Tulalip Tribes educates community on Treaty Rights

By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

If you’re an avid Instagram user, and let’s face it most of us are, chances are you’ve stumbled across somebody’s profile that is filled with gorgeous photos of mountain ranges, waterfalls, beaches and tall evergreens. Every day, more and more people are exploring the beautiful Pacific Northwest, hiking hidden trails in search of breathtaking views and secret camping grounds.

A 2016 study, conducted by the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office, reported that outdoor recreation generated over twenty billion dollars in this state alone. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, outdoor recreation is a three-hundred-billion-dollar industry and is continuing to grow exponentially. And while it’s important to disconnect, inhale fresh air, enjoy scenery and experience the great outdoors, it’s equally important to remember that this land is sacred and has strong spiritual ties to the original caretakers of this region, who have lived off its resources since time immemorial.

Let’s use the power of imagination to travel back about two-hundred years or so. You’re a young Coast Salish hunter who has been tasked to provide food for your family and village. After many years of cultural teachings, you’re finally ready to head into the woods to get your first elk.

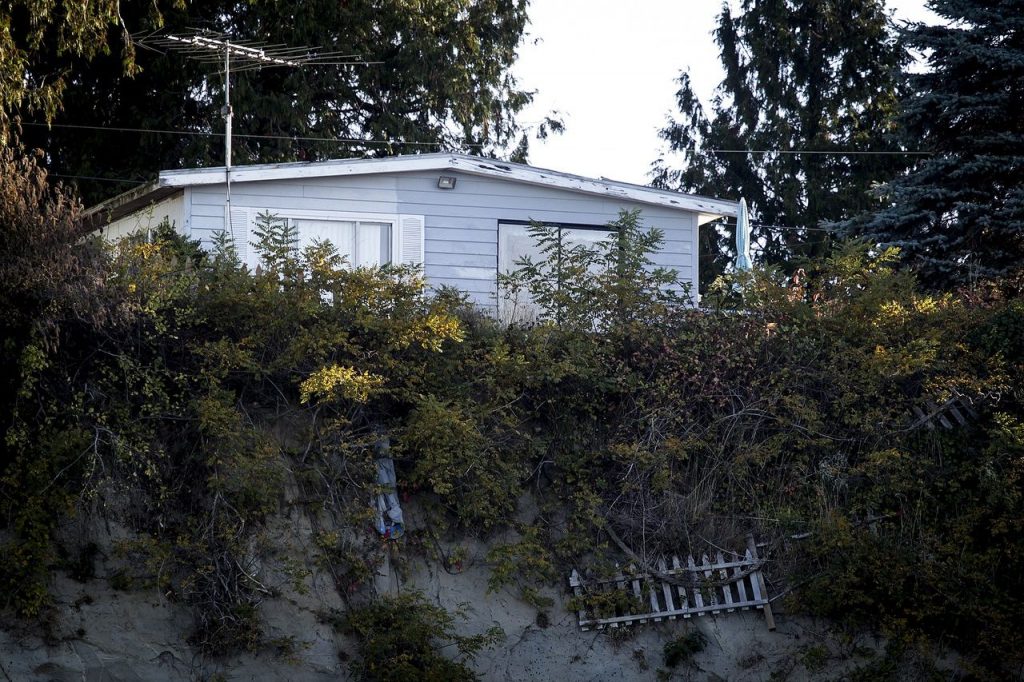

While you’re trekking up to the mountains, you recall all of the stories about elk roaming about in abundance in an area your family has hunted for generations. But you arrive only to see that there are hundreds of people hanging out, sleeping beneath the stars and enjoying themselves in a not-so-quiet manner. Because of all the people and constant foot traffic, there isn’t an elk in sight. So, you decide to try nearby areas to see if the elk have migrated, but instead you’re met with more people. Now you face the dilemma of providing another source of sustenance for your people, who depend on that meat for the upcoming winter months.

Although crowded hunting grounds weren’t an issue two hundred years ago, you can see how big of an impact it would’ve had on tribal villages. When the Coast Salish people signed their treaty one hundred and sixty-four years ago, they kept the right to hunt and harvest on the same lands their ancestors had since the beginning of time.

Fast forward to the summer of 2018. A story was released by a popular local radio broadcast, KUOW, with the headline reading, ‘Seattle Hikers: You may be trampling on tribal treaty rights.’ Within the article, Tulalip Natural Resources Fish and Wildlife Director, Jason Gobin, shared a similar story but in modern time, claiming that many outdoor adventurers are showing a total disregard to the tribe’s ancestral lands. He expressed that due to over congestion, the areas for tribal members to conduct their spiritual work, whether it be hunting, gathering cedar or harvesting huckleberries, has decreased substantially since the signing of the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855.

The story spread like wildfire across Facebook and Twitter as people shared the link, voicing both their support and concern. Over the course of a few months, the article inspired several outdoor recreational organizations and non-profit conservation groups to reach out to the tribe in an effort to learn more about tribal sovereignty. Because of the inquires, the Tulalip Natural Resources department hosted a daylong event for local non-governmental organizations to learn about treaty rights and the history of the Tulalip Tribes.

