Author: Kim Kalliber

June 12, 2021 syəcəb

Carolyn Rose Moses

May 4, 1959 – June 7, 2021

Carolyn Rose Moses (Setlakus/Lalacut) was born May 4, 1959 in Powell River, B.C. She was a descendant of Hereditary Chief Johnny Dominick of Klahoose Nation, B.C., and Hereditary Chief Charles Jules of Tulalip. Daughter of William Grenier Jr. (Gladys Grenier) and Elizabeth Harry (Pete Harry). Carolyn spent her childhood years in Sliammon Territory but settled in Tulalip where she married her soul mate Kenneth Moses Jr. on July 16, 1983. Carolyn and Kenneth were married for 28 years and raised two children together, Craig Grenier Moses and Autumnrose Moses.

Carolyn was a residential school survivor and a true warrior for her people. She was a proud Coast Salish woman and spent her life in service to her people. She began in the kitchen cooking for tribal elders, then transferred over to family services where she spent over 20 years helping members of the community. Carolyn advocated for women, children, worked tirelessly helping many people find sobriety, and helped many in their journey along the red road. She wanted people to feel good about themselves and was often heard encouraging someone. She would say “I’m proud of you…you’re doing good.” Carolyn believed in her teachings and had a gift for knowing everyone. She could name every tribal member’s family and many of their relatives going back several generations. She spent 16 years serving on the enrollment committee and used her gifts to help enroll many tribal members and their relatives.

Carolyn had a infectious laugh and a joyful presence that could not be denied and she lit up the room when she walked in. She enjoyed traveling, shopping and lunch with her friends.

Carolyn is survived by her brothers, Murray (Nancy) Mitchell, Leonard (Cathy) Harry, Darryl Wilson, and Laurie (Teresa) Harry; sisters Lillian (Rob) Grenier, Tina (Patrick) Grenier, Toni (Arthur) Grenier, and Sandra (Stan) Harry; and her two children Craig (Florence) Grenier Moses, and Autumnrose (Anthony Enriqurez) Moses. She had eleven grandchildren, Kaeli, Garrett, Gracelyn, Ethan, Liam, Mayah, Cid, Amilio, Benny, James, and Carlos. She was loved by many and was a grandmother, aunt and cousin to numerous individuals in the community.

Funeral Services will be held Saturday, June 12, 2021 at 10:00 AM at the Tulalip Gathering Hall with burial to follow at Mission Beach Cemetery. Arrangements entrusted to Schaefer-Shipman Funeral Home.

yubəč

Honoring King Salmon

By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

Last year, for the first time in over four decades, the Tulalip Tribes made the difficult decision to cancel the Salmon Ceremony to help limit the spread of COVID-19 at the height of the worldwide pandemic. During the yearly event, not only does the Tribe pay respect to the entire salmon species but they also provide the tribal fishermen with a blessing for a plentiful and safe season out on the water, while also sharing good traditional medicine along the way.

After nearly two calendar years, smoke billowed once again from the longhouse overlooking Tulalip Bay on the morning of June 5, as Tulalips gathered in traditional regalia to immerse themselves into their culture, practice the teachings of their ancestors and most importantly recognize, honor and celebrate yubəč, the king salmon.

To really get an understanding of the significance of this ceremony and what it means to the Tulalip people, one must first delve into the Tribe’s history and learn of their stories passed through the generations. As you may know, salmon are integral to the Tulalip culture, diet, and tribal lifeways. Pre-contact, and prior to the current decline of the salmon population, this delicious source of nourishment swam through the Salish Sea, through local rivers and lakes, in abundance. The Tulalips have a traditional story that explains why the salmon returned each year in such great quantities. Back in 1993, Bernie ‘KyKy’ Gobin provided a fantastic retelling of the story Salmon Man, as told by Harriette Shelton-Dover, for the Marysville School District and it goes as follows:

This is one version of the Salmon Man. You might have heard about the Tulalip Salmon Festival. The Salmon Festival was something that was practiced for hundreds of years by the Snohomish people, the sduhubš people. They are also called ‘the salmon people’. And the story’s extremely important because it links to the present day.

