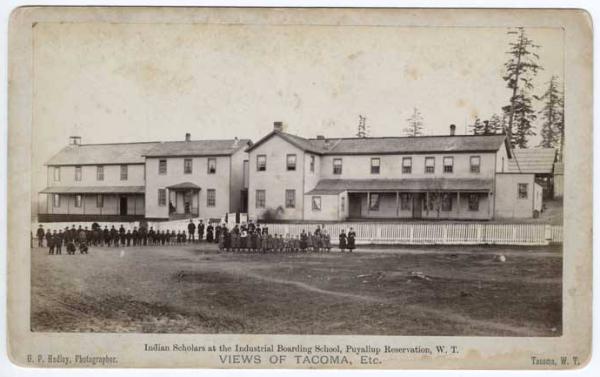

Starting in the middle of the 19th century, church groups and the U.S. government set up boarding schools for Natives. Here, children from many tribes were taught how to speak English and how to make a living. They were separated from their elders, and were discouraged from learning tribal traditions and language. This photo by U.P. Hadley shows the buildings and students at the Industrial Boarding School on the Puyallup Reservation between 1880 and 1889. The school opened in 1860. During the 1880s, a number of new buildings were added, and the school grew from 125 to about 200 students.

“If it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation,” Indian School Superintendent John B. Riley wrote in an 1886 reportto the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

“Only by complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents can he be satisfactorily educated.”

Such was the prevailing attitude of Indian Affairs agents during the federal boarding-school era: That America’s First Peoples were a problem to be dealt with, that America’s Manifest Destiny required Indigenous Peoples to be remolded and assimilated into the mainstream—even if it meant forcibly removing children from their families.

It wasn’t until 1978—118 years after the establishment of the first American Indian boarding school—that Native American parents gained the legal right, with the passing of the Indian Child Welfare Act, to deny their children’s placement in off-reservation schools.

“Some Native American parents saw boarding school education for what it was intended to be—the total destruction of Indian culture,” the American Indian Relief Council reported on its website. “Resentment of the boarding schools was most severe because the schools broke the most sacred and fundamental of all human ties, the parent-child bond.”

On October 12, council members in one of the largest cities in the U.S. took a step toward helping to heal the wounds from the boarding school era.

The City Council of Seattle, Washington, approved a resolution“acknowledging the various harms and ongoing historical and inter-generational traumas impacting American Indian, First Nations, and Alaskan Natives for the forcible removal of Indian children and subsequent abuse and neglect resulting from the United States’ American Indian Boarding School Policy during the 19th and 20th Centuries …”

The resolution calls on the United States to examine its human rights record and to work with American Indian and Alaskan Native peoples “in efforts of reconciliation in addressing the impacts of historical trauma, language and cultural loss, and alleged genocide.”

“The supposed goal [of the boarding schools] was to ‘Kill the Indian, save the man,’ which is tantamount to cultural genocide,” Seattle City Council member Kshama Sawant told LastRealIndians.com. “The resolution will give city officials the opportunity to acknowledge and help heal the deep wounds opened up by the boarding school policy. It is also another step toward getting the city to take real action to address the poverty, oppression, and marginalization that the community faces to this day.”

The resolution was drafted by Matt Remle, Lakota, with support from Seattle lawyer Gabe Galanda, Round Valley Indian Tribes; Seattle Arts Commissioner Tracy Rector, Seminole; the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition; the Native American Rights Fund, and other members of Seattle’s Native community. The resolution was sponsored legislatively by Sawant.

The resolution vote took place on Seattle’s second annual Indigenous Peoples’ Day. The day included a rally and march to Seattle City Hall, drumming and songs, a keynote address by Winona LaDuke, Ojibwe, and a celebration at Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center.

During the boarding school era, “roughly 100,000 American Indian children ages 5-18 were stripped from their homes and placed in remote boarding schools,” Remle wrote on LastRealIndians.com. “Native languages, spirituality and customs were outlawed, physical and sexual violence was rampant.”

