Blown glass. Preston Singletary (Tlingit).

Singletary worked at Pilchuck Glass School, an international center for glass art education, for thirteen years where he studied with Dale Chihuly. His work is renowned for incorporating Northwest Coast design into the non-traditional medium of glass, synthesizing his Tlingit cultural heritage, modern art, and glass into a unique blend all his own.

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

Fused and sand carved glass. Preston Singletary (Tlingit).

Growing up in west coast cities and trained in European glass techniques and practice, Singletary began incorporating Native iconography into his work in 1987, explaining: “I found a source of strength and power in Tlingit designs that brought me back to my family, society, and cultural roots.” In this, his first monumental work, the artist studied the house screen and fused his clan’s Killer Whale crest into sixteen panels. Thus recharging an ancient tradition and bringing the past forward.

Traditional teachings spanning countless generations and highly detailed craftsmanship are imbedded within the foundation of Native American artwork. These fundamental aspects continue today much as they did thousands of years ago, even as today’s Native artists continue to evolve in response to social changes, new markets, and a desire for unique, personal expression.

The resurgence of canoe carving teaches youth how to strengthen body and spirt by working together, while increasing importance on tribal food sovereignty assists healers combat modern diseases in a traditional way. Like so many aspects of their vibrant culture, Native artists have an important dual role of simultaneously creating works for their family and community celebrations, but also for public consumption via private sales, art galleries and educational displays.

Think of how far Indigenous representation in the greater Seattle area has come in just the last several decades. Thirty years ago, you couldn’t find a map using the term ‘Salish Sea’ for the Puget Sound region. Present day, the term ‘Salish’ is a part of local vernacular and commonly understood as describing tribal culture spanning the Northwest Coast.

Through the efforts of many, a vision of authentically produced flowing formline to represent its homelands has come to fruition. The characteristic sweeping lines and subtle patterns of Salish art is now recognizable and emblematic of the Northwest Coast, as it was always meant to be.

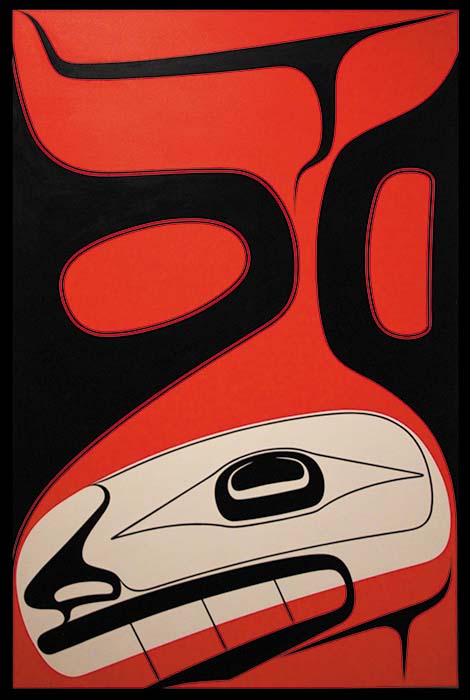

Acrylic on canvas. Robert Davidson (Haida).

According to Haida oral traditions, Canoe Breaker is one of ten brothers of Southeast Wind, who is responsible for the turbulent weather on Haida Gwaii. “In the form of a killer whale, the white ovoid actually separates the lower teeth from the upper teeth in the mouth. And the top shape would be the tail and this U-shape could be the pectoral fin and dorsal fin. When we see the killer whale in their world, we being to understand them, so that’s why human attributes are often mixed in with what they look like.”

We bring you now a collection of Indigenous artistry that evokes traditional ties to the land and sea, while showcasing innovation and a look to the future. Today’s artists aren’t afraid to push boundaries nor experiment with non-traditional materials. Instead, they welcome the challenge to display the beauty of Salish culture across all mediums.

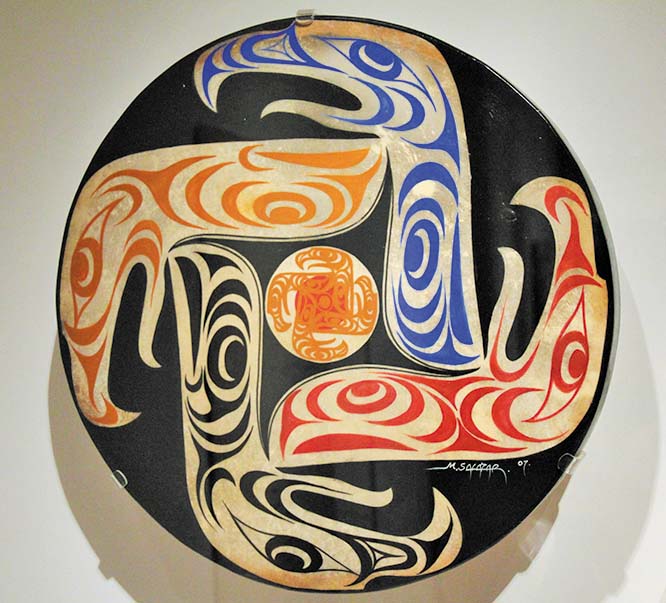

Eagle and Salmon, 2007.

Deer hide, acrylic paint. Manuel Salazar (Cowichan).

Wood, paint, feathers, rabbit fur, cloth. Calvin Hunt (Kwagu’l).

“In our culture, we believe the animals and the birds can take off their cloaks and transform into human beings.” Spectacular, articulated dance masks are the specialty of Indigenous artists who craft the elaborate regalia worn in the dance-dramas depicting mythic events and deeds of ancestors. They transport the viewer to a time when spirits and humans interacted, as represented by this mask, in which the Thunderbird transforms into a human.

Five boxes digitally printed on Fome-cor. Sonny Assu (Southern Kwakwaka’wakw).

Breakfast Series appropriates the form of the familiar cereal box and decorates its surfaces with commentary on highly-charged issues for Indigenous people – such as the environment, treaty rights and land claims. The pop art-inspired graphics on the five boxes in the series contain recognizable imagery, but upon closer inspection we see that Tony the Tiger is composed of formline design elements, the box of Lucky Beads includes a free plot of land in every box, and contains “12 essential lies and deceptions.” The lighthearted presentation, upon further investigation, exposes serious social issues.