And the story goes that there is a tribe of Salmon People that live under the sea. And each year, they send out scouts to visit their homeland. And the way that the Snohomish people recognize that it’s time for the salmon scouts to be returning to their area is when, in the spring, a butterfly comes out. And the first person to see that butterfly will run, as fast as they can, to tell our chiefs or headmen or, now, they are called the chairman. One of the other ways they recognize that the salmon scouts are returning is when the wild spirea tree blooms. The people call it the ironwood tree, and that’s what they use for fish sticks and a lot of other important things, like halibut hooks. It’s a very hard wood. So, when they see either one of these, a tribal member will tell the chairman, and he immediately sends out word to the people and calls them together in the longhouse for a huge feast and celebration to give honor to the visitors that are coming.

The salmon scout will arrive out in the middle of Tulalip Bay there. And the people send out a canoe to meet him. And they put the salmon scout inside the canoe, where a cradle is filled with fern leaves and other soft leaves for a bed for him to come in on and keep him fresh. And he’ll come in by canoe to the cliff right below our longhouse, and, there, the whole tribe will be there on the water to greet him. And they’ll walk him in with songs of honor and just greet him in a special way. Then, he’ll be carried on that cradle up into the longhouse, where he’ll be taken around the fires three times and special songs will be sung in his honor. And they will show him the proper respect he needs as the high chief visitor from the Salmon people. And they will go through some different ceremonies there. Then, they will go up into what is now the tribal center, and prepare the feast. Before the feast, everyone will share in a tiny piece of the salmon and drink a glass of water with it, a little water.

That’s what is done. And then, everyone sits down and feasts and enjoys the salmon and visits with friends and neighbors.

At the end of feast, they get up. Maybe a speech will be made, and, hopefully, it won’t be too long. Then, a song is sung and they bring the remains that are left of the salmon back into the longhouse and thank him for coming and again honor him for the chief that he is and take him back down to the canoe, follow him back down there. And they take him back out and lay his remains back where they picked him up, out in the middle of Tulalip Bay. And, if they have treated that chief properly and showed him the proper respect, and treated him like the king he is, he’ll go back to the Salmon People that live under the sea and he’ll tell them that, “Hey, they greatly honored me. They treated me like I should have been treated. They gave me all the recognition I needed.” And he’ll recommend that the Salmon People return back in abundance.

And the reason to tell this story is because it concerns the environment. And to show that the Snohomish people practiced this for hundreds of years. They gave thanks for many things. One of the things was to honor this great chief from the Salmon People and try to protect his environment and have a place for him to come home to. It’s hard to imagine nowadays this visitor going back and telling them, “Hey, things are all right.” Because he has to tell them, “I’ve been up there, and I entered around Admiralty Head, and I started getting a headache.” And he says, “As I traveled further in I become confused and had a hard time finding Tulalip Bay this time.” And he says, “Worse than that. When I went up the Stillaguamish River my home was gone. Where I was born and raised, it’s not there.”

So, you know, it tells us something, that’s been told a long time: to conserve and keep things and honor all things because they’re alive. The trees are alive. Everything we eat was alive at some time. And we should give thanks and respect these things as living spirits and show them respect appropriately. And if we don’t, we’re going to lose everything as we know it today. The salmon are about gone. The forest is all but gone, and other resources are gone because of greed and mistreatment. We don’t know if we’ll ever be able to restore any of these things. So, this is an important story, the Salmon People story.*

As Bernie mentioned, the Salmon Ceremony was actually practiced for hundreds of years pre-colonialism. During the assimilation era, all Indigenous traditions, ceremonies and even the use of traditional languages were outlawed by the US Government across the country. For several generations, there was no Salmon Ceremony celebration at Tulalip. That is, until 1976 when a group of elders, led by Harriette Shelton-Dover, brought the tradition back.

Said Tulalip Vice-Chairman Glen Gobin, “after the treaty signing and after the boarding school era, much of our teachings were taken away. We were not able to speak our languages. We were not able to live with our families. Much of what we had as a culture was disappearing quickly. Some of the elders remembered certain aspects and would share those memories of how things used to be. The elders in 1976, Harriette in particular, said we need to revive Salmon Ceremony, we need to bring it back. She gathered up different elders and they pieced together what each of them knew about the Salmon Ceremony from either things they personally witnessed or things they heard their grandparents talk about.”

