—Swikar Patel/Education Week

By Lesli A. Maxwell Education Week

June 12, 2014

An effort by the Obama administration to overhaul the troubled federal agency that is responsible for the education of tens of thousands of American Indian children is getting major pushback from some tribal leaders and educators, who see the plan as an infringement on their sovereignty and a one-size-fits-all approach that will fail to improve student achievement in Indian Country.

As Barack Obama makes his first visit to Indian Country as president this week, the federal Bureau of Indian Education—which directly operates 57 schools for Native Americans and oversees 126 others run by tribes under contract with the agency—is moving ahead with plans to remake itself into an entity akin to a state department of education that would focus on improving services for tribally operated schools.

A revamped BIE, as envisioned in the proposal, would eventually give up direct operations of schools and push for a menu of education reforms that is strikingly similar to some championed in initiatives such as Race to the Top, including competitive-grant funding to entice tribal schools to adopt teacher-evaluation systems that are linked to student performance.

The proposed reorganization of the BIE comes after years of scathing reports from watchdog groups, including the U.S. Government Accountability Office, and chronic complaints from tribal educators about the agency’s financial and academic mismanagement and failure to advocate more effectively for the needs of schools that serve Native American students. It also comes a year after U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell called the federally funded Indian education system “an embarrassment.” The BIE is overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which is housed within the U.S. Interior Department.

Pushback From Tribes

The proposal, released in April, was drafted by a seven-person “study group” appointed jointly by Ms. Jewell and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. Five of the panel’s members currently serve in the Obama administration.

Some of the nation’s largest tribes, however, are staunchly opposed to the proposal, including the 16 tribes that make up the Great Plains Tribal Chairmans Association, which represents tribal leaders in South Dakota, North Dakota, and Nebraska.

“It’s time for us to decide what our children will learn and how they will learn it because [BIE] has been a failure so far,” Bryan V. Brewer, the chairman of the 40,000-member Oglala Sioux tribe in Pine Ridge, S.D., said last month in a congressional hearing on the BIE.

In the same hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Charles M. Roessel, the director of the BIE and a member of the panel that drafted the plan, said the agency’s reorganization “would allow the BIE to achieve improved results in the form of higher student scores, improved school operations, and increased tribal control over schools.” (Despite multiple requests from Education Week, the BIE did not make Mr. Roessel or any other agency official available for an interview.)

Visit to Standing Rock

President Obama will visit the Standing Rock Sioux reservation on June 13 in Cannon Ball, N.D., and expectations are high that he will announce a major education initiative for tribal schools, which are some of the lowest-performing in the nation. In an op-ed article published last week in Indian Country Today, the president signaled two areas in dire need of federal attention in tribal communities: education and economic development.

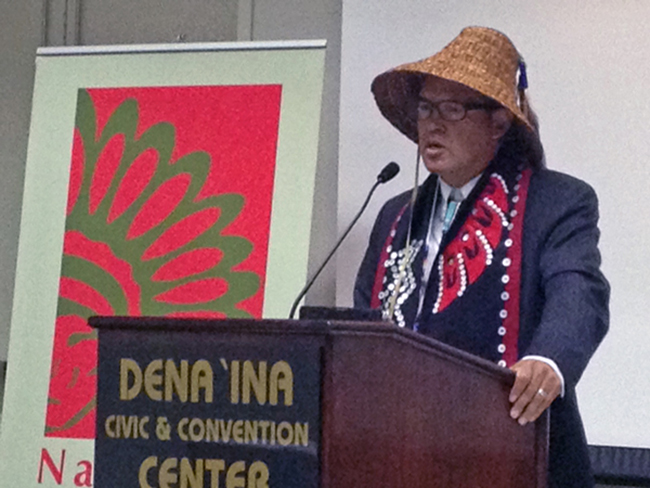

—Swikar Patel/Education Week

Indeed, the achievement picture for American Indian and Alaska Native children is grim. According to federal data, the four-year graduation rate for American Indian and Alaska Native students in 2011-12 was 67 percent, lagging behind all other major student groups except for English-language learners. BIE students, compared to their Native American peers in regular public schools, also scored lower on the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, reading and math tests in 4th grade.

While roughly 90 percent of Native American children attend regular public schools, both on and off reservations, more than 48,000 are enrolled in the BIE system, which includes tribally run schools that are supposed to have autonomy over their operations but rely almost 100 percent on federal funding that flows through the bureau.

Over the years, BIE-operated and -funded schools have faced daunting challenges not unlike those in some of the poorest urban school districts: difficulty recruiting and retaining teachers and school leaders, funding shortfalls, and dilapidated school facilities, to name a few. Mr. Roessel told senators last month that in the current fiscal year, the agency is able to fund just 67 percent of the operational costs needed by the tribally controlled schools it oversees.

