“The months our Snohomish ancestors knew are vastly different than the ones we know now. Our seasons were moons. These moons were named after the environment or ecosystem and what was able to be harvested during that time. This was the Snohomish people’s way of staying connected to the earth. The earth would provide for them if they took proper care of it. This meant not overharvesting fish or vegetation but leaving enough for the wildlife living beside them as well as future generations.”

– Sarah Miller, Lushootseed Language Warrior

By Kalvin Valdillez

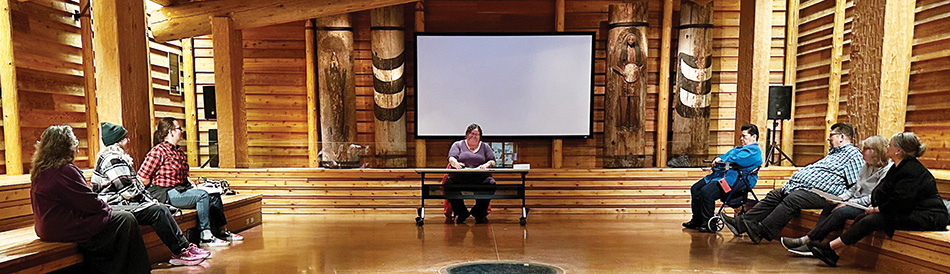

On a rainy and dark afternoon, close to thirty people gathered in the longhouse of the Hibulb Cultural Center. With the lights dim low, the group of locals took their seats on either side of the room constructed entirely of cedar. At the front and center of the longhouse, sat Lushootseed Warrior Sarah Miller, fittingly positioned in between four cedar carved story poles. Aided by the relaxing sound of rain hitting the rooftop, Sarah’s natural storytelling ability transported each individual to a time well before the colonization of America, a time where the lifeways of the sduhubš revolved around 13 moon cycles.

After we recently welcomed a new year in the Gregorian calendar, many were excited to learn about how Tulalip’s ancestors observed the concept of time pre-contact. Like most Salish tribes and other Indigenous nations, the sduhubš marked the time of year not only based on weather changes but also by their connection to the natural world.

Through the traditional story, Star Child and Diaper Child, Sarah introduced the crowd to two important figures to the sduhubš people, the sun and moon. In the Tribe’s ancestral language, the two were known as dukʷibəɬ.

She explains, “Together, the sun and moon became dukʷibəɬ; the Changer, the Transformer, or the Creator. The Changer was responsible for making the world what it is today. dukʷibəɬ changed animals from what they were to what they are. Before the change, animals talked, walked, and worked similar to humans. dukʷibəɬ also changed humans from what they were to what they are now. Before the change, humans had the ability to morph into different animals, usually their spirit power animals. dukʷibəɬ walked this land, from the east to the west and changed everything. Changer was also responsible for giving all the tribes their different languages. Changer was responsible for naming everything. The Changer was our Creator.”

During Sarah’s hour-long lecture she captivated her audience by sharing the traditions of her ancestors, many of which are still celebrated and practiced today, such as the Salmon Ceremony and the harvest of salal berries.

With the amount of time and research Sarah put into this presentation, we urge you to attend her lecture in full, as well as any of the Lushootseed workshops that are often held at Hibulb Cultural Center throughout the year. For this publication, we are going to share the thirteen months with you, led by excerpts from Sarah’s lecture.

ƛ̕iq̓s – The time when your stomach sticks to your backbone (January)

The January moon, one of our winter moons, was called ƛ̕iq̓s. In Lushootseed, this meant as period of time when your stomach sticks to your backbone. This is because in the wintertime, food is scarce.

During this cold time, the people relied on whatever food they had gathered and stored in prior months.

səxʷpupuhigʷəd – The time of the blowing winds (February)

Once the winds picked up through the area, it was səxʷpupuhigʷəd, which means the time of the blowing winds. During this moon, the area would experience a lot of wind. Food was still kind of scarce, but the wind blew the biting cold around.

Since these winter moons were scarce of food, a lot of people would fast and quest for their spirit powers. Some people would go out into the forest, away from their villages to find their power. They would bathe in icy cold rivers and lakes.

