We recommend using the gallery view to read the comic book pages excerpted from the next issue of Tribal Force.

Comic books may be meant for kids, but they’re not child’s play. So says Jon Proudstar, creator of Tribal Force – the first comic book to feature an all-Native American superhero team.

Time spent counseling child-abuse victims and violent youth offenders – often from the Pascua Yaqui and Tohono O’odham reservations near his Tucson, Ariz., home – taught Proudstar the value of cultural awareness. He didn’t learn about his own Yaqui heritage until his maternal grandmother told him when he was 5.

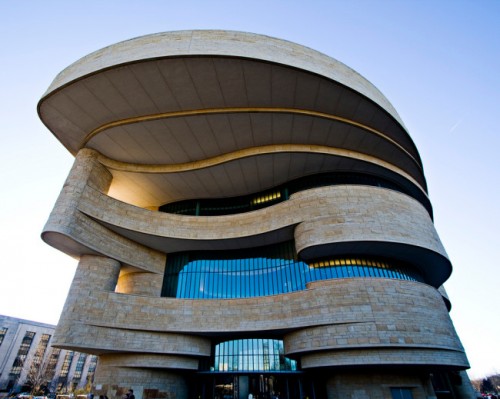

Tribal Force, released in 1996, was critically well received – even making it into “Comic Art Indigène,” a pop-culture exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Several large comic-book publishers sought to buy the rights, but Proudstar wanted to retain control of the storyline and the characters’ unhappy, all-too-real backstories. Unfortunately, he lacked funding, so the project went dark for more than a decade.

The new Tribal Force, from the small independent publisher Rising Sun Comics, continues the saga. An online preview is already available, with the print version expected in April.

The god Thunder Eagle, determined to create a Native superhero team from North America’s various First Nations, helps Nita, a Navajo child-molestation survivor, transform into the goddess Earth. Meanwhile, Gabriel Medicine Dog, a Hunkpapa Sioux left mute by fetal alcohol syndrome, metamorphoses into the fearsome Little Big Horn following a fatal bar fight. Together, Nita and Gabriel seek out other Native supernaturals, fighting high-tech government entities and supervillains along the way.

A onetime Hollywood chauffeur and bodyguard, Proudstar, 46, currently works as a screenwriter and independent-film actor. In 2012, he co-starred with Booboo Stewart of the Twilight franchise in the award-winning coming-of-age film Running Deer. He formed Proudstar Productions to represent and finance deserving projects, including the forthcoming Wastelander, an apocalyptic science fiction film directed by Arizona’s Angelo Lopes. HCN contributor Bryn Bailer caught up with Proudstar recently in a Tucson coffee shop.

High Country News Why did you create Tribal Force?

Jon Proudstar I think Native children need to know who they are. They forget why we fought so hard in the beginning, and why we continue to fight: to fulfill the promise we made with our God to protect this land and take care of it. When you have that strength of knowing where you come from, the greatness your people once had, it’s like you’re Superman. You feel the power.

HCN Where did the idea come from?

Proudstar The superhero comic books that I was so into (as a kid) taught me the whole thing about good and evil. I saw the bad things that were going on, that gangs were doing, and … I know it sounds silly, man, but I was like: “Spider-Man wouldn’t do that,” or “Batman wouldn’t do that.”

HCN Traditionalism vs. modern life is a big theme, isn’t it?

Proudstar That’s definitely entrenched in Tribal Force. They’re all traditional heroes – meaning that their powers come from Native tradition – but their enemies are all high-tech: guns, lasers, cannons, invisible ships. That’s what they’re up against.

It’s hard to keep values and traditions when you’re amalgamating with such an advanced society. You walk two roads: Failure in one world is success in the other, and vice versa. … My dream is to give Native American kids heroes. I didn’t have that.

HCN The members of Tribal Force aren’t your typical superhero team.

Proudstar The characters are very young and flawed, and not into their culture. They’re the last people you’d pick to have super powers in your community. They’re the jerkoffs who are in jail every frickin’ weekend.

Nita’s a punk … and the gods won’t take it from her any more. Spiderwoman – the Navajo goddess who taught her people how to weave – takes Nita to the past, and shows her what the Navajo have been through. When she sees the sacrifices that her people made, she starts to become more

serious about learning. If she learns how to weave, she’ll get more powers. If she goes through her Kinaaldá (a Navajo coming-of-age ceremony) she’ll increase her powers.

HCN If the members of Tribal Force were here today, what would they be most upset with?

Proudstar Tribal Force looks at the same issues that rez kids have to deal with. When I was younger, I remember thinking, “We’ll always be poor, struggling, seeing relatives being arrested.” That was kind of crushing. But I educated myself by reading a lot, and in broadening my horizons, I realized that things will change – and that you can change them.

The first issue I’m dealing with in the book is the epidemic of child molestation on Indian reservations. Seven out of 10 girls – it’s a huge cancer. Gabe has fetal alcohol syndrome … and he’s into weed and drinking, and struggles with learning what it truly is to be a warrior. A lot of kids misinterpret what a warrior is. It has nothing to do with war. A warrior takes care of his village, makes sure the old ones are taken care of, and that the children are safe.

But for the most part, it’s a comic book. There’s action and aliens, and weird stuff.

HCN Given all the injustices Native Americans have experienced, what keeps you fighting the good fight?

Proudstar To know I have that blood running through me definitely gives me strength. That’s what I’m hoping when kids pick up my book – that somewhere in there, they will find a window that opens up to them, too. We give kids the information in a non-threatening way. It’s not like a textbook.

HCN Is it intended to be controversial?

Proudstar The books that influenced me, like X-Men, were very controversial at the time, because they talked about homosexuality, racism, suicide – topics that were taboo in comic books. If an educator reads (Tribal Force), they definitely would be worried. (It has) a lot of violence and controversial subject matter.

But I’m not writing it for adults. I’m writing it for young people, in a medium they’re used to. It’s the art of “fighting without fighting.”

The last thing I want is teachers or organizations saying, “Children, you should read this.” If anything, I want them to say, “Stay away from this book.”