He continued, “Harriette always said that so much was taken from us and what we do today may not be exactly the same way it was done two hundred years ago. But as long as we do it with good intentions and with a pure heart, our elders will receive it in that manner. So, we hang on to those bits and pieces that we have and we’re thankful for them.”

Ever since the revival, with the exception of 2020, the Tribe has turned out in large numbers, adorning cedar woven hats and headbands, traditional shawls, and beaded jewelry to welcome the guest of honor, the representative hailing from the underwater village. They sing passionately in the language of the ancestors, they keep time with elk and deer hide hand drums. They dance and feast in honor of the salmon people. And they keep the traditions and teachings of their own people alive and strong.

* Bates, Ann and Karen Bayne. 1993. Tulalip History and Culture: Supplemental Class Materials. Marysville: The Tulalip Tribes, Marysville School District, Catholic Community Services of Snohomish County. https://www.tulaliplearningjourney.org

‘Seeds of Culture’ shares stories of endurance, culture and hope for the future

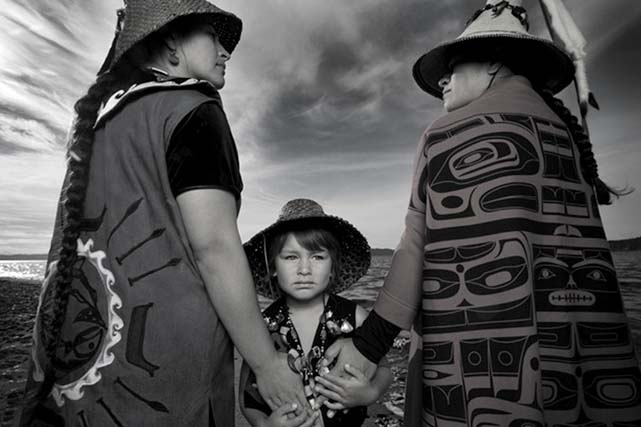

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News; photos by Matika Wilbur

It’s been nearly a decade since Tulalip tribal member and celebrated visual storyteller Matika Wilbur made the bold decision to sell nearly everything she owned to begin an unprecedented journey of collecting the boundless beauty of Native American culture. Her journey is known as Project 562, a multi-year national photography project dedicated to photographing over 562 federally recognized tribes in the United States.

To unveil the true essence of contemporary Native issues and the magnitude of tradition, Matika travelled hundreds of thousands of miles, many in her RV dubbed ‘the Big Girl’, but also by horseback, train, plane, boat and on foot across all 48 continental states, Hawaii, deep into the Canadian tundra and into Alaska. The depths of her travels reflect her steadfast commitment to visit, engage, and photograph at least 562 federally recognized tribes, while also revealing her passion to inspire and educate.

“While teaching at Tulalip Heritage High School and attempting to create a photography curriculum with a narrative that our children deserve, I found an outdated narrative. It’s an incomplete story that perpetuates an American historical amnesia. It’s a story that’s romantic and dire…it’s the story of extinction,” she recalled of the circumstances that led to her life changing journey.

Matika points out the extinction theme often associated with Native America is easily perceived by doing a quick Google Images search. If you search for ‘African American’, ‘Hispanic American’ or ‘Asian American’, then you’ll find images of present day citizens who represent each culture. You’ll see proud, smiling faces and depictions of happy families. But if you search for ‘Native American’ the results are very different. You’ll see mostly black and white photos of centuries old, stoic Natives who are “leathered and feathered”.

“All of these images and misconceptions contribute to the collective consciousness of the American people, but more importantly it affects us in the ways that we imagine ourselves, in the ways we dream of possibility,” she explained.

And so began her multi-year mission to photograph and collect stories of contemporary Indigenous citizens from the hundreds of sovereign nations that make up Native America. As her photography portfolio continued to expand, so too did her realm of possibility.

Today, the now 37-year-old Matika has come to realize that Indigenous identity far surpasses federal acknowledgement. There are state-recognized tribes, urban and rural Native communities, and other spaces for Indigenous identity that don’t fall under the U.S. government’s recognition. Astonishingly, she estimates she has photographed close to 1,000 different tribal communities.

In a respectful way, Matika has been welcomed into one tribal community after another because they not only support her project whole-heartedly, but also because they desire to see things change. From media coverage to Google Images search results to what’s written in history books, Native Americans deserve an accurate portrayal of their vibrant, color-filled imagery and oral histories that have been passed down for generations.

