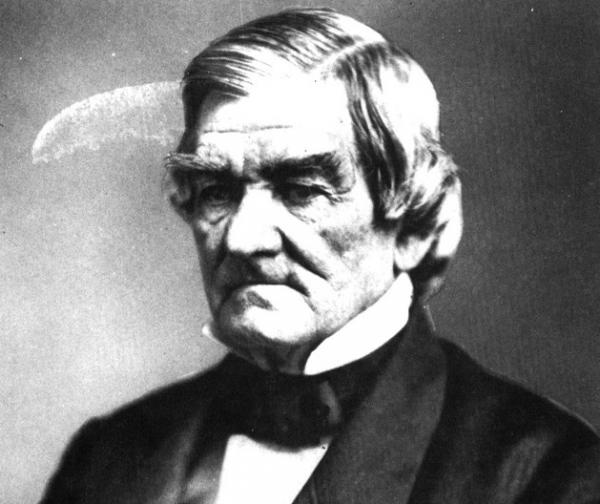

Wikimedia Commons

John Ross served as Cherokee Principal Chief from 1828 to 1866.

By Duane Champagne, Indian Country Today Media Network

Many traditional American Indian governments have significant organizational similarities with contemporary parliamentary governments around the world. A key similarity is that leadership serves only as long as there is supporting political consensus or confidence that the leader or leadership represents the position of the community or nation. Generally, indigenous political leadership serves at the consent and support of the local group, community, or nation.

Leaders, or speakers, express a consensus position among community members. In negotiations or actions, the leader has power to act only if the leader carries out the wishes of the constituent community. Indian nations usually have local, regional, and national leaders, where political processes and sustained leadership depends on consent among tribal members. While an Indian leader has the general consensual support of the community or region they represent, the leader remains in office. When the leader upholds the desired goals and interests of the represented community in political action, community members are supportive of leadership.

If, however, a leader acts against the community consensus, the community withdraws political support. If a leader is in a hereditary leadership position, the hereditary leaders influence is lessened, as community members will follow other leaders who are willing and able to represent tribal needs, interests and desires.

There are multiple historical examples of such leadership patterns in many Indian nations. John Ross, Cherokee Principal Chief from 1828 to 1866, represented the majority of Cherokee citizens, most of whom had traditional economic orientations, while often taking up Christian religion and were committed to the Cherokee constitution and nation. Ross was a slaveholder, Methodist, but at the same time was an avid politician whose support could not completely rely on the minority mixed blood slave owner class. Ross as leader represented the interests of the majority of Cherokee, and if he had not done so they would have removed him from office and elected a more accommodating Principal Chief.

Another example is the removal of Haudenasaunee Chiefs by clan mothers, if the chief was warned three times he was not properly representing the views of the clan or nation.

In contemporary parliamentary governments when parliament is dissatisfied with the ruling leader and its party, action is taken to remove leadership. If the leader does not have the majority confidence of the parliament, the leader has to call for elections to reconsider new leadership. Most contemporary American Indian constitutional governments have elections that are similar to the U.S. constitution.

Elected officials serve in office for specified terms, whether or not they have the support of the community or nation. As American Indians are within the U.S. sphere of influence, American political models are predominant. Indian leaders, often in Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) governments, can control the government with a majority vote within the tribal council. If the leaders do not represent the interests of the community, tribal members must wait until the next election to remove them from office.

Unlike non-Indian parliamentary governments, which are organized by political parties, American Indian communities still are often organized by confederations of kinship groups, villages, or band localities. The families, clans, and villages are active social and political entities, and continue to observe traditional political processes and recognize and uphold leaders who serve community interests.

Many tribes that rejected adopting U.S. style constitutional governments retain a form of consensus-based political relations built upon traditional kinship and locality arrangements that is usually unique to their nation. Many traditional tribes saw constitutional governments as too inflexible, perhaps because leadership patterns, especially in IRA governments, were not directly responsive to tribal community pressures and interests. Community political consensus was a primary check and balance that communities put on tribal leaders so they served community needs. It is never too late for tribal communities to rethink their constitutional forms and make them more compatible with consensually-based traditional or parliamentary government patterns.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/09/27/how-does-tribal-leadership-compare-parliamentary-leadership-151377