By RICHARD MAUER

rmauer@adn.comApril 20, 2014

UPDATE: The Senate passed the language bill at 3:15 a.m. Monday. The vote was 18-2, with Sens. John Coghill and Pete Kelly, both Fairbanks Republicans, the only no votes. Among the Senators to give impassioned speeches in favor of the bill was Sen. Lesil McGuire, R-Anchorage, who said there wasn’t anything the state could do about what happened to Native language speakers in the past, but it could help people into the future.

ORIGINAL STORY:

JUNEAU — Fearing their language bill was getting caught up in end-of-session politics, Alaska Natives held a demonstration in front of Sen. Lesil McGuire’s Capitol office Sunday, demanding she send it to the Senate floor before it was too late.

After 30 minutes of drumming, dancing, speeches and story telling, McGuire’s chief aide, Brett Huber, said McGuire would do just that, put it on Sunday’s Senate calendar. He said she supported the measure.

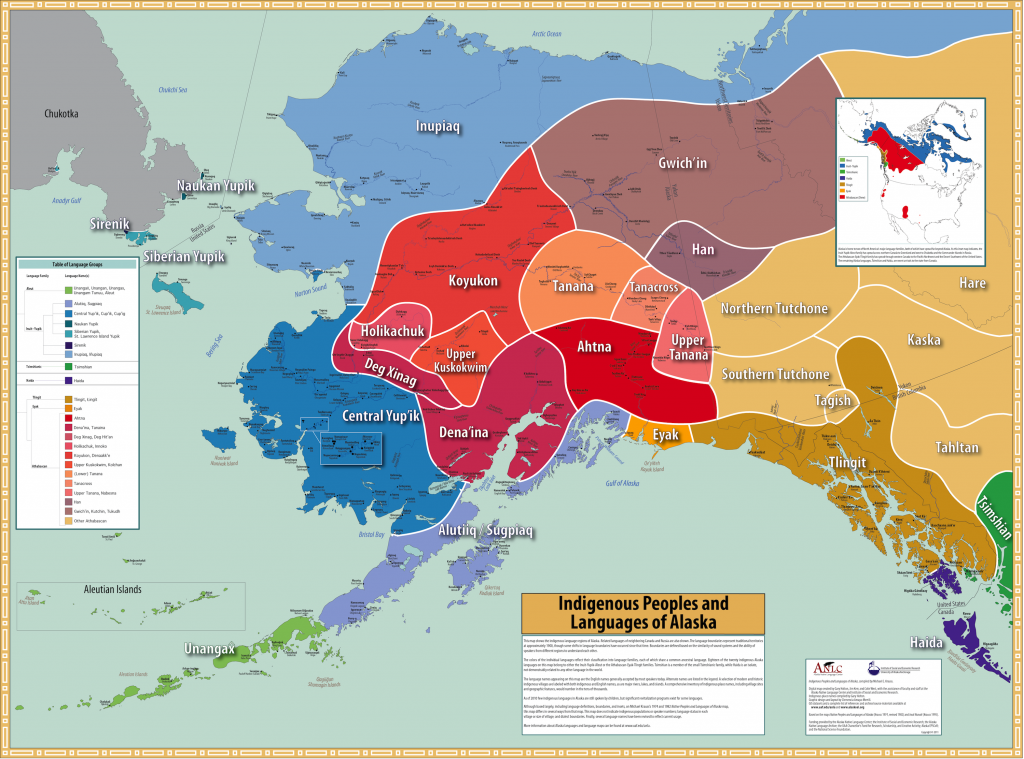

The bill, House Bill 216, had broad backing in the House, where it passed 38-0 on April 16. It would recognize 20 Native languages as official languages of the state, though it would require only that English, the state’s first legal language, be used in official documents and meetings.

Though of little practical effect, Native speakers said the measure was rich with symbolic significance, a recognition that historical efforts by the dominant culture to forbid them their languages was wrong — and had failed. Many in the hallway Sunday had been in the gallery last week as the bill passed the House, cheering after the roll was taken and the tally was unanimous.

The demonstrators, from little children in Easter clothes to elders who needed help to walk, began arriving around noon. The legislative calendar showed that the language measure was parked in the Rules Committee Saturday, a limbo zone for legislation, especially in the waning days of a session. Bills can leap out of Rules and land on the floor, or die there when the session ends — which explains why the word “powerful” often precedes the title, “Rules chairman.”

It’s unclear why McGuire was holding the bill, or even if she was. She was in and out of meetings all day and unavailable for comment. As the demonstration was gathering steam, she walked out of the her office in a bright yellow dress and strolled past the crowd without turning or saying a word. Later, she texted that the majority leader, Sen. John Coghill, R-Fairbanks, had a concern about the bill.

“I am putting it up though, no matter what,” she texted. “Always was going to.”

Coghill later said he didn’t have time to talk, but at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing last week, Coghill said he was concerned that the bill would supersede the 1998 voter initiative that made English the state’s official language and which won by a landslide. He suggested that the bill be changed to declare the Native languages only “ceremonial” and not “official,” but the original bill was left intact.

Before Huber’s announcement, the group was clearly anxious about what would happen.

“It’s real disappointing after what happened on the House side,” said Beth Geiger. “With all the momentum it had, it’s shocking it’s sitting like that.”

X’unei Lance Twitchell, a Native language professor at the University of Alaska Southeast, said he had heard many expressions of support by legislators and was puzzled by the bill’s apparent lack of traction.

“If they support this bill, why don’t they use their political power?” he said.

Later, after Huber announced McGuire would push the bill forward, Twitchell said he was happier but still wanted to see it through. The demonstrators had no plans to leave the hallway, he said.

“We’re going to stay till it passes,” Twitchell said. “If they want us to enjoy our Easter, they’ll put it on the floor first.”

Reach Richard Mauer at rmauer@adn.com or (907) 500-7388.

autonomy, the commission wasn’t seeking reservation status for Alaska’s 229 federally recognized tribes, only one of which is on a reservation — Metlakatla.

autonomy, the commission wasn’t seeking reservation status for Alaska’s 229 federally recognized tribes, only one of which is on a reservation — Metlakatla.