Conversations about tribal sovereignty, self-determination, holistic wellness, historical trauma, decolonization of the mind, and revitalization of culture accompany the vast collection of photographs, videos, and audio recordings Matika has diligently collected. This creative, consciousness-shifting work will be widely distributed through national curricula, artistic publications, exhibitions, and online portals.

Melding powerful storytelling with video, photography and song, Matika expanded on her experiences photographing Native American women across the hundreds of sovereign nations she has visited for nearly a decade during her special guest appearance at the Mount Baker Theatre in Bellingham. Her captivating June 3rd presentation was at a social distanced max capacity. Upon concluding the audience showed their respect for the evening’s eye-opening and heartwarming cultural exchange with a loud standing ovation.

“So far I’ve had the opportunity to share my journey with audiences at museums, universities, conferences, and galleries across the United States,” stated Matika. “I strive to share stories and photographs of contemporary Indigenous people as the positive role models I know them to be.

“The most amazing part of the journey has been the generosity, kindness, and knowledge that Native people have offered me. I have met activists, educators, culture-bearers, artists, and students. The topics of their stories vary – from tribal sovereignty and self-determination, to recovery from historical trauma and revitalization of culture. They have transformed and inspired me, and I want to do my part to share their stories.”

Here are just a few of those riveting stories accompanied by stunning photos that were shared during Matika’s Mount Baker Theatre presentation – Seeds of Culture: The Portraits and Voices of Native American Women.

Darkfeather Ancheta is pictured with her sister and nephew at the edge of Tulalip Bay. They are wearing the traditional regalia that was prepared for their annual Canoe Journey. Every year, upward of 100 U.S. tribes, Canadian First Nations and New Zealand canoe families will make “the journey” by pulling their canoes to a rotating host destination tribe. Canoe families pull for weeks, and upon landing, there will be several days and nights of “protocol”: a celebration of shared traditional knowledge, ancestral songs, and sacred dances.

This celebration has been incredibly important to Darkfeather. She says, “It didn’t change me. It raised me. It shaped me. It’s just who we are, and where we come from…it revitalizes our cultural ways. There are so many teachings that go along with the relationship with the canoe. We take care of the canoe and it takes care of us. When we’re on the water, we all have to pull together. Everything is smoother when we all work together. The teachings that the elders gave to us – like, respecting ourselves, respecting each other, respecting other people’s songs, their dances, and their teachings – they teach us how to walk in the world. And the music and songs are so powerful. It’s all so beautiful. It touches you down into your soul. It helps you get through hard times, both in the water and in life”.

Dr. Mary Evelyn Belgarde is a retired professor of Indian education from the University of New Mexico. She has collaborated in establishing several charter schools focused on Indigenous education. She has raised funds to support thousands of Native students. She is very passionate about training culturally competent teachers to work within Indigenous communities. She is well-versed in the history of boarding schools and governmentally-engineered education systems of assimilation.

During our conversation she asked, “When are we going to stop asking our children to choose between cultural education and western education? I think we are ready to stop the assimilation process. The time to change is now.”

Former vice-chairwoman for the Tulalip Tribes, Deborah Parker is a prominent advocate for tribal women’s rights and well-being, as is her daughter, Kayah George. She advocated on behalf of Native women during the fight to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which was held up in Congress due to specific provisions that would protect Native women and tribal sovereignty.

Deborah said, “As a survivor of domestic violence, I knew that I would someday be able to help another person,” she said. “When you are asked to protect someone, when you are asked to protect a nation, that is what you do. You armor up. … For me, it will be a lifetime of this work. It will never stop because every woman is worth protecting. Every man and every woman deserves justice.”

Calling Walwatoa (Jemez Pueblo), New Mexico home, Juanita is a community wellness advocate and works for her tribe’s community wellness program. She lives on her tribal lands, and feels grateful for the opportunity to serve her people. Born in Washington, DC while her mother was working for the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Juanita moved back to her community when she was young.

Her mother “wanted my brother and I to know the language and the culture, and that’s a big part of why I continue to reside on the reservation, because growing up it’s become a big part of who I am and my identity as a human being. Even though I’m mixed, I’m half Indigenous and half African American, I tend to identify more with the Indigenous side, only because I grew up on the reservation. Culture and family is why I’m here, and my mom is a big reason also, and that attachment to family and land is why I’m still here on the rez. I’m a rez kid at heart.”

