulalip. Also, in 2003, he carved his first bentwood box. After the Tulalip journey, he really began to focus on his artistic abilities he found were coming so natural him. After learning how to stretch and make traditional rawhide drums, Seymour pushed his creative limits even further by learning how to pull a four-sided drum. The inspiration for learning the four-sided drum method came from his uncle Phil and the late Makah hereditary chief, Lester Hamilton Greene.

“One of the reasons I wanted to work with so many mediums is that all of them together encompass what Coast Salish culture is to me,” explains Seymour of his diversity of art mediums. “We talk about indigenous futures and right now I’m focused on taking the Coast Salish culture into the future by keeping its past alive. I do this by bringing it into the modern world by my weaving, by my drawing, by my painting…I do that with the paddles that I carve.

There aren’t many people who can pull a four-sided drum. I’ve only seen maybe three other people who can do it. If you ever want to learn or know someone who wants to learn, please let me know as I’m more than willing to share our cultural knowledge. Artistic methods are a critical part of our culture and I believe they should be shared willingly, not just held hostage by any single individual.”

Since discovering his inner artist by way of the 2003 Tribal Journey to Tulalip, Seymour has gone on to participate in the international gathering of Indigenous Artists, PIKO 2007, in Hawaii, and he also participated in the Te Tihi, 4th Gathering of Indigenous Visual Artists, in Rotorua, New Zealand, in 2010.

“It’s an honor to have the opportunities to travel the world and meet fellow indigenous; to see and share our cultures via artistic expression,” says Seymour. “The indigenous future of the peoples in the Pacific Northwest is very bright. We have such a wonderful array of spirit, tradition, and pride.

In my career, I’ve worked with glass, photography, Salish wool weaving, prints, wood, and rawhide drums. I’ve been very fortunate to have a community of artists that I’m able to work with and who are very supportive of my career. If it were not for their caring and sharing of ideas, I would not be the artist that I am today. I hope that as I continue in my artistic career, I can pass on the teachings and nurturing spirit that have been shown to me.”

Photo courtesy of Joe Seymour