It’s a subject known all too well by the First Peoples of the Seattle area. Seattle, named for the mid-1800s leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples, is the largest city in a state with 29 federally recognized Native nations. The first American Indian boarding school in the United States was established at the Yakama Nation in eastern Washington in 1860; the Tulalip Mission School, operated by the Catholic Church, was established three years earlier and was the first contract school for Native American children.

In her book, Tulalip, From My Heart, Harriette Shelton Dover (1904-1991) wrote of harsh discipline, poor diet and inadequate care, of tuberculosis and pneumonia and childhood deaths.

RELATED: From the Heart: Tulalip History and Memoir Is a Walk Back in Time

Helma Ward, Makah, told Carolyn J. Marr, an anthropologist and photographs librarian at the Museum of History and Industryin Seattle, “Two of our girls ran away … but they got caught. They tied their legs up, tied their hands behind their backs, put them in the middle of the hallway so that if they fell, fell asleep or something, the matron would hear them and she’d get out there and whip them and make them stand up again.”

“They were not allowed to speak their language there,” Inez Bill, Tulalip, told KING 5 News, Seattle, of her grandparents’ boarding school experience. “When you lose your language, you lose your culture. It left our people scarred.”

Fast forward to today: The children and grandchildren of those who were forced to attend boarding schools and were banned from speaking their languages have taken control of their own children’s education, are showing that their culture has an important role in education and that it can build bridges of understanding in communities.

Almost 65,000 students in Washington identify as Native American or Alaskan Native, according to the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. OSPI’s Office of Native Education was created in the mid-1960s to help Native students achieve their education goals and meet state standards. The office provides resources and training to help educators and families meet the needs of Native students, builds curriculum in Native languages and about Native culture and history, and works to increase the number of Native educators.

Eight Native nations operate their own schools in Washington, according to the state Superintendent of Public Instruction. School districts near reservations have liaisons to the Native American community and/or partnerships with a local Native nation’s education department. Earlier this year, the state legislature mandated the inclusion of Native American history, culture and governance in the curriculum of local public schools.

During its heyday, the American Indian Heritage Early College High School in Seattle had a 100 percent graduation rate, and all graduates went on to college. The Urban Native Education Alliance is lobbying to have the school reestablished in the new Robert Eagle Staff Middle School, named for the late principal of Indian Heritage and under construction at the site of the former school.

The Suquamish Tribe operates and funds Chief Kitsap Academy, a high-tech, culturally based high school that is part of the Early College High School network. According to the state Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, only four of 10 of North Kitsap School District schools and programs met Adequate Yearly Progress goals in reading and math proficiency in 2014—one of those was Chief Kitsap Academy. Students use the latest technology, but are also exposed to cultural teachings and study the Lushootseed language. The school is open to Native and non-Native students.

Northwest Indian Collegehas grown from a school of aquaculture to a four-year college with six satellite campuses in two states. It offers four undergraduate degrees, nine associate’s degrees, three certificate programs, and five other study programs. The University of Washingtonand The Evergreen State Collegehave longhouses that serve as places of gathering and sharing as well as teaching.

Eaonhawinon Patricia Allen, a University of Washington graduate and community organizer in Seattle, spoke at Seattle City Hall before the City Council’s vote. She later wrote on LastRealIndians.comthat the boarding school era “was one of the last actions made to complete colonization and … to wash the Native identity out of Natives. But I am here to tell you this, and so will my future children: We still survived and are starting the process of healing.”

Canada established a Truth and Reconciliation Commissionto prepare a complete historical record on the policies and operations of residential schools; complete a public report, including recommendations to the parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement; and establish a national research center that will be a lasting resource about the Indian Residential Schools legacy in Canada. The commission is reaching out to the public in national and community events, and honoring residential schools survivors in a lasting manner. It is also examining the number and cause of deaths, illnesses, and disappearances of children, and documenting the location of burial sites.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/10/20/seattle-continues-healing-deep-wounds-boarding-school-resolution-162138