The Snohomish people would participate in ceremonies of the smokehouse faith; drumming, singing, and dancing to bring out their power. A long time ago, it was said that during the winter months, the physical world was closer to the spiritual world, which is why singing, dancing, and drumming took place.

waq̓waq̓us – The time of the singing frogs (March)

Once the frogs started singing en masse, it signified a new moon or month was starting. Smokehouse ceremonies stopped and it was time to go out into the woods and check on what was starting to bloom. By this point, the winds would start to die down and the earth was warming up a bit.

As springtime continued to arrive, there would be many things for the Snohomish people to do, such as prepare to move from their winter villages to their summer ones.

Back in those days, the longhouses were put up in a way that they could be disassembled and reassembled as needed. The winter locations were near bodies of water, but also close to forests for hunting purposes. The summer locations were located near clam beds or accustomed fishing grounds. In the summer, longhouses were erected that also could house many people, however, a lot of times the Snohomish people utilized smaller mat houses, especially when fishing at the river or near the bay.

Slihibus −The time of the cranes (April)

During this time, you’d hear the songs of cranes and swans as they started their migration. At this time, the earth is getting warmer, and more foods are coming into season. Game might be a little more available. The Snohomish people would journey to the Holmes Harbor area to fish for smelt and herring.

Throughout these seasons potlatches would be held. A potlatch could be held for any reason such as a wedding, a funeral, births, or even winning a dispute against a warring tribe was a call for celebration.

pədx̌ʷiw̓aac – The time of the whistling robins (13th Moon)

This month is considered the missing month, or the thirteenth month, because it does not appear in the Lushootseed calendar that we know and use today. In order to fit with the Gregorian calendar, this moon was omitted.

pədx̌ʷiw̓aac means the time of the whistling robins. After the cranes and swans had migrated, the robins would start in with their singing.

While Harriette Shelton said this moon was the time of the whistling robins, her father, William Shelton called it sɬukʷaləb, which means, “little moon.” This isn’t too far off from the word commonly used for moon, which is sɬukʷalb. Perhaps Harriette and William were talking about two different moons, but maybe that they were talking about the same moon. Whatever the reason, this is technically not even the thirteenth moon; it’s the fifth of the Snohomish people. There is no information on why this month specifically was chosen to be taken out of the calendar.

pədč̓aʔəb − The time for digging up roots (May)

During this month we start digging up roots. Camas was a popular root amongst the Snohomish. Camas root has beautiful purple blooms but is more akin to being a small onion, though sweet. At this point, most people might have packed up and started heading towards their summer homes.

Nettles were also harvested and used in soups and for various other medicinal needs. Cattail was harvested as well. Snohomish people mostly used them to make mats with. The natives would split some of the shoots and peel layers of them out to weave with. The cattail mat was said to be comfortable to lay on, especially if you piled several of them up. When I talk about mat houses, this is what they were made of. There was a frame or structure made of planks taken from the bigger longhouses and they were covered with many cattail mats to make a little house.

Horsetail was also harvested during this month, it was a good herb to remedy ulcers, wounds, and even kidney problems. Ferns were also harvested. Bracken fern, licorice fern, maidenhair fern, and sword fern were good medicinal ferns. Bracken could be used as a tonic, licorice helped with colds and sore throats, maidenhair helped the respiratory system and sword fern could be used to treat skin sores.

pədstəgʷad – The time of the salmonberries (June)

The next few months are known as the berry months, because of the different berries that grow during the summer. June is known as pədstəgʷad, or the time of the salmonberries. This month typically lasts from May to late June. By now, the Snohomish people were living at their summer village sites, either in summer longhouses or mat houses.

This month also began the run of King Salmon, or hikʷ siʔab yubəč. The first king would be caught and celebrated in ceremony. There would be songs and dances to welcome the hikʷ siʔab yubəč and its return to the waters.

During these moons, the days were getting longer. There was more time to gather roots, gather chutes, gather berries, gather shellfish, and troll for fish. In the evening, people joined together in the longhouses to share stories and songs. Sometimes there was a potlatch, a wedding, a funeral, or a birth. Sometimes, there was no special occasion. It was just enjoying the full moon with your village.

pədgʷədbixʷ − The time of the blackberries (July)

The blackberries would bloom during part of July. Once the stəgʷad stopped bearing fruit, it was time for the blackberry bushes to bear fruit. Blackberries would start blooming in July, but they wouldn’t officially be ready to gather until about August.