Tense History

Tribal educators have complained for years that the agency has not respected tribes’ sovereignty over the schools they run, as spelled out in the Tribally Controlled Schools Act, and has imposed policies that have restricted a major priority for tribes: providing Native language and culture classes.

That history, said one tribal educator, makes the new BIE plan for overhauling itself highly suspect among tribes.

“How we see this plan is simple. The bureau is asking for more money and more staff to continue doing nothing,” said Christopher G. Bordeaux, the executive director of the Oceti Sakowin Education Consortium, a group of tribal schools on the Pine Ridge reservation and other reservations in South Dakota. “For years, we’ve asked the bureau for help, but we never get it. We figure out how to do this stuff on our own. The bureau really has no idea what tribal schools are all about, and they’ve not taken the time to ever listen and learn how to help us, and then they turn around and point to us and say the schools are failing.”

‘Agile Organization’

Under the reorganization plan, the BIE would evolve into an “agile organization” that would focus on supporting school improvement efforts in tribal communities by funding and providing professional development to tribal educators; scaling up recruitment and retention programs to attract talented teachers and school leaders to the often-remote schools; and building and upgrading school facilities, including grossly outdated technology infrastructures in many schools. The plan also calls for developing a single accountability system for BIE schools. Currently, federal law requires BIE schools to adhere to the accountability systems of the 23 states in which they are located, making meaningful comparisons impossible.

Education in Indian Country

On most measures of educational success, Native American students trail every other racial and ethnic subgroup of students. To explore the reasons why, Education Week sent a writer, a photographer, and a videographer to American Indian reservations in South Dakota and California earlier this fall. Their work is featured in a special package of articles, photographs, multimedia, and Commentary.

Full Package: Education in Indian Country: Obstacles and Opportunity

Overview story: Running in Place

Documentary Video: A Long Road Back to the ‘Rez’

The study group’s proposal looks to another set of schools that are also federally run—those operated by the U.S. Department of Defense for the children of active military personnel—as a model for BIE to emulate on how to improve school facilities and student achievement.

The plan also argues that the Tribally Controlled Schools Act “should be made more conducive to reform” so that the BIE can attach conditions to the schools that it funds. For example, the plan calls for requiring the schools that it funds to adopt performance-based evaluation systems that include student achievement results and policies that make it easier to remove underperforming employees. It recommends that BIE launch a pilot of performance-based evaluations this fall in some of the schools it directly operates and expand those into tribally controlled schools in the near future.

To do that, however, the study group said BIE would need funding from Congress that could be used to provide incentives for tribal schools to adopt such reforms. The group recommended that the Interior Department “consider adapting the successful, competitive grants currently being used by the U.S. Department of Education as models” that would help tribes “align tribal educational priorities to President Obama’s education reform agenda to improve student outcomes and ensure all BIE students are college and career ready.”

Looming Court Battle?

Only tribes that operate three or more schools should be eligible for such grants, the study group said.

Any attempts to get around the Tribally Controlled Schools Act would spark major pushback from tribes, said Mr. Bordeaux, who lives on the Pine Ridge reservation and is an elected member of the board of directors for the Washington-based National Indian Education Association.

“Under the law, the BIE does not have this kind of authority over our tribal schools,” he said. “If they continue to do this, the only course we’ll have left is to go to court and file a lawsuit.”

What happens next with the BIE’s proposal is not yet clear. Tribal communities had until June 2 to submit comments on the draft, which will eventually be submitted to Ms. Jewell and Mr. Duncan for their review.

But at last month’s Senate hearing focusing on the BIE’s proposal, Mr. Roessel, the BIE director, assured the panel that the agency wants to improve and is already taking steps to do so.

“We will not build a bigger bureaucracy,” he said. “We will not infringe on sovereignty, and we will not continue to fail.”

While U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, D-Montana, who is the chairman of the Senate committee on Indian Affairs, expressed support for BIE’s improvement efforts, he was also skeptical about the agency’s capacity to follow through. He pointed to Mr. Roessel’s inability to provide answers on how many teacher vacancies are in BIE schools or how many rely on housing provided by tribes.

He said that the Interior Department didn’t provide the committee’s staff with basic information on BIE schools in time for the hearing, despite a request to do so 30 days in advance.

“It almost appears that we’ve got a systemic problem here,” Sen. Tester said. “We don’t have lists on school construction needs, teachers that are not there, very basic stuff.”

Keith Harper says he always wanted a career that helped his people—indigenous people.

Keith Harper says he always wanted a career that helped his people—indigenous people.

NV Energy, part of billionaire Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company, is seeking regulatory approval in Nevada to buy the second US largest solar project to be located on tribal trust lands.

NV Energy, part of billionaire Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company, is seeking regulatory approval in Nevada to buy the second US largest solar project to be located on tribal trust lands.