Suzette Brewer, Indian Country Today Media Network

Editor’s Note: The Baby Veronica Case, recently argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, is one of the most important Indian legal battles of the last generation. It is the story of Dusten Brown, a member of the Cherokee Nation, who has invoked the Indian Child Welfare Act to prevent Christina Maldonado, the non-Indian mother of his baby daughter, Veronica, from putting their child up for adoption by Matt and Melanie Capobianco of South Carolina.

That bare outline does not begin to describe the convoluted dimensions of the case formally known as Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. Its drama includes an unplanned pregnancy, a broken engagement, charges of bad faith, an adoption agency that did not comply with federal Indian law, a couple who fought to adopt a child who was never legally eligible, and even the intervention of the Cherokee Nation.

For more background, read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Auld Lang Syne

Chrissi Nimmo had taken a few days off. It was New Year’s Eve 2011, and she and her husband were on a camping trip at Cedar Lake in the Quachita National Forest in southeastern Oklahoma. They had been horseback riding that day and were ringing in the New Year around the campfire with his family when her cell phone started ringing.

Nimmo, assistant attorney general for the Cherokee Nation, thought it was strange that she was able to receive calls in a place that is notoriously void of cell service. She didn’t recognize the phone number, but she answered anyway, thinking it may be important. In fact, it was life-changing.

It was a reporter from South Carolina. The very public transfer of custody involving Baby Veronica to her father was happening that very moment in downtown Charleston—did Ms. Nimmo wish to comment on behalf of the Cherokee Nation?

“Of course I wasn’t going to comment,” says Nimmo. “We don’t comment on confidential juvenile matters, which is what this should have been. But the other side was already out there on television with names, facts and identifying information that was clearly under seal by Judge Garfinkel. But there they were, the Capobiancos, their attorney and the guardian ad litem, all parading this child around the streets of Charleston in front of the cameras. It was, to say the very least, unethical and appalling.”

Nimmo hung up and immediately called the tribe’s then-attorney general, Diane Hammons, to give her boss the heads up in the event that any reporters tried to contact the tribe. Based on the Capobianco’s denied attempt at a stay of transfer until they could file another appeal, Nimmo knew that it was just a matter of time before the case would be back in appellate court.

“We knew when the hand-off happened that they were going to appeal [to the South Carolina Supreme Court],” says Nimmo. “So from that point on, we were focused on two things: Upholding the Indian Child Welfare Act and preparing for the South Carolina Supreme Court.”

Two days later, Nimmo went back to work with no time to waste. For the next four months, Nimmo put in 18-hour days gathering records, going through case files, reading case law, reviewing potential arguments, and collaborating with the appellate attorneys for Brown in South Carolina. She also worked around the clock coordinating the legal and media strategy with national Indian organizations, states’ attorneys general and a growing number of Indian tribes, all of whom had been cautiously watching the case, but were now on red alert for the upcoming legal showdown.

One of those observers was Terry Cross, executive director of the Portland, Oregon-based National Indian Child Welfare Association, who monitored the ongoing dispute with growing unease.

“We try to watch cases where we know it may become contentious and we try to help, but this case just spun out of control,” says Cross. “Look, every adoptive family knows that anything could go wrong at any time in the adoptive process and that it could fall through. But after losing in the lower courts, the first thing this family did was hire a PR firm and start talking to the media about things they know they were not supposed to talk about. That does not portend a happy ending.”

Back in South Carolina, John Nichols, a Columbia-based appellate attorney, had been already been working with Shannon Jones on legal strategy for Adoptive Couple for several months. As of January 2012, however, he was now taking the lead on the subsequent state supreme court hearing.

“This case has taken a track like no other case I’ve ever seen in all my years as an attorney,” says Nichols. “This was expedited before the Supreme Court of South Carolina in just four months, which is record time under any circumstance, but especially for one of this nature.”

Operating under new administrative rules established by the South Carolina Supreme Court in cases where parental rights are being terminated, both sides were required to submit all briefs and responses within a mandatory 30-day filing period, with no extensions granted. The court set April 17, 2012 for the hearing.

In the meantime, growing increasingly frustrated by the Capobianco’s continued media presence, Nichols filed a motion to put a stop to their activities. On their behalf, Trio Solutions, had launched an ugly media campaign designed, said Nichols, to eviscerate his client and undermine the rights of all Indian parents under ICWA. In addition to violating the law and codes of ethics, he says, they displayed a stunning lack of regard for the child at the center of the case by denigrating her father in front of the world. Though the court stopped short of issuing a gag order, the justices did issue a warning: Juvenile cases are sealed under South Carolina state statute and are not open to public discourse.

