By Walter Lamar, Indian Country Today Media Network

What does it say about safety in Indian country when a television plot featuring meth distribution incorporates tribal land? Breaking Bad might give Indian country the new name of “Broken and Bad” after the brutal television series, featuring tribal lands, exemplified a continuing public safety crisis. Season 5, Episode 13, entitled “To’hajiilee,” aired on September 8, 2013 and marks the beginning of the end for the wildly popular AMC series. It’s also one more example of how the media persistently depicts Indian country as the place to go to commit drug crimes, murder, and general mayhem.

From the very first episode, and periodically throughout the series, the remote To’hajiilee lands have been the setting for drug manufacture, murders, and concealing evidence. To’hajiilee is a non-contiguous section of the Navajo Nation lying in parts of three New Mexico counties, about 32 miles west of Albuquerque. Despite its proximity to an urban area, To’hajiilee feels isolated and remote. A tangle of secondary roads, many both unmarked and unpaved, crisscross the reservation’s 121 square miles. With only 2000 residents, you may go miles without seeing a soul. In “Breaking Bad,” the series of crimes committed on these tribal lands (theft, murder, extortion, drug manufacture and distribution, assault and much else), set the stage for what promises to be a violent and action-packed series finale.

To’hajiilee is not so different from tribal lands across the nation. All this got me to thinking, “What if the crime depicted in Episode 13 had really happened?” The To’hajiilee reservation is in trust status, which means concurrent federal and Navajo Nation criminal jurisdiction. Federal statute and Navajo Nation codes, ordinances and statutes govern the activities of visitors and residents. But wait, it’s not that easy. Indian Country is the only place in the world where jurisdiction is dependent on race. When a crime is committed within the exterior boundaries of the reservation, law enforcement has to determine if the perpetrator is American Indian, if the American Indian perpetrator is an enrolled tribal member of a federally recognized tribe, whether a tribal or federal statute is being violated, whether the land is indeed trust land, and whether officers responding to a crime are properly certified or deputized.

With that in mind, back to how the To’hajiilee showdown might play out in reality. White supremacists show up with fully automatic weapons (non-Natives to be sure), called by drug kingpin Walter White (another non-Native) when approached by two armed DEA agents and their informant. Everyone knows that $80 million in cash is buried in plastic barrels at the site. Predictably, the shooting starts. Some folks are wounded, some killed. Let’s say one of the wounded tries to make a panic-stricken call to 911. Too bad there’s not good cell phone coverage on the rez— he is out of luck. But wait, some distance away, a Navajo family hears the SUVs rumbling by, followed by a barrage of gunfire, and one heroically drives to a spot of known cell coverage and calls 911. The 911 call gets routed to a surrounding country dispatch, who places a telephone call to Navajo Police dispatch at Crownpoint, New Mexico.

Only about 300 officers patrol the Navajo Nation, which covers a territory larger than many US states. The tribal government has been active in stepping up law enforcement activity under the Tribal Law and Order Act, but cuts in funding have prevented the tribe from hiring anywhere close to the level they need- estimated to be about 800 officers. A couple of officers are on duty at the To’hajiilee substation when the call comes in, and one of them responds by driving to meet the family who called. They direct him toward the area where they heard the gunshots.

The brave officer approaches the scene and finds himself seriously outgunned. When fired upon, he retreats and finds that he doesn’t have radio coverage to call for help, so he drives until he gets a signal so he can communicate he has been fired upon and that there are multiple armed subjects. At best, there are two other Navajo Nation officers on duty at To’hajiilee and back up is 118 miles away in Crownpoint. Back at the substation, they call in to the FBI and the BIA, 32 miles away in Albuquerque. They think about calling in the State Patrol (“Wait, is there a cross-deputation agreement in place? Who could we ask?”). Then they realize, “Whoa, is the incident for certain on our land? Isn’t that near the boundary with Laguna Pueblo? Do we call them, too?”

Meanwhile, the white supremacists kill everybody, grab the money and head out. After no shooting for a period of time, the Navajo officer cautiously approaches the crime scene fraught with death and destruction, over an hour after gunshots are first heard. Later, the FBI and BIA arrive on scene. They realize two DEA agents are among the dead. The FBI and DEA immediately engage in a turf battle as to primary jurisdiction. BIA is caught in the middle and the tribal police are left out. Another twist comes when US Attorney’s office decides where and how survivors are going to be prosecuted, a result of Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, a 1978 United States Supreme Court case wherein the court found that non-Indians are not subject to tribal jurisdiction.

