Source: The Herald

For kids — and kids at heart: Families can see and touch emergency vehicles including police, fire, public works and other emergency and utility vehicles at Touch-a-Truck. The event is from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturday at the Rosehill Community Center Upper Parking Lot, 304 Lincoln Ave., Mukilteo. There will be arts and crafts and games for kids. Event takes place rain or shine. More info: call 425-263-8180.

Tour farms: Visit farms on a self-guided tour on Saturday and Sunday. The Port Susan Spring Jubilee Farm Tour is 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday and 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Sunday. Get all the details in our story here.

Plant a gift for Mom: Children can plant pots with flowers for Mother’s Day gifts with the help of Edmonds in Bloom volunteers, 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. Saturday at the Edmonds Farmer’s Market, Fifth Avenue North and Bell Street. Suggested donation is $9. Also, a Children’s Fairy Flower Parade starts at noon at the Edmonds Library, 650 Main St. For more information, check www.edmondsinbloom.com.

Take Mom sailing: A free Mother’s Day Sail is Saturday at The Center for Wooden Boats at Cama Beach State Park. There are classic wooden boats to see, and for kids, a chance to build toy boats, using hand tools and wooden hulls from scrap wood. The event is from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. at Cama Beach State Park, 1880 SW Camano Drive, Camano Island. More info here.

“Rapunzel”: See the story on stage, in a show best for ages 3 to 10. The shows are at 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. Sunday at Snohomish County PUD, 2320 California St., Everett. Tickets are $10. For more information, go to www.storybooktheater.org.

For bird lovers: International Migratory Bird Day is Saturday and the Pilchuck Audubon Society is planning a host of events throughout Snohomish County. All events are free and families are welcome. A variety of field trips, walks and classes are offered. Check our story here for all the details.

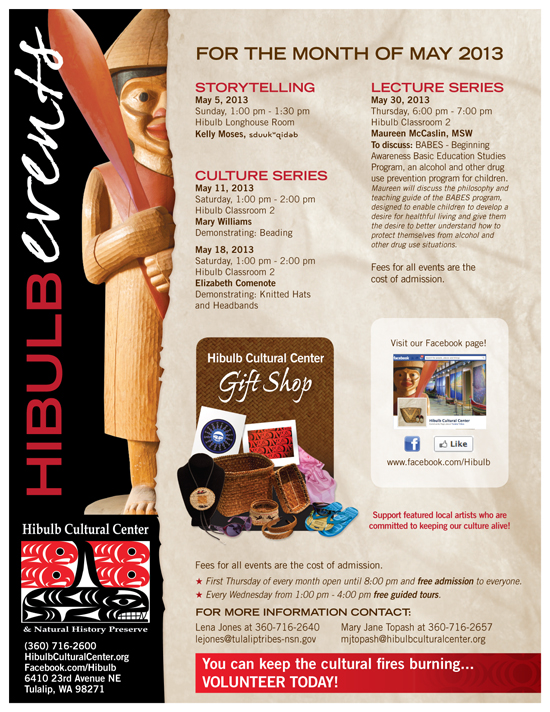

Hibulb powwow: The 21st annual Hibulb Powwow is at Everett Community College on Saturday. The event features traditional American Indian dancing, drumming, singing and arts and crafts. Grand entries are at 1 and 6 p.m. Find more details in our story here.

Meet parrots: Kids can see live parrots and learn about their habitats in the wild and keeping them as pets. The event is for preschoolers and older. The event is at 11 a.m. Saturday at the Evergreen branch of the Everett Public Library and at 2 p.m. Saturday at the main branch of the library. Find more information here.

National Train Day: The Swamp Creek and Western Railroad Association plans an open house, 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Saturday at 210 Railroad Ave., Edmonds. The SC&W has been located in the Edmonds Amtrak Station since 1977 and features more than 400 feet of HO scale track as model trains operate through a scenic layout. More info: 425-257-9343.

Bake and plant sale: The Camano Animal Shelter Association plans a bake sale and plant sale fundraiser, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday at the Camano Multi-Purpose Center, 141 East Camano Drive. Stop by for hot dogs, water and free coffee and shop for delicious desserts and indoor and outdoor plants. More info: www.camanoanimalshelter.org or 360-387-1902.

Nature fair: The Watershed Fun Fair is from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday at Yost Park, 9535 Bowdoin Way, Edmonds. The fair will feature guided nature walks, nature crafts and activities especially for kids. The event features exhibits and information about Puget Sound stewardship, stormwater, fish and wildlife, backyard habitat, recycling, energy and water conservation.

Wine walk: A wine walk with thrift store gift shop bargains is from 4 to 7:30 Friday night in Snohomish. Click here for more details.

Free for moms: In honor of Mother’s Day, admission is free for all moms at Imagine Childrens Museum in Everett on Sunday.

Amazing acrobatics: Watch acrobats leaping between tall poles, contortionists, flexible performers doing handstands on high human pyramids and stacked chairs 20 feet high at Cirque Zuma Zuma on Sunday at Comcast Arena. Read our story here for the details.

For art lovers: The Camano Island Studio Tour, featuring 48 professional and amateur artists, 34 studios and three galleries, kicks off its 15th anniversary year this weekend. A tour runs Saturday and Sunday, and next weekend also. Get the details in our story here.

In honor of strong women: The town of Langley is putting on a celebration this weekend that pays tribute to strong women of the past and today’s mothers and daughters. On Saturday, women suffragettes will march at 11 a.m. in downtown Langley, followed by street theater to celebrate those who fought for women’s right to vote. For more information, call 360-929-9333 or go to www.mainstreetlangley.org.