“The Capobiancos, their lawyers and their PR team broke the law,” says Nichols matter-of-factly. “There is no question that the statute is very clear on these matters. But I at least wanted to send a message that we were not going to tolerate them violating the law on a sealed juvenile case that should have been kept confidential.”

Nichols said that the court’s admonition did seem to slow the firehose of media stories—for a short time. But what did not stop was the marketing and selling of the Capobianco’s side of the story, using Veronica’s name and likeness on a variety of social media to seek attention, support and financial donations to pay their legal fees in their fight to terminate Dusten Brown’s parental rights and retain custody of Veronica.

“Save Veronica” became the clarion call of the Capobiancos’ media strategy. Starting with a website and a Facebook page, they posted regular, emotionally-charged status updates and pleas for money via a “donation” link. Additionally, bracelets, perfume, magnets, artwork and various other trinkets were sold to finance their PR firm and legal defense fund—all the while ginning up public outrage bordering on frenzy toward not only Dusten Brown, but the entire foundation of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Meanwhile, Dusten Brown kept quiet and stayed focused on building his life after returning from Iraq. But he did not like the way the Capobianco’s portrayed him in the media, especially after he allowed them to maintain contact with Veronica after the transfer. In particular, as a parent, it was the unauthorized use of his daughter’s name and likeness to build their case against her own father that hurt the most.

“They plastered her name and face all over the Internet asking for handouts,” says Brown evenly. “I never once asked for a penny from anyone, I never said a bad word about them or the birth mother. But I’ve told my lawyers that I want all those websites and Facebook pages shut down. I do not want them using her that way. If they really love her like they say they do, they wouldn’t do that to her.”

From the beginning, the insidious undertones of class and race in their messaging was clear: The Capobiancos are a well-to-do couple who can afford expensive vacations and private schools for Veronica; Dusten Brown is in the Army. The Capobiancos are both highly educated—Melanie Capobianco, in fact, holds a Ph.D in child developmental psychology (more on that later); Dusten Brown went to Vo-tech. The Capobiancos are white; but Dusten Brown, they argued fiercely—is not “Indian enough” for federal law to apply to them in disrupting their adoption plans.

Therein lies the central question hovering over this case. The legal concept of who is an “Indian” and what constitutes tribal membership has plagued and confounded many in Indian Affairs for centuries. But, regardless of countless attempts to reinterpret, circumvent and override tribal sovereignty regarding their membership, the law is unmistakably clear on the matter, according to Richard Guest, staff attorney and director of the Tribal Supreme Court Project for the Native American Rights Fund.

“As a matter of law, tribes determine their own membership,” says Guest. “Membership is based on a number of factors. Some tribes go by the Census, some go by blood quantum, but some, like the Cherokee Nation, base theirs on the Dawes Rolls—and they are within their rights to do so. Many tribes are now confronted with these issues and are changing their requirements to reflect these complexities, because some people may belong to one tribe, but may be full-blood from several different tribes through their grandparents. One person may appear white or black, but have been raised in the community, speaking the language. Others may be from urban areas and have never seen their homeland, but they’re still tribal members. There are also many marriages between people from different tribes, but their children can only be enrolled in one tribe. It’s a very complex process, especially for the courts.”

One thing is clear, says Guest. Though at first glance Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl is a failed adoption, it carries with it a powerful subterranean threat to the very existence of tribal life in America.

“The Cherokee Nation is a federally-recognized tribe and Dusten Brown is an enrolled member of that tribe. And in the case of Baby Veronica, the terms of the Indian Child Welfare Act are absolutely clear: She is eligible, therefore ICWA applies. To determine otherwise could have far-reaching implications for all Indian matters. The real issue is: Who gets to say who’s an Indian?”

On April 17, 2012, Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl was argued before the South Carolina Supreme Court. By this time, the case has long since blown any semblance of confidentiality and had become high conflict because of the steady diet of media assaults on Dusten Brown, ICWA and Indian tribes in general.

Because of potential security issues, the Court took the unusual step of closing the courthouse to the general public. Only the parties, their attorneys and essential personnel were allowed into the hearing. Both sides were taken into and out of separate entrances and elevators by police escort and were not allowed even to pass each other in the hallways. Relations between the two families had soured to the point where they had to be sequestered in separate chambers before the arguments.

