By Shaelyn Smead, Tulalip News

The June 24 Supreme Court overturn of Roe v. Wade has taken over recent political discussions, and people are taking a deep dive into its origins, and a closer look at how it affects minority communities.

A decision that was once determined in 1973, has now changed so many factors around women’s reproductive systems and healthcare in 2022, and many women are left in disarray. Protest efforts focused on feminist, civil rights, and anti-government movements that people in America fought hard for in the ‘70s, also opened up another level of importance for tribal communities.

It is no surprise that the history between natives and the American government and the control they’ve had over tribal communities have had negative outcomes. In 1851, Native Americans were forced onto reservations, shortly after executive orders and agreements established federal responsibility for the provision of healthcare for tribal members. For decades, natives struggled with poverty, and as a biproduct, depended on government organizations like the Indian Health Service (IHS), Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). This forced dependence on government organizations gatewayed towards a major population decline in tribal communities, and a new rise in government abuse towards Native American women.

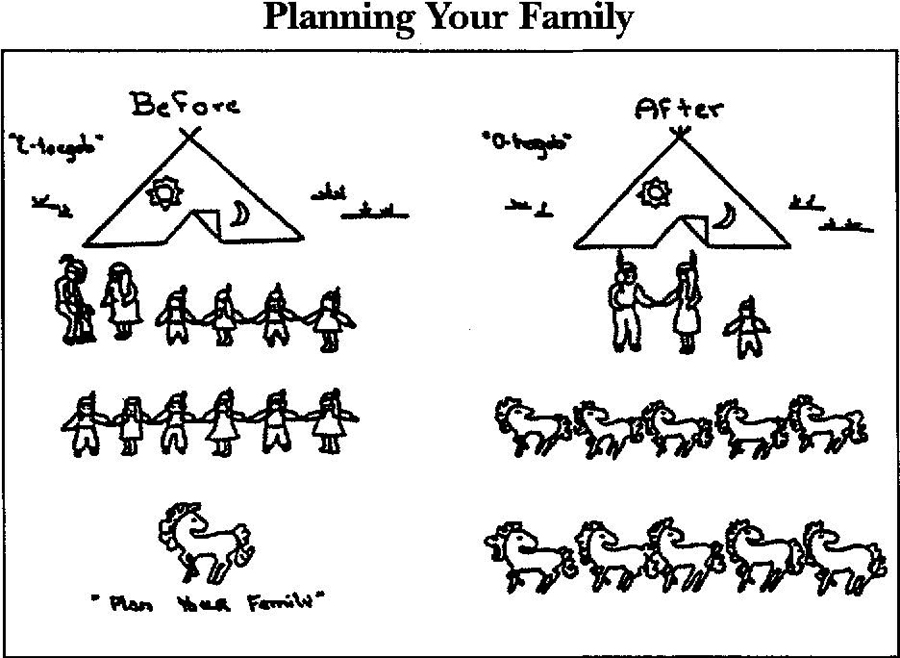

In an attempt for population control in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the IHS and participating doctors begin performing sterilizations on Native American women. These horrific attempts were made to diminish the amount of government supported households within tribal communities. The physicians even went as far as saying that it would ‘improve Native American’s financial situation and their family’s quality of life’. And by targeting the communities that most regularly applied for Medicaid and Welfare, the federal government could decrease their spending on welfare programs.

The two main sterilization methods included Hysterectomies and Tubal Ligation. A hysterectomy is a procedure used to remove the uterus. Tubal ligation is a procedure in which a woman’s fallopian tubes are tied, blocked, or cut. In some of these procedures, Native American women were led to believe that the procedure was somehow reversible. And in most of these practices, it was believed to be performed without adequate understanding and patient’s consent. Meaning that the patient either had no idea that the procedure was taking place, or the procedure was presented as something it wasn’t. Because of this apathetic mentality towards Native American communities, these procedures were even administered to natives as young as 11 years old.

Tribal dependence through the IHS, the HEW, and the BIA robbed native women of the children they could have had, and jeopardized future generation existence. According to the American Indian Culture and Research Journal, the HEW funded 90% of the annual sterilization costs for poor people. Since then, a multitude of native organizations have since came forward and accused these government organizations for committing these heinous acts on approximately 25%-40% of Native American women of childbearing age. Sadly, this violation of our human rights was powerful, and according to the US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, the average birth rate of Native American women being 3.29 in the ‘70s quickly fell to 1.3 in the ‘80s.

Native American communities lost economic and political power by not being able to reproduce at the same rate as their white counterparts. There is power in numbers, and less of a native population meant less efforts and votes towards Native American rights. These monstrous acts also increased the risk of extinction of the Native American people and our culture that embodies us.

It wasn’t until 1973-1976 when the Government Accountability Office (GAO) began doing research and investigating the numbers of Native American sterilizations and found that IHS’ four out of the twelve areas that they studied were noncompliant with the policies regulating consent to sterilization. The GAO study, involved Albuquerque, Phoenix, Oklahoma City, and Aberdeen, South Dakota. The number of sterilizations would’ve been comparable to 452,000 non-native women. Even though the other eight IHS areas were not studied, it was enough for the GOA to understand what a major setback this was for native women.

Although Latinas, African-Americans, and Native Americans all suffered tremendously during this time, natives were easier targets because of their social invisibility, smaller numbers, and laws that were already instated working against them. It took many years of constant pressure from women and minorities in America, news reports, hearings, and efforts put forth by tribal communities, where the light was finally shined on forced sterilizations. Eventually new federal regulations were adapted, and new acts like the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978, instilled more protection over native families from the American government.

In addition to Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn McGirt v. Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, has created new risks for tribal sovereignty. These specific decisions continue to act as possible stepping stones that blur the lines between the American government and native women’s reproductive systems. Such a grey area, that it threatens the idea of a world that our people once knew and were forced to endure.

The Tulalip Community Health Department released a statement on the issue saying, “In light of today’s ruling to overturn Roe vs Wade: please know that Tulalip community health will continue to support each personal decision of their reproductive health. We are a safe place to ask questions and reach out for help.”

If history as Native Americans in the US has taught us anything, it is how important it is to continue to protect ourselves, our community, and our future. We have to get more involved, and continue to have a voice.