CREDIT: Rick Vetter

Wynne Parry, LiveScience Senior Writer

Date: 27 April 2011 Time: 03:24 PM ET

Climate change may give America’s venomous brown recluse spiders a choice: Move to a more northern state or face dramatic losses in range and possible extinction, a new theoretical study suggests.

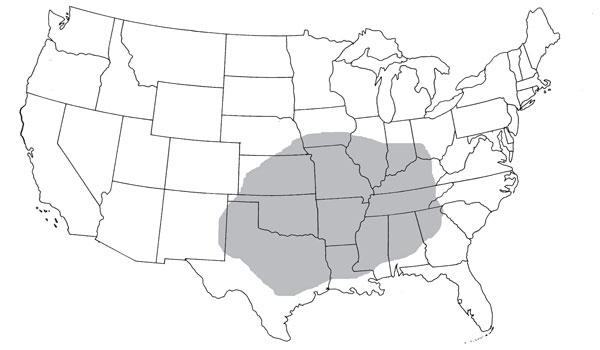

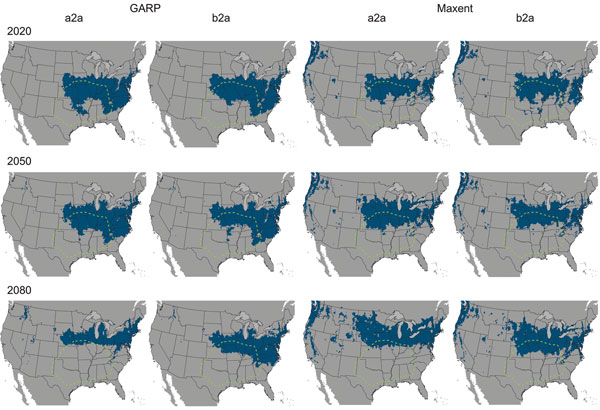

Currently, brown recluse spiders are found in the interior of roughly the southeastern quarter of the continental United States. Researcher Erin Saupe used two ecological computer models to predict the extent of the spider’s range in 2020, 2050 and 2080 given theeffects of global warming.

“The actual amount of suitable habitat of the brown recluse doesn’t change dramatically in the future time slices, but what is changing is where that area is located,” said Saupe, who was pursuing a master’s degree at the University of Kansas when she did the work. She is now a doctoral student there.

If the projections are correct, by 2080, perhaps only 5 percent of the spider’s current range — which extends from Kansas across to Kentucky and from Texas across to Georgia, including the states in between — would remain suitable for it. However, climate change could make portions of Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Nebraska and South Dakota habitable to the spiders.

CREDIT: Erin Saupe/PLoS ONE

Arachnophobia

This may come as a surprise to some residents of these states. In many minds, brown recluse spiders – with their outsized reputation for bringing death, amputations and paralysis – already occupy most of the country, Rick Vetter, a research associate at the University of California, Riverside contends.

Vetter, one of the study authors, created the Brown Recluse Challenge, a 4½-year project. “I got tired of people telling me that brown recluses are all over the U.S and Canada, and I said, ‘Send them to me and I will identify them,'” Vetter said.

One thousand, seven hundred and seventy three spiders later, it was clear that any brown, eight-legged arachnid was at risk of misidentification as a brown recluse – 79 percent of the specimens he received from people across the country were not of the species Loxosceles reclusa, Vetter told LiveScience.

“People fear the unknown. … They like to tell scary stories, they are willing to believe bad things about things they don’t like anyway, so there is a lot of human psychology that is wrapped around the brown recluse,” he said. [Top 10 Phobias]

The challenge has since been picked up by the University of Florida.

In nature, brown recluses live underneath bark or logs in dry areas or underneath hanging rocks. But humans also create a good habitat for them in cellars, attics and garages, according to Vetter.

Their venom contains a toxin that causes skin to die, resulting in what are known as necrotic lesions. In about 90 percent of cases, the bite of a brown recluse has virtually no effect. The other 10 percent cause severe symptoms with potentially life-threatening complications. There are no solid statistics available, but Vetter estimates that one or two bite-induced deaths occur each year, typically in small children.

Homebody spiders

In spite of their affinity for human-created habitats, these spiders have little success establishing and spreading outside their native range. They may be transported when people move outside the spider’s native range, and they can infest a new house, but they won’t spread from there, Vetter said.

“Think about the Dust Bowl era,” he said. “How many thousands of people came to California, how many tens of thousands of boxes of possessions they brought with them, and how many hundreds of thousands of brown recluses came with them? And they didn’t establish a population in California.”

Brown recluses cannot travel on air currents, unlike some other spiders, which limits their means for transport. [How Spiders Fly Hundreds of Miles]

It is possible the spiders may be unable to move north quickly enough to establish in new habitat as parts of their current range become inhospitable, although it is conceivable that by hitching a ride with humans, the spiders may make the migration, the researchers write in a study published online March 25 in the journal PLoS ONE.

The study used two greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, one more dramatic than the other, derived from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The two modeling programs took seven environmental variables related to temperature and precipitation into account.

Both of the emissions scenarios indicated new states could be invaded as far north as parts of Minnesota, Michigan and South Dakota. Both scenarios were run using the two ecological models, resulting in divergent trends. One model showed that the spiders’ habitable area would decrease with time, while the other showed an increase in habitable area.

The predictions should not be taken as gospel; the models aren’t perfect. Saupe used them to predict the current range of the brown recluse and found that it included the Atlantic coast states, farther east than where the spiders actually are. The discrepancy may be due to an error in the model, or it may be that spiders are being kept from the habitable territory closer to the coast by a barrier, perhaps the Appalachian Mountains, Saupe said.

Of course, brown recluse spiders aren’t the only living thingswhose habitat is affected by climate change.

“It is scary to think that if this much change could happen in one species, what could happen in the myriad species that exist all over the Earth?” Saupe said.

CREDIT: Erin Saupe/PLoS ONE

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and onFacebook.