Outside the courthouse, protesters for the Capobiancos had gathered and were going full force with signs and banners beseeching the South Carolina Supreme Court to “Save Veronica.” Several media outlets also covered the hearing, which had by then become national news.

Inside the courthouse, the atmosphere was tense and unyielding as the attorney for the Capobiancos, Robert Hill, argued that Brown was a deadbeat dad who did nothing to contribute to the birth mother or his child during her pregnancy. Under state law, he said, Brown therefore had not established or obtained parental rights. Because he had not established paternity or obtained parental rights, ICWA did not apply under the definitions of the act. Additionally, Hill argued that because Veronica had already been with her adoptive family, removing her from the Capobiancos would psychologically harm her. The court should find “good cause,” he said, to deviate from the Indian adoptive placement preferences outlined in ICWA and return her to the Capobiancos.

John Nichols, appellate attorney for Dusten Brown, defended his client by asserting that all along, the mother and the Capobiancos had conspired and colluded to hide this adoption and obfuscate his Indian heritage, knowing full well that he would object. Nichols pointed out that they had waited until Brown was in lock down at Ft. Sill to serve him the notice of parental termination. Brown’s immediate reaction upon hearing that his child had been adopted without his consent or approval, he said, was to seek custody. But most importantly, Nichols argued that Dusten Brown, as a tribal member, is considered a “parent” under ICWA and that Veronica is therefore by definition is “an Indian child.” These facts alone, he argued, required that the Court rule in favor of Brown.

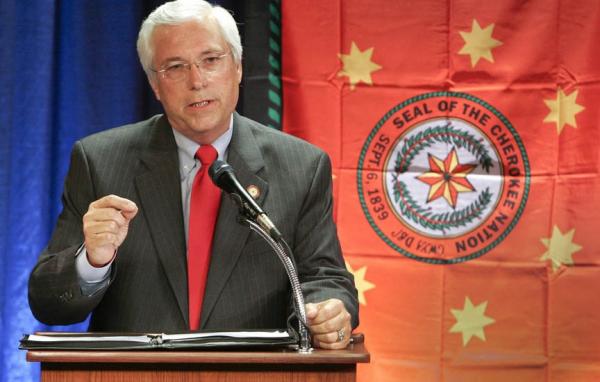

Chrissi Nimmo, arguing on behalf of the Cherokee Nation, also told the court that they should only consider the time that Veronica was with the pre-adoptive parents from birth to four months, because it was only then that Brown learned of her situation and sought custody. Further, Nimmo asserted that gaining temporary custody of a child in violation of the law and maintaining custody throughout protracted litigation does not entitle the adoptive couple to permanent custody.

Three months later, on July 26, 2012, the South Carolina Supreme Court issued a 78-page ruling affirming the lower court rulings of Judges Garfinkel and Malphrus. In a 3-2 decision affirming Brown’s status as an Indian parent, Veronica’s status as an Indian child, the court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act. In a stunning rebuke of the birth mother and the Capobiancos, the court wrote the following:

“Mother testified that she knew “from the beginning” that Father was a registered member of the Cherokee Nation, and that she deemed this information “important” throughout the adoption process.5 Further, she testified she knew that if the Cherokee Nation were alerted to Baby Girl’s status as an Indian child, “some things were going to come into effect, but [she] wasn’t for [sic] sure what.” Mother reported Father’s Indian heritage on the Nightlight Agency’s adoption form and testified she made Father’s Indian heritage known to Appellants and every agency involved in the adoption. However, it appears that there were some efforts to conceal his Indian status. In fact, the pre-placement form reflects Mother’s reluctance to share this information:

the birth mother did not wish to identify the father, said she

wanted to keep things low-key as possible for the [Appellants],

because he’s registered in the Cherokee tribe. It was determined that

naming him would be detrimental to the adoption.”

For the first time in several years, Dusten Brown and his legal team breathed a sigh of relief. It was felt that the case had finally reached its conclusion and he and his new wife, Robin, and Veronica, could move on with their lives in Oklahoma.

But it was not to be. On October 1, 2012, the Capobiancos, who now has the estimable Lisa Blatt of the Washington, D.C. firm of Arnold and Porter, as their lead counsel, filed a petition of certiorari with the United States Supreme Court. Three months later, on January 4, 2013, certiorari was granted in Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. The most important Indian law case in three decades was going before the nation’s highest court.

Read more at https://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/06/12/fight-veronica-part-4-149873