ON THE TREATY FRONT: A new monthly series on the history and meaning of tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, environmental stewardship and issues that threaten these important rights. This is just the first in a recurring series of articles produced by the Tulalip Tribes Treaty Rights Office to help educate and inform the membership. Our Mission is to “Protect, enhance, restore and ensure access to the natural resources necessary for Tulalip Tribal Members’ long-term exercise of our treaty-reserved rights.”

Submitted by Ryan Miller, Tulalip Tribal Member, Treaty Rights Office

As members of the Tulalip Tribes, we hear the words “treaty rights” and “sovereignty” all the time. There is no doubt that to each of us they mean something different, yet there are some core principles that stem from these phrases.

Sovereignty is the right to self-determination and self-governance. A sovereign government has the right to govern without outside interference from other groups. Our people were born sovereign as the first nations of this land.

This is of course complex, and so are the tribes’ relationships with other governments. We know that we do not govern without interference from outside forces, especially the federal government. The federal government’s policy regarding tribal rights continues to change and has a significant impact on tribes throughout the country. We’ll discuss more issues around tribal sovereignty in a future article.

The second important thing to define is a treaty. A treaty is a legally binding contract between two or more sovereign nations. It outlines the role each side will play in the future of the relationship and sometimes includes the reasons why they have entered into agreement with one another. Treaty rights are generally considered to be the rights reserved by tribes through treaty and are sometimes called “un-ceded rights” which reflects their existence prior to treaty signing.

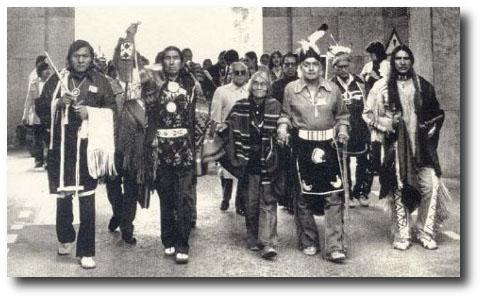

There were five treaties made with northwest Washington tribes; the Treaty of Point Elliott, the Treaty of Point-No-Point, the Treaty of Neah Bay, the Medicine Creek Treaty, and the Treaty with the Quinault. Compared generally to treaties signed with many tribes to the east of Washington they are much more favorable (that is not to say that tribes did not bear an unfair burden of sacrifice). Part of the reason for more favorable treaties is that the United States had a comparatively small standing army, just 15,911 enlisted men, which were tasked with covering a huge geographical area. They did not have the resources to fight wars with a number of tribes in a far off corner of the country. As a result, Governor Isaac Stevens was assigned to make peace and enter into treaties with northwest tribes in order to secure land for settlers in the Washington Territories.

When our ancestors signed the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, the federal government, through its territorial Governor, Isaac I. Stevens, affirmed that the tribes had the inherent right to self-governance and self-determination as outlined in the excerpt from the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Worcester V Georgia,

“The Indian nations had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights, as the undisputed possessors of the soil, from time immemorial,…The very term “nation,” so generally applied to them, means “a people distinct from others.” The constitution, by declaring treaties already made, as well as those to be made, to be the supreme law of the land, has adopted and sanctioned the previous treaties with the Indian nations, and consequently admits their rank among those powers who are capable of making treaties.”

Congress itself defines treaties as the “supreme law of the land” and only signs treaties with other “nations” therefore recognizing tribes as nations and affirming that treaties supersede other laws such as those made by state governments. This excerpt also explains that the U.S. government understood that these rights were “natural rights” implying recognition of tribes’ existence as sovereigns before the creation of The United States.

In the treaty, our ancestors made great sacrifices by ceding millions of acres of land for the promise of medical treatment, education, and permanent access to the resources they had always gathered, including across all of our ancestral lands that lie outside of the reservation.

Article Five of the treaty addresses the most commonly known and arguably most culturally important right,

“The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purposes of curing, together with the privilege of hunting and gathering roots and berries on open and unclaimed land.”

Though truthfully this article was never well defined in law until in 1974 when Judge George Boldt gave his decision in the landmark Indian law case US v Washington (commonly known as the Boldt Decision), where he affirmed what treaty tribes had already known: the phrase “in common with” was meant to be an equal sharing of the salmon runs minus the number of fish needed to spawn future generations.. This court decision, along with a series of subsequent decisions recognized tribes as having equal management authority with the State of Washington over natural resources. This has given tribes a significant role in how fisheries are managed as well as managing tribal hunting. Washington tribes have contributed greatly to the process of salmon recovery and restoration of critical habitats and species. Tulalip has also worked to conserve and enhance the plants and wildlife that our people need to continue to practice our traditional ways.

Tribal and court interpretations of Article Five, secures tribal access to these resources until the end of time and recognizes that any entity whose actions diminish either these resources or our access to them violates the spirit and intent of the treaty.

We know that the treaty is alive and well. It’s as important to us today is it was to our ancestors at the time of signing. We raise our hands to our ancestors and leaders past and present who fought and continue to fight to protect these rights and our way of life.

If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future subjects please send them to ryanmiller@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov

Thank you for reading and we’ll see you next month!