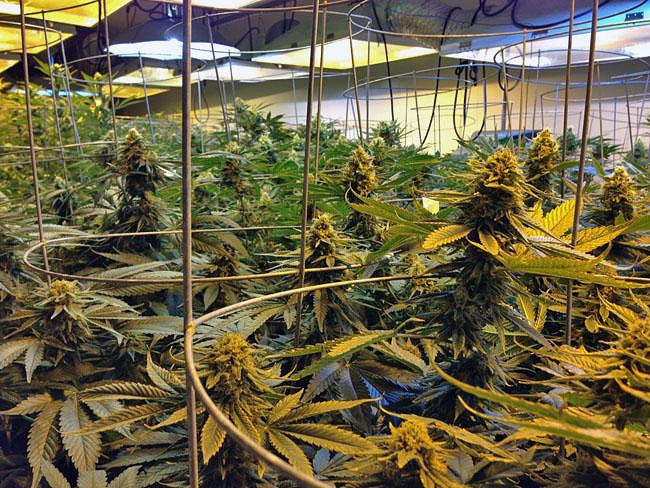

Sure, television is fanciful, but it’s true that criminals have found that doing business in Indian country is profitable because of the remoteness, the lack of officers on patrol, and the jurisdictional tangles created by non-Indian crime on Indian land. Tribes struggle constantly with violent crime and drug trafficking committed by non-tribal members. Meth certainly is a problem on the Navajo Nation and elsewhere in Indian Country; Native Americans are more than twice as likely to abuse this terrible drug.

The effects of meth on people and the environment are truly horrific and would require another article to describe. Methamphetamine use affects the user’s physical health, mental health and emotional stability. The production creates toxic fumes and chemicals, as well as explosive gases, and abatement can require residential demolition. Children exposed to meth either in utero or in the home can develop neurological, cognitive, developmental and behavioral problems.

The Navajo Nation actually has a zero-tolerance policy toward methamphetamine sales, and in the past, the Navajo Nation Division of Public Safety has successfully collaborated with the Drug & Gang Unit, the FBI, the BIA, the Flagstaff police and even the Phoenix police to investigate, arrest and prosecute meth distributors, resulting in entire rings being busted up.

There hasn’t been a high-profile arrest in years, but it’s not necessarily because there are fewer people manufacturing, smuggling or selling drugs on our tribal lands. Just as with tribes across the country, the Navajo Nation police, courts and corrections have been hit hard by the double whammy of planned budget cuts and an across-the-board sequester. The Navajo Nation Department of Corrections has completed two new jails, built as part of the TLOA promise, but the department faces a shortfall in completing the remaining five, or even staffing the new ones. Law enforcement is staffed at less than half of recommended levels. Criminal investigators routinely cover 600 or 700 miles a day to accomplish a single task. The 19 lawyers in the US Attorney’s office dedicated to prosecuting crime are too few to cope with the volume of cases, and end up declining to prosecute about half the time.

Everyone is frustrated by their inability to curb the violent drug crimes that are occurring in their jurisdictions. Officers at Fort Peck, another large reservation, know about drug smuggling from Canada, but often can’t respond in time when planes touch down on remote airstrips. Tribal law enforcement from New York to California know about gang or cartel members who seduce Native women, who protect them (and abet them) as they distribute drugs in the jurisdictional limbo of Indian Country.

How do cartels know that Indian country is the best place to commit crimes? To come around full circle, we can thank the media, from NPR to the New York Times, for sensationalist coverage about reservation crime. Breathless coverage of a Mexican drug trafficking organization on the Wind River Reservation, who exploited Native women to move meth, spurred copycat cases across the country. Evidence collected in one cartel bust actually yielded a Denver Post article discussing how hard it is for drug dealers to get busted in Indian country.

What can be done? The fact is that meth use is ever so slowly lessening its grip on our people, and part of the change is coming from community members. Events like Meth éí Dooda Awareness Day involve everyone in the community from small children to grandparents, and from people in recovery to representatives of the tribal government. In the case of tribal communities like To’hajiilee, outreach to citizens on the best information to give to 911 for a speedy response would also help. Community awareness is the first step in community policing, but there has to be actual policing as well, and that’s where the stumbling block remains.

To effectively police the lands under their jurisdiction, tribal police need resources, and they just don’t have them now. The Tribal Law and Order Act, if fully funded, would enable tribal police departments to patrol remote territory, to negotiate shared resources with state and county agencies, to engage in outreach to endangered youth, and to staff tribal courts and tribal prosecutors’ offices. Congress is back in session this month and we need to put pressure on them to address this problem by fully funding TLOA.

This week, To’hajiilee made the news again as catastrophic flooding hit the Navajo Nation and took out a chunk of the Interstate through the To’hajiilee lands, in the midst of evacuations in many communities, and alarm about the dam failing. The Navajo first responders worked smoothly with each other and with state police and tribal agencies to rescue, evacuate, direct traffic and keep the dam from breaching. Our Native law enforcement officers have proved that they can meet the challenge of To’hajiilee’s real-life crisis. The question remains whether Congress can meet the challenge of keeping their promise to our tribal police.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/09/29/breaking-bad-or-already-broken-drug-crime-rez-all-too-real-151493