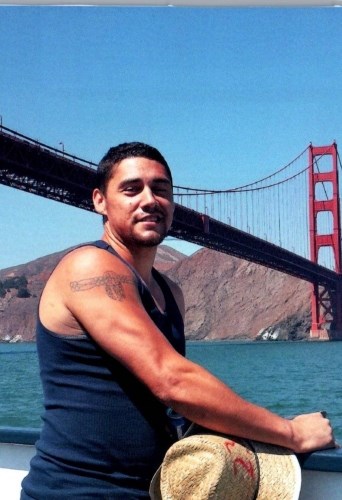

Warren Michael Moses

September 11, 1981 – June 5, 2021

It is with deep sadness and heavy hearts that we announce the passing of Warren Michael Moses, beloved son, grandson, father, brother, nephew and cousin. Warren went to be with our dear Lord on June 5, 2021 with his loving grandmother and mother by his side.

He was born on September 11, 1981 to Robert (Bebop) Moses Jr. and Kim Bustamante. Warren and his brothers were raised by his wonderful grandmother Johanna Moses and auntie in Tulalip after their father passed away. Warren was a Tulalip Tribal Member. He graduated from Marysville Pilchuck High School in 2000, and continued his education at Haskell University. He was very loving and sweet, a gentleman with a beautiful personality. He enjoyed playing and watching sports, especially his Seahawks. Warren was extremely gifted in music. He was the life of the party. He will be deeply missed by his family and friends. A star gone to soon.

He is preceded in death by his father, Robert (Bebop) Moses Jr.; grandfather, Robert Moses Sr.; Great Grandparents, Marya Jones Moses and Walter Moses Sr., Albert and Annie Moses. He leaves behind his son, Ira Moses-Snyder; grandmother, Johanna Moses; mother, Kim Bustamante; siblings, Athena Moses (Rob), Aimee Moses, Lorne Moses and Blake Moses; His nieces and nephews, Tianna Moses, Kiera Moses, D?sean Moses, Kathryn Elliott, Kohen, Kaine, KamBrea, Kendalyn and Kwynn Moses; Great niece Aaliyah-Camari Downing, former wife dear to his heart, Kimberly Moses along with her children, Austin Bercier, Marissa Bercier, Kaitlin Murray and Victoria Murray; and her grandchildren, Hunter Wilson and Lilliana Baker; Uncles, Jon Moses Sr, Anthony Moses Sr, Aaron Moses Sr, William Moses and most adored auntie Anna Moses; Uncles, Marvin, Benjamin, Allen Burchell; Aunt, Rachel Proper; as well as several cousins, friends, and family.

Funeral Service Friday, June 11, 2021 at 10:00 AM at the Tulalip Gathering Hall with burial to follow at Mission Beach Cemetery. Arrangements entrusted to Schaefer-Shipman Funeral Home.

Fallen TPD hero honored at Washington State Peace Officers Memorial Ceremony

By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

Five flags were carried onto the stage of a dimly lit gymnasium, at St. Martin’s University in Lacey, on the afternoon of June 4. Seated opposite of the stage were the families of fourteen Washington State police officers whose lives were lost over the past two years. Every year, the Behind the Badge Foundation organizes the Washington State Peace Officers Memorial Ceremony to honor those brave officers who paid the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty. This year, five officers who passed away due to COVID-19 related complications were also included in the special honoring.

Fourteen banners lined the entryway of the gym, each depicting the picture of a fallen officer and also featured a short bio that described the life and times of the hero behind the badge. Moving musical performances were dedicated to the officers, including the National Anthem by Detective Adele O’Rourke of the Renton Police Department, an original number titled ‘Carved in Stone’ by Shaun Bebe of the Ocean Shores Police Department, and a bagpipe rendition of Amazing Grace.

“Behind the Badge is a foundation that supports law enforcement officers and their families in times of critical need,” said Behind the Badge Executive Director, Brian Johnston. “As we began building this foundation, our eyes were opened to so many needs within the law enforcement community and within our family community. Healthy officers and healthy family equal healthy communities. From the response side of trying to support our law enforcement officers and their families in a line of duty death, or even a suicide death or unexpected death, we think it’s very important to continue to build the relationship with the department and the families so they feel supported throughout time. The other part of that is that there is significant honor in being a police officer and if you were to lose your life in any form of law enforcement, there are things we should be doing to memorialize that person’s service, duty and life.”

