By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

“We are all thankful to our Mother, the Earth, for she gives us all that we need for life.” – Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address.

Perspective

Each November families across the country teach their children about the First Thanksgiving, a classic American holiday. They try to give children an accurate picture of what happened in Plymouth in 1621 and explain how that event fits into American history. Unfortunately, many teaching materials give an incomplete, if not completely inaccurate, portrayal of the first Thanksgiving, particularly of the event’s Native American participants.

Most texts and supplementary materials portray Native Americans at the gatherings as supporting players. They are depicted as nameless, faceless, generic “Indians” who merely shared a meal with the valiant Pilgrims. The real story is much deeper, richer, and more nuanced. The “Indians” in attendance, the Wampanoag, played a lead role in the historic encounter, and they had been vital to the survival of the colonists during the newcomers’ first year.

The Teachers

The Wampanoag were a people with a sophisticated society who had occupied the region for thousands of years. They had their own government, their own spiritual and philosophical beliefs, their own knowledge system, and their own culture. They were also a people for whom giving thanks was a part of daily life.

The Wampanoag people have long lived in the area around Cape Cod, in present-day Massachusetts. When the English decided to establish a colony there in the 1600s, the Wampanoag already had a deep understanding of their environment. They maintained a reciprocal relationship with the world around them. As successful hunters, farmers, and fishermen who shared their foods and techniques, they helped the colonists adapt and survive in “the new world”.

Wherever Europeans set foot in the Western Hemisphere, they encountered Native peoples who had similar longstanding relationships with the natural world. With extensive knowledge of their local environments, Native peoples developed philosophies about those places based on deeply rooted traditions.

The ability to live in harmony with the natural world begins with knowing how nature functions. After many generations of observation and experience, Native peoples were intimately familiar with weather patterns, animal behaviors, and the cycles of plant, water supply, and the seasons. They studied the stars, named constellations, and knew when solstices and equinoxes occurred. This kind of knowledge enabled Native peoples to flourish and to hunt, gather, or cultivate the foods they needed, even in the harshest environments.

Traditionally, Native peoples have always been caretakers in a mutual relationship with their environment. This means respecting nature’s gifts by taking only what is necessary and making good use of everything that is harvested. This helps ensure that natural resources, including foods, will be sustainable for the future. In this way of thinking, the Wampanoag along with every other Native tribe believe people should live in a state of balance within the universe.

Native communities throughout the Americas have numerous practices that connect them to the places where they live. They acknowledge the environment and its gifts of food with many kind of ceremonies, songs, prayers, and dances. Such cultural expressions help people to maintain the reciprocal relationship with the natural world. For example, the Tulalip Tribes of Washington conducts a special ceremony every year called Salmon Ceremony that demonstrates respect for the life-sustaining salmon as a gift. By properly respecting the fish, the Salmon King will continue his benevolence through months of salmon returns.

The Immigrants

A majority of those who came to America on the Mayflower came to make a profit from the products of the land, the rest were religious dissenters who fled their own country to escape religious intolerance. The little band of religious refugees and entrepreneurs that arrived on the Mayflower that December of 1620 was poorly prepared to survive in their new environment. They did not bring enough food, and they arrived too late to plant any crops. They were not familiar with the area and lacked the knowledge, tools, and experience, to effectively utilize the bounty of nature that surrounded them. For the first several months, two or three died each day from scurvy, lack of adequate shelter, and poor nutrition. On one exploration trip, the immigrants found a storage pit and stole the corn that a Wampanoag family had set aside for the next season.

As the starving time of the European’s first winter turned to spring, the Wampanoag began to teach them how to survive within their lands. The summer passed and the newcomers learned to plan and care for native crops, to hunt and fish, and to do all the things necessary to partake of the natural abundance of the earth in this particular place. All of this occurred under the watchful instruction and guidance of the Wampanoag.

A Harvest Celebration

As a result of all the help and teachings the Europeans received from the local Wampanoag, they overcame their inexperience and – by the fall of their first year in Wampanoag country, 1621 – they achieved a successful harvest, mostly comprised of corn. They decided to celebrate their success with a harvest festival, mimicking that of the Harvest Home they would have most likely celebrated as children in Europe.

