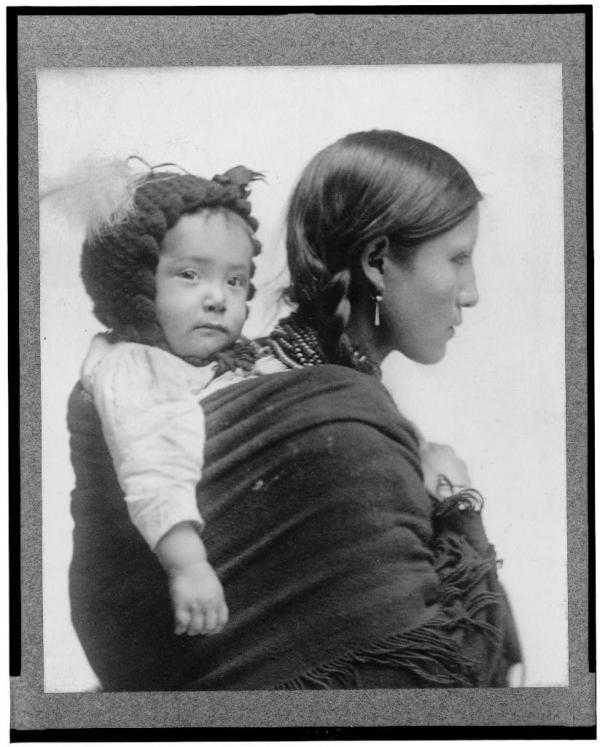

This image shows a Native woman from the Plains region carrying a baby on her back.

Until the advent of genetic genealogy, knowing your ancestry meant combing through old records, decoding the meaning of family heirlooms and listening to your parents and grandparents tell you about the “good old days.” For anthropologists and archaeologists interested in going back even further in time, the only reliable means of understanding human history were trying to interpret ruins or remnants of skeletons or other information uncovered at the site of remains.

DNA testing has changed all that, allowing us to delve far deeper into our past than before and with a much higher degree of accuracy. Although there are many issues stirred by DNA testing, none is more provocative than interpreting our family and tribal ancestries.

Nowhere is this more apparent than among the Native American tribes in the United States. I recently wroteabout a large-scale genetic analysis among the American population by personal genetics and genealogy company 23andMe, using its extensive database to begin to decipher the ancestral origins of various ethnic groups in the United States.

Though the study involved more than 160,000 people, less than less than one percent of those who participated self-identified as Native American. Rose Eveleth, a journalist writing for The Atlanticsuggests that this lack of participation may have a lot to do with how Native tribes perceive genetic testing:

But when it comes to Native Americans, the question of genetic testing, and particularly genetic testing to determine ancestral origins, is controversial. […] Researchers and ethicists are still figuring how to balance scientific goals with the need to respect individual and cultural privacy. And for Native Americans, the question of how to do that, like nearly everything, is bound up in a long history of racism and colonialism.

[…] for Native Americans, who have witnessed their artifacts, remains, and land taken away, shared, and discussed among academics for centuries, concerns about genetic appropriation carry ominous reminders about the past.

Eveleth references the widely publicized case where the Havasupai Tribe living near the Grand Canyon sued an Arizona State University scientist for using genetic samples collected from the tribe to conduct research outside of the purpose of the original study. The crux of the issue was the consent form, which covered a broad range of uses for the samples—a fact that the tribes claimed was not explained to them appropriately.

Although the tribe won the case, reclaimed the samples and settled with the university for $700,000, the issue captured the front pageof the New York Timesand put “every tribe in the US on notice regarding genetics research” as Native American tribal research ethics expert Ron Whitener quotedin an article titled “After Havasupai Litigation, Native Americans Wary of Genetic Research” published in the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A.

Around the same time that the genetics of the Havasupai were being studied, another high profile issue bought Native American tribes in conflict with researchers. The Kennewick Man, an approximately 9,000-year-old skeleton was discovered by accident in 1994 in Kennewick, Washington. The Umatilla Tribe, who were indigenous to the region, sought to reclaim the remains under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to bury it in accordance with traditions. Anthropology researchers who wanted to study the skeleton however, argued there wasn’t enough evidence to convincingly show that the remains were Native American and therefore should not be returned. This resulted in a widely publicized eight-year-long legal dispute between scientists and the government that ended in 2004 with the court ruling in favor of the archaeologists, a decision that the tribes were expectedly unhappy with.

Now, the issue has come under the spotlight once again with the Seattle Times reportinglast month that preliminary DNA analyses indicated that the Kennewick Man was indeed of Native American ancestry.

RELATED: The Long Legal and Moral Battle Over Kennewick Man

This piece originally appeared on February 2 at the Genetic Literacy Project. Read the rest of the article here.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/02/03/why-native-americans-are-concerned-about-potential-exploitation-their-dna-158993