The touching tribute featured prayers and heartfelt messages from state officials and a handful of leaders of police departments across the state.

During the reading of the roll call of honor, a single rose was placed into a vase each time a fallen hero’s name was said aloud. A family sitting near the back of the audience watched intently, wiping tears from their eyes, waiting for their loved one’s name to be called, and they held each other close when they heard, “Officer Charlie Joe Cortez, of the Tulalip Police Department,” over the loudspeaker.

“This to me is about making sure that they will never be forgotten, that they’re honored for the sacrifices that they made to their communities that they loved,” expressed Charlie’s mother, Paula Cortez. “It was special for me to know there are still people out there who care and are willing to let us know that our fallen officers will not be forgotten and that their sacrifice was worth something. The Behind the Badge Foundation said ‘it was their duty to serve and it’s our duty to remember’ so that’s what this ceremony is about.”

The two-hour memorial ceremony ended with a trumpet performance of TAPS and a 21-gun salute in honor of those fourteen officers who died protecting and serving their communities. The families were then invited to make a ten-minute journey across town to the State Capitol to view the Washington State Law Enforcement Memorial Wall, overlooking Capitol Lake, where the names of the fourteen officers were recently inscribed.

Before heading over to the memorial wall, Charlie’s family and his fellow TPD officers took a second to snap a few photos with Charlie’s banner, a special moment for his children who wore smiles when posing next to the life-sized photo of Charlie.

Said TPD Chief of Police Chris Sutter, “It’s a real special day to honor and pay our respects to the officers in our state who have given the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty and we’re here representing the Tulalip tribal police department in honor of Officer Charlie Joe Cortez. Our thoughts and prayers, every day, go out to officer Cortez and family, all of his loved ones and friends and co-workers and tribal community who love and support him so much.”

Upon arrival at the memorial wall, which was also funded and designed by the Behind the Badge Foundation, blank sheets of paper and pencils were distributed to the family members so they could trace their fallen hero’s name onto the paper and take home a special memento to commemorate the day of honoring.

“It’s a permanent reminder for generations to come,” Chief Sutter said. “To see these names on that wall, it’s a very sacred place and a reminder of the sacrifice that women and men in our state have given in the line of duty for public safety. It’s a very highly reverent place for law enforcement.”

Charlie’s lifelong friend and fellow TPD Officer, Beau Jess, attended the memorial ceremony that day and plans on visiting the memorial wall with his family in the near future. Working through some tough emotions after a beautiful ceremony Beau shared, “this one is hard in particular because I’ve known him my whole life. It’s more than just a badge for me, it’s legitimately losing a brother. It’s good for closure, especially after not having any.”

A video recording of the 2021 Washington State Peace Officers Memorial Ceremony will be posted online at www.behindthebadgefoundation.org in the upcoming days.

It has been seven months since Officer Cortez was announced lost at sea, and the search for his body continues. Charlie’s family is determined by all means to bring the fallen Tulalip hero home. A memorial service for Charlie is planned for 1:00 p.m. August 17, at the Angel of the Winds Arena with a meal to follow at the Tulalip Gathering Hall.

Thank you for keeping Charlie’s family and the Tulalip Police Department in your prayers. As always, please send any potential evidence, information or your own informal searches to us by texting 360-926-5059, or emailing bringofficercortezhome@gmail.com, or leaving a voicemail at (909) 294-6356.

