By George Plaven, East Oregonian, Source: OPB

A new microbattery no larger than a long grain of rice could help biologists track the movement of younger, smaller fish through Northwest rivers.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland developed the tiny battery to power transmitters placed in juvenile salmon and steelhead, monitoring the fish at earlier stages in their life cycle.

By studying how subyearling chinook behave and migrate down the Columbia River, federal managers can make better decisions to improve overall habitat and survival. The challenge is creating smaller tags for smaller fish, which take smaller batteries that still pack enough of a charge to work.

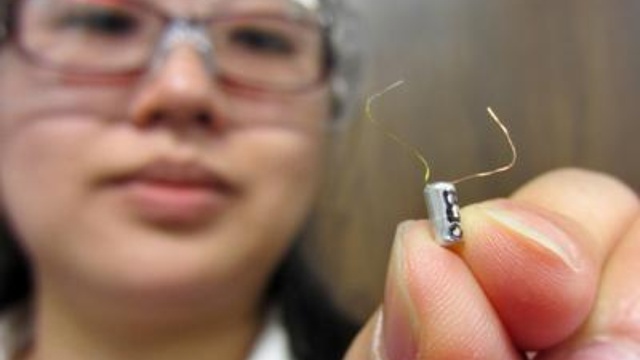

PNNL now believes it has the answer. Its battery, at 6 millimeters long and 3 millimeters wide, isn’t the smallest ever created but packs twice the energy compared to current microbatteries, according to the lab’s findings.

That’s enough power for acoustic fish tags to broadcast signals every three seconds for about three weeks, or about every five seconds for a month. It’s also teeny enough to inject into fish using a hypodermic needle, as opposed to surgically implanting the transmitter, which is more expensive and stressful for the fish.

Brad Eppard, fisheries biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Portland, said battery size was the biggest obstacle to tracking such small juvenile salmon. This microbattery not only clears that hurdle, but essentially revolutionizes the market, he said. “We have a pretty good tool here,” Eppard said. “It helps us to better understand what’s happening when (the fish) are migrating.”

The Corps was first required to study subyearling fall chinook salmon based on a 2001 biological opinion by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the Columbia River hydroelectric system. Researchers launched the Juvenile Salmon Acoustic Telemetry System, or JSATS, developing tags for the young fish.

It took five years to get their first functioning transmitter, Eppard said. In 2010, the Corps turned to PNNL to create an even smaller, injectable device. Lab engineer Daniel Deng called on Jie Xiao, a materials science expert, to come up with the battery design.

Xiao and her team ultimately perfected a painstaking process that involved cutting snippets of battery material, running them through a flattening device and stacking them on top of each other in layers. Each battery is then rolled by hand with tweezers — like a jellyroll — and inserted into an aluminum container.

“It was pretty difficult in the beginning,” Xiao said. “Once you learn how, as well as all the tricks, it becomes very standard protocol.”

Samuel Cartmell and Terence Lozano, scientists in Xiao’s lab, hand-rolled more than 1,000 of the batteries last summer. A PNNL team led by Deng then surgically implanted 700 of the tags into salmon in a field trial at the Snake River, where preliminary results show the technology worked exceedingly well. More details about the experiment will be released in a later publication, according to PNNL. Xiao said she has high hopes for developing the tags, as well as other uses for the microbattery. Battelle Memorial Institute, which operates PNNL, has applied for a patent. “There is a lot of opportunity,” she said.