By Wade Sheldon, Tulalip News

A red handprint—bold, defiant, and highly symbolic—has become a clear cry for justice in Indigenous communities across North America. What began as a young girl’s silent protest at a track meet quickly grew into a powerful emblem of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) movement. Today, the red handprint represents the pain of lives lost, voices silenced, and families left with unanswered questions. It has become a call to remember, to speak out, and to demand change.

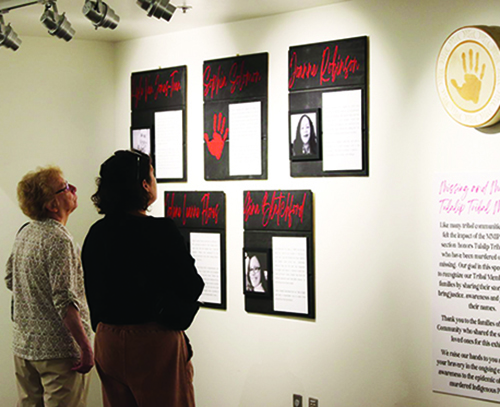

Portraits in Red, the powerful traveling art exhibit by Nayana LaFond, is now on display at the Hibulb Cultural Center in Tulalip. This installation marks its final stop in the Pacific Northwest, after previously touring through Oregon and Idaho. The exhibit opened on Thursday, June 26, and will remain available for viewing through August, though an exact closing date has not been announced. LaFond’s acrylic-on-canvas portraits depict MMIP victims and advocates with raw emotion and reverence. Many subjects are painted with a red handprint across their mouths, a striking symbol of silenced voices and the ongoing fight for justice.

The exhibit invites not just observation but participation. A reflection station set in the middle of the gallery allows visitors to write messages of strength, love, and prayer on ribbons, creating a visual tapestry of solidarity. A nearby earring display invites attendees to hang a single earring on a wire, each one representing a missing or murdered loved one. These additions provide visitors with a way to connect personally with the movement and honor those who are still unaccounted for.

Surrounding the room are portraits of Indigenous individuals who were murdered, disappeared, or rose to prominence as advocates within the MMIP movement. Some are accompanied by short narrative stories of final sightings, painful memories, or lifelong activism. In one corner of the room, a section is dedicated to Tulalip tribal members who have become victims of the MMIP crisis, adding local resonance to the national issue.

Tulalip tribal member Neil Hamilton attended the exhibit with his daughters and reflected on the importance of sharing this history with the next generation. “I think the exhibit was informative, insightful, and brings more awareness for our community to be doing more for ourselves,” he said. “I brought my children so they could see what the red hand movement is all about.”

Artist Nayana LaFond, an enrolled member of the Métis Nation of Ontario, began the series in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 5, recognized as the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, she attended a virtual powwow where people shared selfies marked with red handprints. Rather than post her image, LaFond found herself reading the stories behind the photos, resonating deeply due to her own experience as a domestic violence survivor. “You don’t realize how much you connect to something until you read other people’s stories,” she said.

The first portrait she created was of Lauraina Bear from Saskatchewan. “I thought this would be the only thing I do,” she recalled. But after posting it, the response was overwhelming. She offered to paint more portraits for free, expecting a few requests, and received over 25 in one day. “I realized I couldn’t pick and choose,” LaFond said. “I had to paint them all.” Since then, she has completed more than 100 portraits, most of which were created during the first two years of the pandemic.

Each portrait is made in close collaboration with families or individuals, respecting their cultural beliefs and wishes. “It needed to be about each family,” she emphasized. “Not everybody wants the same thing. Some don’t want a name or likeness shared. So I always try to honor what feels right to them.”

While the project has been artistically transformative, it has also come at a deep emotional cost. “At first it was very cathartic,” LaFond said. “But after a couple of years, it started to feel like retraumatization.” The emotional toll, coupled with unauthorized uses of her artwork, led LaFond to begin winding down the project and returning completed portraits to families. “To do no harm,” she said, “I realized it was time to send them home.”

Despite these challenges, the exhibit has had a measurable impact. One painting helped bring new attention to a missing person case, leading to their recovery. The exhibit has also been used in official reports to the Canadian and Mexican governments, and was made mandatory viewing for Child Protective Services staff in Oregon. “That was huge for me,” she said. “I was grateful for that.”

Still, LaFond sees herself as one voice among many. “There are a lot of artists talking about this now, which is great,” she said. “We’re all speaking the same visual language—black and white portraits, red handprints, symbols of remembrance. It’s that collective voice that’s making real change.”

For more information, visit hibulbculturalcenter.org.