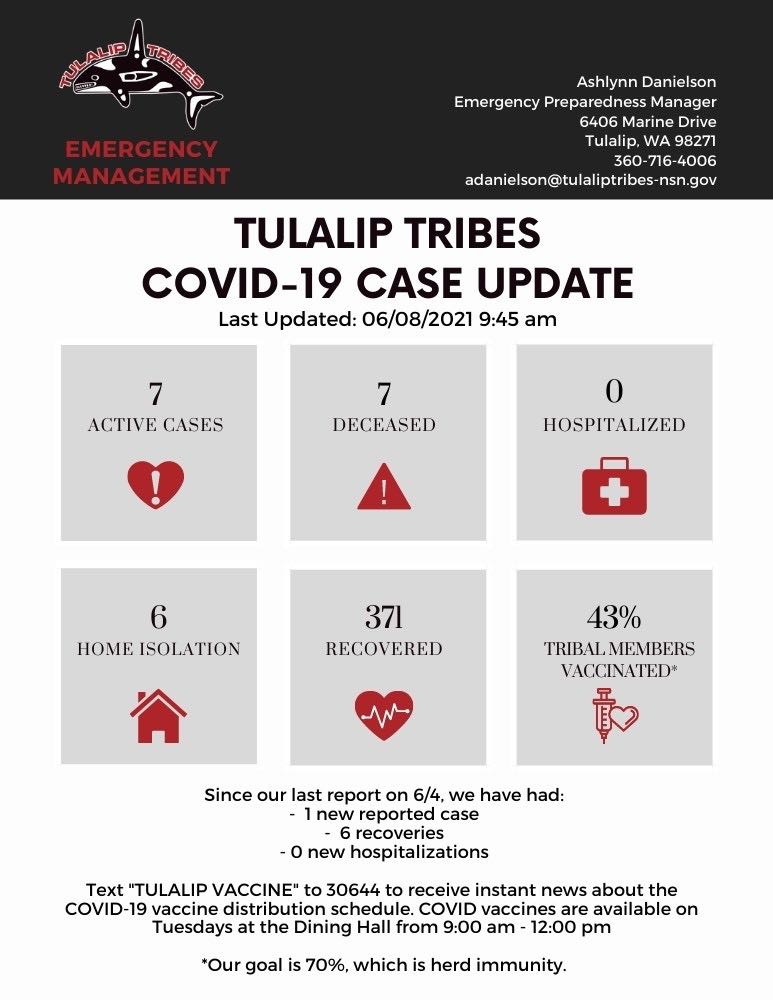

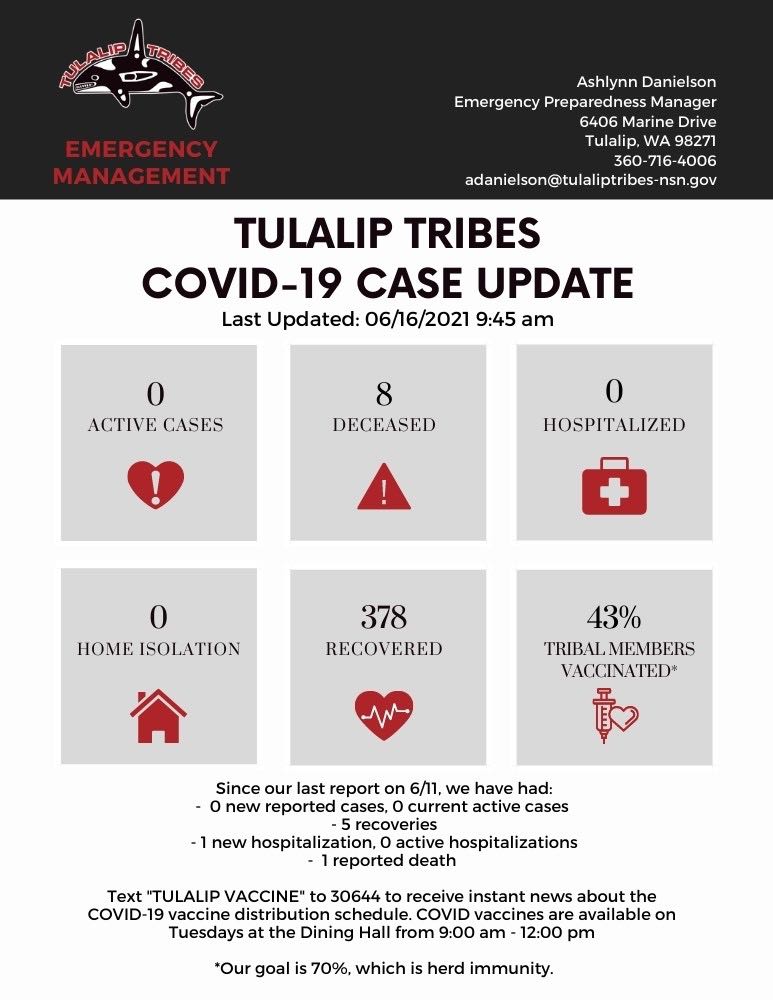

Covid Case Update, June 8, 2021

June 5, 2021 syəcəb

stəgʷad (Salmonberry) season

Submitted by AnneCherise Jensen

stəgʷad (Salmonberries) play an important role in the culture, traditions and way of life of many Native Americans tribes – all the way from the west coast of Northern California, through Canada, and up to Alaska. Traditionally, the Salmonberry is named after Coast Salish Native Americans fondness for eating the berries with both salmon & salmon roe. Salmonberries also play a significance in similarity in how they look a lot like salmon roe, with their orangey-pink color of the berries. The berries were generally eaten fresh, due to their high water content and difficulty to preserve – and considered a delicacy in Native American culture. To this day, salmonberries have also been known to be made into jams and jellies, and can be preserved by freezing.

Salmonberries are the earliest berry to ripen and harvest in the Spring, harvested anywhere as early May to late July depending on the elevation of the berry shrubs. Lower elevation bushes will be the first to ripen, while higher elevation will ripen later in summer. Salmonberry bushes tend to have fewer thorns than some other berry species, and typically make for a smooth and pleasant harvest. Salmonberry colors vary from dark red, to pink, to bright orange. Each color tends to have its own unique flavor, with the vibrant red known to be slightly sweeter and the orange berries slightly more tart. They are a native northwest plant, growing in abundance in marshy, wetland and forested areas with nutrient rich, unbothered soils.

Salmonberries are an extremely nutrient dense and healthy food, some may also even refer to it as a superfood. Salmonberries are packed with vitamins, minerals and antioxidants that help nourish & replenish the body. They are especially high in vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin E, Manganese, fiber and rich phytonutrients. Here is the nutrient information on one serving (1 cup) of salmonberries. As you can see, salmonberries are an excellent source of vitamins and minerals and are a great traditional food to add to your diet this time of year.

Serving Size: 8 oz or 1 cup