Blackberries were good for flavoring soups but could also be used to dye wool or cedar darker colors. Tea could be made from the leaves of the blackberry vine. Blackberry leaf tea could help with illnesses and was also said to be good for the skin.

In addition to harvesting berries, clams were also harvested. After a morning of harvesting clams, someone would start a fire and the clams would be cooked amongst the hot rocks, right on the beach.

pədt̕aqa − The time of the salal berries (August)

These delicious purple berries ripen during this moon and not only are they good to eat, but they are also medicinal. These berries are a deep purple color, which is where we get the Lushootseed word for purple: t̕aqahalus.

In addition to being a good source of food, these were also a good medicine for the Snohomish people. They helped with colic and diarrhea but also cuts, burns and respiratory illnesses such as colds and tuberculosis.

Our ancestors had a unique way of storing not only t̕aqa but other berries as well to make them last well beyond their harvesting season. Our ancestors used to eat the berries in soups and with salmon or other meals.

pədkʷəxʷic − The time of silver salmon’s return (September)

September in Lushootseed is pədkʷəxʷic, or the time of the return of the silver salmon. Now, this doesn’t refer to the entire month of September but rather, just the length of time that the silver salmon run. Our ancestors would get into their canoes and along with their tools, go trolling for fish. Each fisherman knew how much strain their line could take. If they were to catch large fish, they knew how to carefully bring them up to the side of the canoe, where they would then spear the fish with a harpoon and put them in the canoe. The harpoon was usually made of ironwood.

Fish wasn’t the only thing on the menu for our Snohomish ancestors, for they also hunted deer and elk. Many Salish hunters were experts at mimicking the sounds of deer and their fawn. They’d set snares and then make a call like that of a fawn or a doe and wait until a deer ran into the snare.

pədxʷit̕xʷit̕il −The time of falling leaves (October)

During this time, of course, the leaves were being shaken from the trees and falling to the ground. The silver salmon runs had ended, and it would be a while before the next salmon would start to run. During this time, vegetation was dying and a different game was sought out to hunt.

The Snohomish people were very proficient duck hunters. Ducks were a very sacred animal in that their spirit power was one of wealth but also, their feathers were collected for regalia, and they were hunted in between salmon runs.

pədƛ̕xʷayʔ − The time of the dog salmon (November)

Dog salmon, or chum, would start its run in November. This salmon was highly prized amongst the Snohomish people. The way this type of salmon was harvested was different than how the silver salmon was harvested. Silver salmon were biting fish, which meant they would bite at a bait line. Dog salmon were not biting fish, so another method was used. Long ago, the dog salmon runs used to be quite plentiful. Instead of using a bait line, our ancestors used a harpoon or a long spear. Dog salmon was dried and stored in baskets, similar to the ones that stored berries. The Snohomish people were very good at making sure they had enough dog salmon for the entire family or village so that no one went hungry.

Other game harvested during this month were bears. At this point in the season, bears were fattening up for hibernation and it wasn’t uncommon for our ancestors to encounter them.

Bears weren’t typically sought out for food. During the winter, it was said that bear meat didn’t taste very good because of all the salmon they’d been eating. However, in the summer bear meat was preferred because the bears had been eating berries and that sweetened their meat.

pədšic̓əlwaʔs– The time to sheath the paddles (December)

During this time, the Snohomish people were settled in their winter villages, and they weren’t traveling so the paddles were put away and sheathed until the weather warmed up. Hunting and fishing were still being done, but mostly the Snohomish people relied on their food stores to get them through the colder seasons.

Typically, the Snohomish people didn’t like being clothed but, in the winter, it was a necessity. They made moccasins, shirts and pants out of buckskin. Some of these items were painted on or beaded. Back then, the beads were either made of shells, pearls, or bones. Men and women alike would wear fur caps made of bearskin to keep their heads warm. Bearskin was also used to make coats or capes.

During the winter, the Snohomish people would paint their faces bright red or a dark red, depending on the material they used. This paint would be put on every morning and taken off every night. The Snohomish liked using this not only because of the vivid color it gave off but because it kept their skin smooth and free from chapping from the cold.