On the morning of January 9, around thirty individuals from recreational and conservation groups gathered at the Hibulb Cultural Center to begin the day with a tour of the museum. While having fun with the interactive displays, the group gained a basic understanding of tribal lifeways.

“It was a very powerful cultural exhibit, I learned so much I didn’t know before,” expressed Erika Lundahl of the outdoors publishing company, Mountaineers Books. “Particularly about the woolly dogs and also to see the special relationship the people share with the salmon in the area, as well as the weaving and the residential schools. It was powerful to hear first person accounts, it’s a lot to take in. There were things I’ve heard before, but getting a chance to hear the full story is something we all need to look at very closely to get an understanding of the impacts of generational trauma.”

The group then journeyed across the reservation and made their way to the Tulalip Administration building. In conference room 162, Natural Resources’ Environmental Liaison, Ryan Miller, spoke passionately about protecting the treaty rights his ancestors fought to keep.

“Treaty rights are an inherent right,” he explained. “Treaty rights were not given to tribes, it’s a common misconception that the government gives Native Peoples special rights. That’s the exact opposite of how it works. Tribes are sovereign nations, they give up rights and they retain rights. Treaty rights are rights that are not given up by tribes and they’re upheld by the federal government as part of their trust relationship with the treaty tribes. The tribes right to self-govern is the supreme law of the land. It’s woven into the U.S. constitution as well as many legal decisions and legislative articles. The constitution says, congress has the power to make treaties with sovereign nations and that treaties are the supreme law of the land.

“We all love the Pacific Northwest,” he continues. “Other people love it here too and they keep coming back, it’s really getting aggravating. I’m not talking about one person going out and hiking. That’s not the issue. What we’re concerned about, just like the population increasing, is that those people are coming here for what we all love to do, get out into nature. They want to see all those places that you love and I love, that I have a spiritual connection to. We have to figure out a way that we can provide that for people in a way that protects not only the inherent rights of tribes but the resources, so all of us can enjoy it.”

Libby Nelson, Natural Resources Senior Environmental Policy Analyst, gave the group an in depth look at the Point Elliot Treaty. During her presentation, she familiarized the participants with the term, ‘usual and accustomed grounds’. She also touched on the Boldt Decision and spoke of the Tulalip’s current co-stewardship with the U.S. Forestry department, which dedicated an area solely for spiritual use such as berry picking and the annual mountain camp for tribal youth during the summertime.

Natural Resources Special Projects Manager, Patti Gobin, shared a personal and moving story about her grandma, Celum Young, who was a first generation Tulalip boarding school student. As she shared her grandmother’s painful experiences, she quickly followed with a heartwarming story of Celum, depicting her as a woman full of love who struggled loving herself. Because of years of forced assimilation, Celum endured physical abuse for speaking her language and practicing her traditions while at the boarding school. And as a direct result from the boarding schools, Patti admitted that her grandmother never spoke Lushootseed or taught the language to her children and grandchildren, in fear that they would be punished just as she was.

Native children who were around Celum’s age also experienced these atrocities at the boarding schools. Indigenous languages slowly began to slip away from their respective tribal communities. It wasn’t until recently that the language saw a major revitalization within the Tulalip community. Patti shared all this information, weaving together tales of happiness during dark times, to paint a picture that showcases how the trauma from the boarding schools trickled down generation after generation.

Patti then asked the group to help honor tribal treaties, now that they are equipped with more knowledge and understanding of treaty rights and the tribal experience. She suggested signage depicting the tribe’s history as well as murals, such as the ones that will be displayed shortly in Skykomish and the San Juan Islands.

“You don’t have to tell the intimate story of the Stu-hubs people,” she stated. “You can simply begin with the most general knowledge, that there are Indian tribes in the area and we will respect their treaty rights.”

At the end of the presentations, Ryan handed out a list of principals to the recreationalists and conservationists, stating that the tribe wants to be included in any project proposals and to build strong relationships with each organization. He urged them to bring the principals back to their team and discuss and modify the list to meet their mission and values.

“Protection of treaty rights protects endangered species and habitat for all of Washington citizens, not just for tribes,” he said. “All the places that you love, all the species you care about, the orca, the salmon; our treaties are the last line of defense. When our state’s governor was telling the Trump administration that they couldn’t drill for oil off of our coast, he said it would be a violation of tribal treaty rights. We’re the last vanguard, help us protect it. Treaties are the supreme law of the land. They’re living documents and they have as much importance today, to us as Indian People, and they should to you as Washington citizens, as they did the day they were signed.”

The Tulalip Natural Resources Department plans on hosting several more Treaty Rights events like this throughout the year, tailoring their presentations to groups such as environmentalists and governmental entities. For more information, please contact Natural Resources at (360) 716-4480.

Related Articles:

The Treaty of Point Elliott: A living document

Tulalip prepares for Treaty Days

Tulalip youth exercise treaty rights, learn hunting safety

New colonizer in chief, same fight to protect our treaty rights

Tulalip educates community on habitat restoration and treaty rights

Point Elliott Treaty, 159 years later

Tulalip Tribes stewardship recognized by the Harvard Project

Pacific Northwest Tribes unite to protect and defend salmon