By NATE SCHWEBER

FORT BELKNAP AGENCY, Mont. — In the employee directory of the Fort Belknap Reservation, Bronc Speak Thunder’s title is buffalo wrangler.

In 2012, Mr. Speak Thunder drove a livestock trailer in a convoy from Yellowstone National Park that returned genetically pure bison to tribal land in northeastern Montana for the first time in 140 years. Mr. Speak Thunder, 32, is one of a growing number of younger Native Americans who are helping to restore native animals to tribal lands across the Northern Great Plains, in the Dakotas, Montana and parts of Nebraska.

They include people like Robert Goodman, an Oglala Lakota Sioux, who moved away from his reservation in the early 2000s and earned a degree in wildlife management. When he graduated in 2005, he could not find work in that field, so he took a job in construction in Rapid City, S.D.

Then he learned of work that would bring him home. The parks and recreation department of the Pine Ridge Reservation, where he grew up, needed someone to help restore rare native wildlife — including the swift fox, a small, tan wild dog revered for its cleverness. In 2009, Mr. Goodman held a six-pound transplant by its scruff and showed it by firelight to a circle of tribal elders, members of a reconvened warrior society that had disbanded when the foxes disappeared.

“I have never been that traditional,” said Mr. Goodman, 33, who released that fox and others into the wild after the ceremony. “But that was spiritual to me.”

For a native wildlife reintroduction to work, native habitat is needed, biologists say. On the Northern Great Plains, that habitat is the original grass, never sliced by a farmer’s plow.

Unplowed temperate grassland is the least protected large ecosystem on earth, according to the American Prairie Reserve, a nonprofit organization dedicated to grassland preservation. Tribes on America’s Northern Plains, however, have left their grasslands largely intact.

More than 70 percent of tribal land in the Northern Plains is unplowed, compared with around 60 percent of private land, the World Wildlife Fund said. Around 90 million acres of unplowed grasses remain on the Northern Plains. Tribes on 14 reservations here saved about 10 percent of that 90 million — an area bigger than New Jersey and Massachusetts combined.

“Tribes are to be applauded for saving so much habitat,” said Dean E. Biggins, a wildlife biologist for the United States Geological Survey.

Wildlife stewardship on the Northern Plains’ prairies, bluffs and badlands is spread fairly evenly among private, public and tribal lands, conservationists say. But for a few of the rarest native animals, tribal land has been more welcoming.

The swift fox, for example, was once considered for listing as an endangered species after it was killed in droves by agricultural poison and coyotes that proliferated after the elimination of wolves. Now it has been reintroduced in six habitats, four on tribal lands.

“I felt a sense of pride trying to get these little guys to survive,” said Les Bighorn, 54, a tribe member and game warden at Montana’s Fort Peck Reservation who in 2005 led a reintroduction of swift foxes.

Mr. Speak Thunder, who took part in the bison convoy, agreed. “A lot of younger folks are searching, seeking out interesting experiences,” he said. “I have a lot of friends who just want to ride with me some days and help out.”

Over the last four years in Montana, the tribes at Fort Peck and Fort Belknap, along with the tycoon and philanthropist Ted Turner, saved dozens of bison that had migrated from Yellowstone. Once the food staple of Native Americans on the Great Plains, bison were virtually exterminated in the late 19th century; the Yellowstone bison are genetic descendants of the only ones that escaped in the wild.

This spring, by contrast, Yellowstone officials captured about 300 bison and sent them to slaughterhouses. Al Nash, a park spokesman, said they were culled after state and federal agencies “worked together to address bison management issues.” The cattle industry opposes wild bison for fear the animals might compete with domestic cows for grass, damage fences or spread disease.

Emily Boyd-Valandra, 29, a wildlife biologist at the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, is emblematic of new tribal wildlife managers working around the Northern Plains. She went to college and studied ecology. (Nationwide, the rate of indigenous people in America attending college has doubled since 1970, according to the American Indian College Fund.)

Diploma in hand, Ms. Boyd-Valandra moved home, took a job with her tribe’s department of game, fish and parks, and found a place for what she called “education to bridge the gap between traditional culture and science.”

Blending her college lessons with the reverence for native animals she absorbed from her elders, she helped safeguard black-footed ferrets on her reservation from threats like disease and habitat fragmentation. The animal was twice declared extinct after its primary prey, the prairie dog, was wiped out across 97 percent of its historic range; since 2000, ferrets have been reintroduced in 13 American habitats, five of them on tribal land.

“Now that we’re getting our own people back here,” Ms. Boyd-Valandra said, “you get the work and also the passion and the connection.” One of her mentors is Shaun Grassel, 42, a biologist for the Lower Brule Indian Reservation in South Dakota. “What’s happening gives me a lot of hope,” he said.

Though each reservation is sovereign, wildlife restoration has been guided to a degree by grants from the federal government. Since 2002, the Fish and Wildlife Service has given $60 million to 170 tribes for 300 projects that aided unique Western species, including gray wolves, bighorn sheep, Lahontan cutthroat trout and bison.

“Tribal land in the U.S. is about equal to all our national wildlife refuges,” said D. J. Monette of the wildlife agency. “So tribes really have an equal opportunity to protect critters.”

Nonprofit conservation organizations have also helped. But tribe leaders say that what drives their efforts is a cultural memory that was passed down from ancestors who knew the land before European settlement — when it teemed with wildlife.

“Part of our connection with the land is to put animals back,” said Mark Azure, 54, the president of the Fort Belknap tribe. “And as Indian people, we can use Indian country.”

In late 2013, during the painful federal sequestration that forced layoffs on reservations, Mr. Azure authorized the reintroduction of 32 bison from Yellowstone and 32 black-footed ferrets. That helped secure several thousand dollars from the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife and kept some tribe members at work on the reintroduction projects, providing employment through an economic dip and advancing the tribe’s long-term vision of native ecosystem restoration. The next project is an aviary for eagles.

One night last fall, Kristy Bly, 42, a biologist from the World Wildlife Fund, visited the reservation to check on the transplanted black-footed ferrets. Mena Limpy-Goings, 39, a tribe member, asked to ride along because she had never seen one.

They drove around a bison pasture under the Northern Lights for hours, until the spotlight mounted on Ms. Bly’s pickup reflected off the eyes of a ferret dancing atop a prairie dog burrow.

“Yee-hoo!” Ms. Bly cheered. “You’re looking at one of only 500 alive in the wild.”

Ms. Limpy-Goings hugged herself.

“It is,” she said, “more beautiful than I ever imagined.”

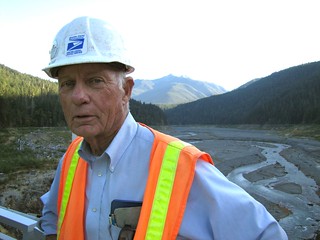

![UPDATED — Only debris left to clean up as Elwha River is free to travel its own path [ **WITH VIDEO ** ]](https://www.tulalipnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Elwha_River_-_Humes_Ranch_Area2-50x50.jpg)