The Cascadia fault in the Pacific Northwest is locked up, meaning that a massive megathrust earthquake could occur at any time, seismologists are warning.

“It’s impossible to know exactly when the next Cascadia earthquake will occur,” said Evelyn Roeloffs of the U.S. Geological Survey, speaking last year on the 313th anniversary of a massive quake that hit in 1700—the last major one in the region. “We can’t be sure that it won’t be tomorrow, and we shouldn’t make the mistake of assuming we have decades to prepare.”

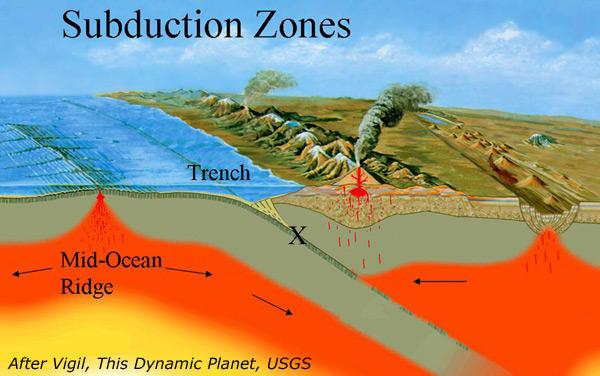

The tectonic plates normally glide and rub against each other, but periodically they become wedged together. When the fault quits sliding and becomes “locked” in place, it builds energy until it finally ruptures, relieving hundreds or thousands of years of stored-up stress in seconds, Roeloff said.

Now, earthquake scientists from Canada and the U.S. who monitor seismic activity along the Cascadia coast have concluded that the dangerous fault line is fully locked, which carries serious implications for an earthquake in the Pacific Northwest.

“What is extraordinary is that all of Cascadia is quiet,” University of Oregon geophysics professor Doug Toomey told the Associated Press earlier this month.

Research on the Cascadia Subduction Zone in 2012 and 2013 led researchers to similar conclusions.

A big unknown, Toomey told AP, is how much strain has accumulated since the plate boundary seized up, and how much more strain can build up before the fault rips and unleashes a possible magnitude 9.0 megaquake and tsunami.

“If there were low levels of offshore seismicity, then we could say some strain is being released by the smaller events,” Toomey told AP. “If it is completely locked, it means it is increasingly storing energy, and that has to be released at some point.”

Toomey said he is “very concerned” and said it is imperative that people in the Northwest continue to prepare for a big earthquake.

Cascadia’s Subduction Zone is a very long, very dangerous undersea fault that divides the Juan de Fuca oceanic and the North America continental plates. It runs from British Columbia down through Washington and Oregon and into northern California, as does a volcanic mountain range.

The fault has produced at least seven magnitude 9.0 or greater megathrust earthquakes in the past 3,500 years, a frequency that indicates a return time of 300 to 600 years.

The massive earthquake on the night of January 26, 1700, was one of the world’s largest. The Cascadia fault ruptured along a 680-mile stretch, from the middle of Vancouver Island to northern California, producing tremendous shaking and a huge tsunami that swept across the Pacific.

The oral history of the Makah Tribe in Washington tells of a huge earthquake that happened in the middle of the night long ago. Those who had heeded their elder’s advice to run for high ground survived. After spending a cold night in the hills with animals that also had fled the rushing waters, the survivors found that their village, along with neighboring coastal villages, had completely washed away, leaving no survivors.

RELATED: Traditional Knowledge Informs of Japan-Style Earthquake Danger Off U.S., Canada

Today it’s quite common to see cars backed into parking spaces in the tribal coastal villages in Washington so that in the event of a tsunami warning, drivers can make a fast getaway to higher ground. And at least one tribe, the Quileute Nation, is moving its coastal village away from the tsunami danger zone.

RELATED: Quileute Is Moving to Higher Ground

An emergency kit and plan are important first steps in being prepared. Download the Red Cross Earthquake Safety Checklist to learn more. Those with smart phones can text “GETQUAKE” to 90999 or search “Red Cross Earthquake” for their mobile app in the Apple App Store for iPhones or Google Play for Android.

RELATED: Haida Gwaii Quake Brings Home the Importance of Quileute Relocation Legislation

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/12/16/cascadias-locked-fault-means-massive-earthquake-due-pacific-northwest-seismologists