Ravalli comments leave tribal elders thinking of the past

Missoula Independent

by Jessica Mayrer December 5, 2013

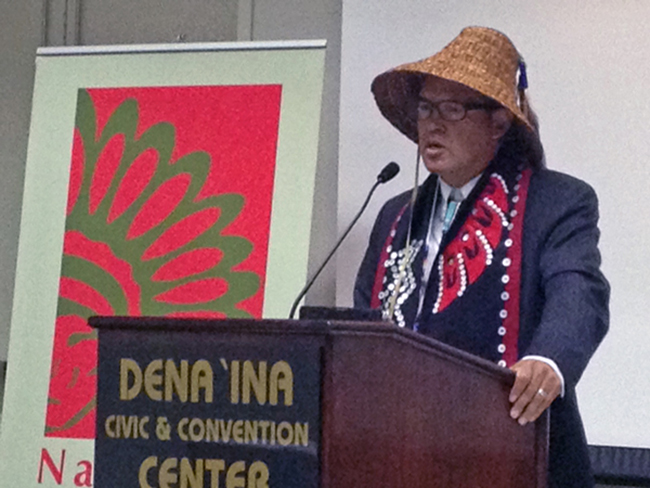

Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribal elder Tony Incashola Sr. says that despite experiencing racism from the time he was a child growing up in the 1950s on the Flathead Indian Reservation, he couldn’t help feeling surprised by a Ravalli County official’s portrayal of American Indians during a public meeting last month as drunken lawbreakers.

“I guess I shouldn’t be,” Incashola, 67, says. “I’ve lived with that all of my life … When I was a kid, it was like standing at a department store on the outside looking in. You see the non-Indian children having fun. You felt like an outsider, that you weren’t welcome, because you didn’t dress right and you had a different color.”

Incashola, who serves as director of the Salish-Pend d’Orielle Culture Committee, has dedicated much of his life to fostering an understanding of indigenous ways. Education breeds familiarity, he says. Familiarity helps break down the fear that breeds racism. Efforts such as his are paying off. Incashola says that racism is less apparent than when he was young. That makes the Nov. 20 meeting in Ravalli County all the more troubling.

The meeting involved a discussion between CSKT delegates and the Ravalli County Board of Commissioners about how best to care for a historic Bitterroot Valley property known as Medicine Tree that the Salish have considered sacred for hundreds of years. CSKT wants to transfer the property from tribal ownership into federal trust with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. CSKT representatives stated that the 58-acre parcel is central to Salish creation stories, ones that detail how “Coyote,” a being imbued by the creator with special powers, made the land “safe for humans yet to come,” Incashola says.

!["Ravalli]()

When explaining the importance of such a transfer, the CSKT say that the Medicine Tree parcel provides a connection to indigenous history—a link that helps preserve a strong sense of tribal identity. The CSKT add that the transaction will help grow their land base and, therefore, give them a more powerful voice when negotiating their rights and responsibilities with government agencies.

CSKT attorney Teresa Wall-McDonald told the Independent that placing land into trust helps the tribes gain back losses accrued when the federal government opened the Flathead Reservation to non-native homesteaders in 1910. Between 2009 and August 2013 alone, the CSKT placed approximately 81,000 acres into trust.

“Part of the process of restoring our homeland includes restoring the land,” Wall-McDonald says. “It is part of rebuilding our homeland, what I call nation building.”

The Ravalli County Commission, however, has steadily opposed the CSKT’s request. Among the commissioners’ stated concerns is the loss of roughly $800 in property taxes that would result from the transfer. They also worry about the potential impacts of having a pocket of sovereign land set aside within their county, and why the tribes would want to work with the federal government rather than local. At the Nov. 20 meeting, they asked specifically if the tribes intended to erect a casino atop the parcel.

Later during the same meeting, Ravalli County Planning Board Chair Jan Wisniewski warned commissioners of the CSKT’s request, saying that American Indians have a history of using trust lands as a refuge to “get drunk and try and run back into the reservation so they don’t get caught,” according to meeting minutes.

“The county cannot go into that sovereign nation to apprehend the drunken Indians,” he said. “So the jails are full of Indians (sic) which cost us tax dollars. One jail in particular (Havre?) had a count of 58.”

In response to Wisniewski’s testimony and the behavior of the Ravalli County officials, Bitterrooter Pam Small posted an online petition demanding that the commission apologize for the county’s “cultural insensitivity and ignorance” that garnered nearly 500 signatures.

Such criticism helped persuade the commissioners on Nov. 27 to issue an apology to the tribes. Roughly 20 Bitterroot residents attended the meeting, with many of them verbally lashing out at the commissioners, characterizing the county’s overall treatment of the CSKT as “paternalistic” and akin to “an inquisition.”

“The whole tone of this meeting was confrontational,” former Ravalli County attorney George Corn said. “They were grilled by your attorneys … At best it was denigrating. At worst, it implied racism.”

In response to the onslaught, county commissioners say that the Nov. 20 discussion was taken out of context—that they were only attempting to evaluate all possible outcomes that could result from the transfer. “It was in no way condescending or adversarial,” Commissioner Jeff Burrows said last week, before the commission voted to hand-deliver an apology to the tribes.

Wisniewski’s legal advisor, Robert C. Myers, echoes the commissioners when maintaining that his client’s statements were taken out of context. “We don’t know yet fully what was actually said,” he says. “People hear what they think they hear.”

For Incashola, the issue comes back to education and respect. For instance, he says the thought of the tribes placing a casino on Medicine Tree is preposterous and reflects a misunderstanding of the importance the CSKT place on preserving their culture.

“I think the county commissioners don’t understand,” Incashola says.

The whole back and forth leaves him weary.

“I get so tired of trying to defend my identity, to try to defend my values,” he says. “I feel that what happened in Hamilton is just plain ignorant.”

Incashola says his elders, who faced the worst kind of racism, taught him that there are more good people in the world than bad. He takes some comfort in that thought. In light of what transpired in Ravalli County, however, Incashola isn’t confident that racism will ever completely disappear.