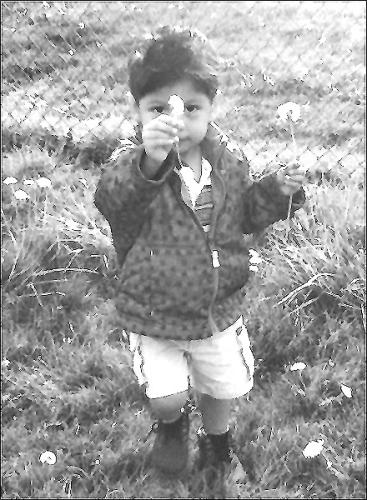

On March 26, 2000, Shaylee Adelle Chuckulnaskit’s birth, a day God gave us our Shay Shay. Shaylee left to the be with the Lord on Friday, October 31, 2014.

Shaylee was very outgoing, confident, silly, persistant, fearless, and she mirrored God’s forgiving ways. She was also a fighter with spirit and had faith that could move mountains. Shaylee loved her sports, she played AAU Marysville Select for a few years and for Totem MS this last year. Shay also played volleyball for Totem MS. Shay had so much of God’s perfect love to give, she especially loved her friends, but her love was mostly to all of her family.

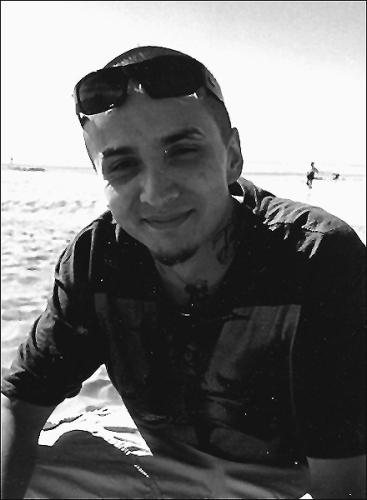

Shay leaves behind, whom she loved and adored most, her dad, Kurt Chuckulnaskit, her mom, Lavina Phillips; siblings, her best friend/sister, Shania, her brothers, Kurtis “Chaska” and Keenan, and her baby/little brother, Kaleb James. Shay also leaves her uncles, Kris Chuckulnaskit, Justin Chuckulnaskit, Percy Phillips III, and Jerry John Phillips; her aunts, Tory Chuckulnaskit, Rhonda St. Pierre, Grace Thornton, Lakota and Jenny Phillips. Shay also leaves her grandparents who she loved so much, Percy and Sandra Phillps, and Larry Thornton. Also leaves all her cousins, Vashti and Veniece, Cheryl and Kristy, Tanessa, Lanay, and Jason, Terrance and Nosh, Quentin and Kordelle, Kelsie and Jessie, Mekiah and Marisa, Jalen, Joey, Preston, Blake, Elwa, and LaVea.

Shaylee had such a radiant personality, crazy humor, and one heck of a beautiful smile! She will be remembered by all her selfies in each of our phones! Shay will be tremendously missed by her family and friends! We will always be CRAY CRAY for our Shay Shay!

We also would like to thank all for their support, donations, prayers, etc. from family to the whole nation for all you have done for our family and Shay, she meant the world to us! God has great things in store for each of you!

Shaylee was preceded in death by her loving grandmother, Cheryl Chuckulnaskit; aunt, Sharmon Phillips, uncle Jason Chuckulnaskit; cousins, Caden and Koby Phillips.

Visitation Thursday, November 6, 2014 at 2:00 PM at Schaefer-Shipman with an Interfaith service to follow at 6:00 pm at the Tulalip Gym. Service will be held Friday at 10:00 am at the Tulalip Gym with burial to follow at Mission Beach Cemetery. Arrangements entrusted to Schaefer-Shipman.