Nutrient % Daily Value (% Daily Value is the percentage of the Daily Value for each nutrient in a serving of the food. The Daily Values are recommendation amounts of nutrients for individuals to consume each day for optimal health outcomes )

- Fiber 15%

- Folate 10%

- Riboflavin 11%

- Phosphorus 9%

- Magnesium 9%

- Manganese 108%

- Vitamin A 22%

- Vitamin B6 14%

- Vitamin C 23%

- Vitamin E 16%

- Vitamin K 34%

stəgʷad Salmonberry Jam recipe

Salmonberry jam is a great way to preserve and utilize a large salmonberry harvest. The jam can either be made within 24 hours after harvest, or you can freeze them and make the jam at a later time. The sugar to berry ratio is as follows; Measure the berries to find out how many cups you have and put them in a saucepan. Measure out 2/3 cup of sugar for every 1 cup of berries. For example, for three cups of berries, you will need 2 cups of sugar. For every 3 cups of berries, you will need a half a cup of lemon juice.

Ingredients:

- 3 cups Salmon Berries

- 2 cups sugar

- 1/2 cup lemon juice

Directions:

- Rinse salmon berries in light lukewarm water.

- Add salmonberries, sugar and lemon juice into a large saucepan. Your ingredient measurements may vary depending on how many berries you plan to process.

- Turn the saucepan on medium heat and mix all ingredients together. Allow to warm up the mixture for about 15 minutes.

- Once ingredients start to warm up, use a potato masher to slowly break down the berries into smaller pieces.

- Once berries are broken down – turn the heat up and allow the jam mixture to boil anywhere from 5-8 minutes. This will create a thicker consistency and the volume of the mixture should reduce to half.

- After boiling, turn on low and allow to simmer for an additional 10-15 minutes.

- Test the thickness of the jam by taking out a teaspoon and allowing it to cool.

- Once you get a thickness you like – remove from stove top and place into your favorite container.

- Refrigerate. Should last approx a year in the refrigerator.

- Enjoy salmonberry jam on some whole wheat toast, protein pancakes, or some vanilla frozen yogurt!

**This material was funded by USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – SNAP. This institution is an equal opportunity provider.

Sources:

https://www.nutritionvalue.org/Salmonberries

http://nativeplantspnw.com/salmonberry-rubus-spectabilis/