Harvest Home was traditionally held on the Saturday or Sunday nearest to the Harvest Moon, the full moon that occurs closes to the autumn equinox. It was typically held in parts of England, Ireland, Scotland, and northern Europe. The Harvest Home consisted of non-stop feasting and drinking, sporting events, and parading in the fields shooting off muskets.

The “First Thanksgiving” is said to be based on customs that the Europeans brought with them. Even though from ancient times Native people have held ceremonies to give thanks for successful harvests, for the hope of a good growing season in the early spring, and for good fortune. Traditional Wampanoag foods such as wild duck, goose, and turkey were main dishes of the menu.

Although the relatively peaceful relations first established were often strained by dishonest, aggressive, and brutal actions on the part of the “settlers”, the Wampanoag were gracious hosts to their now immigrant neighbors. Edward Winslow (a European attendant at the celebration) stated in a letter from 1621 that the harvest celebration went on for three days and was highlighted by the Wampanoag killing five deer, thus providing the feast with venison.

Afterward

In only a matter of years following the harvest celebration that would become known as the “First Thanksgiving”, the rarely achieved, temporary state of coexistence had been torn to shreds. The great migration of European refugees and religious zealots to America that ensued brought persecution and death to the Native tribes. Full-scale war erupted in 1637 and again in 1675, ending with the defeat of the Wampanoag by the English. Though decimated by European diseases and defeated in war, the Wampanoag continued to survive through further colonization in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. Today, the Wampanoag live within their ancestral homelands and still sustain themselves as their ancestors did by hunting, fishing, gardening, and gathering. Additionally, they maintain a rich and vital oral history and connection to the land.

Sharing agricultural knowledge was one aspect of early Native efforts to live side by side with Europeans. So, the “First Thanksgiving” was just the beginning of a long, brutal history of interaction between Native peoples and the European immigrants. It was not a single event that can easily be recreated. The meal that is ingrained in the American consciousness represents much more than a simple harvest celebration. It was a turning point in history.

Present-day

Giving daily thanks for nature’s gifts has always been an important way of living for traditional Native peoples. Ultimately, Native peoples’ connection to place is about more than simply caring for the environment. That connection has been maintained through generations of observations, in which people developed environmental knowledge and philosophies. People took actions to ensure the long-term sustainability of their communities and the environment, with which they shared a reciprocal relationship. In their efforts, environmentalists are acknowledging the benefits of traditionally indigenous ways of knowing. Today, Native knowledge can be a key to understanding and solving some of our world’s most pressing problems.

Did you know?

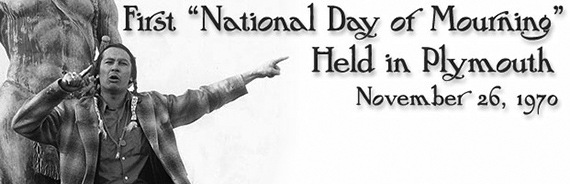

National Day of Mourning

An annual tradition since 1970, Native Americans have gathered at noon on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts to commemorate a National Day of Mourning on the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday. Many Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers. To them, Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture. Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression which Native Americans continue to experience.

The following is an excerpt from a speech given by Moonanum James, Co-Leader of United American Indians of New England, at the 29th National Day of Mourning.

“Some ask us: Will you ever stop protesting? Some day we will stop protesting. We will stop protesting when the merchants of Plymouth are no longer making millions of dollars off the blood of our slaughtered ancestors. We will stop protesting when we can act as sovereign nations on our own land without the interference of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and what Sitting Bull called the “favorite ration chiefs”. When corporations stop polluting our mother, the earth. When racism has been eradicated. When the oppression of Two-Spirited people is a thing of the past. We will stop protesting when homeless people have homes and no child goes to bed hungry. When police brutality no longer exists in communities of color. Until then, the struggle will continue.”

Sources:

- American Indian Perspectives on Thanksgiving. National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved from www.si.edu

- Harvest Ceremony. Johanna Gorelick and Genevieve Simermeyer, the Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved from www.socialstudies.org

- National Day of Mourning (United States protest). Retrieved from www.wikipedia.org