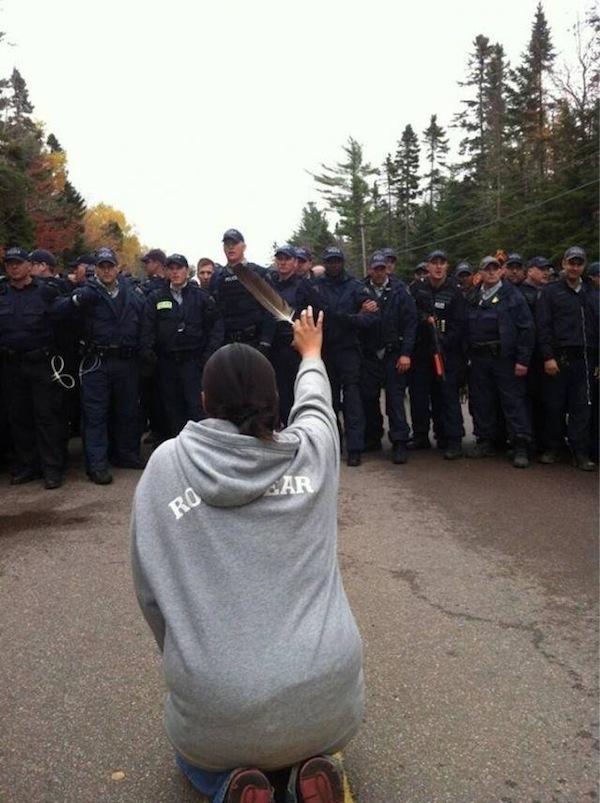

This photo of 28-year-old Amanda Polchies kneeling before Royal Canadian Mounted Police while brandishing an eagle feather during anti-fracking protests in New Brunswick has become iconic as a symbol of resistance to destructive industrial development—and of women’s role in fighting for the water.

By Martha Troian, Indian Country Today Media Network

As Amanda Polchies knelt down in the middle of the blocked-off highway with nothing but an eagle feather held aloft separating her from a solid wall of blue advancing police officers, she prayed.

“I prayed for the women that were in pain, I prayed for my people, I prayed for the RCMP officers,” the 28-year-old Elsipogtog First Nation member told Indian Country Today Media Network. “I prayed that everything would just end and nobody would get hurt.”

As Polchies faced off against hundreds of RCMP officers on the highway near her community, she couldn’t help but notice how many of those beside her were indigenous women—the keepers of the water, fighting to keep fracking chemicals out of the ground.

“So many people got hurt,” she said as she recalled “looking around, seeing all of these women.”

Polchies was just one of the dozens of indigenous people who grappled with fully armed RCMP officers just south of a town called Rexton on October 17, 2013. Very early that morning, the RCMP had moved in on an encampment of Mi’kmaq Warrior Society members and others as they slept. They were enforcing an injunction against the blockade of a worksite for SWN Resources Canada, the company that has been searching for shale gas in the area since spring.

RELATED: Police in Riot Gear Tear-Gas and Shoot Mi’kmaq Protesting Gas Exploration in New Brunswick

Photos and video of the raid show several snipers wearing camouflage or dressed all in black lying in surrounding fields. Hundreds of photos have emerged on social media from this day that show Indigenous people—both men and women of all ages—confronting police. But it’s hard not to notice how many of those images show indigenous women. Many women can be seen drumming, singing, praying and even smudging RCMP officers with the cleansing smoke of sage, cedar, sweetgrass or other traditional medicine.

RELATED: 10 Must-Share Images, Scenes and Far-Flung Shows of Support in the Mi’kmaq Anti-Fracking Protest

By the time Polchies arrived that afternoon, the situation had become a standoff. On one side, RCMP officers in a straight line across the highway. On the other, opponents to shale gas—the majority of them Mi’kmaq. Before long, the situation became a fight. Arguments erupted, women screamed, and weaponry was raised. The RCMP used tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and even dogs. Polchies saw two women hit with pepper spray in the face. Seeing these women in pain “spoke to” her, she said.

“I just realized I had a feather in my hand,” Polchies said. “I just knelt down in the middle of the road and I started praying.”

Polchies didn’t realize it at the time but a reporter with the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network snapped a photo from behind with his phone and posted it to Twitter. That image of Polchies kneeling down with a raised eagle feather, facing a line of officers in front of her, has come to symbolize the conflict between First Nations and the government-supported oil and gas companies that covet the resources under their land. And central to that conflict are women, the defenders of the water.

Related: From Beginning to End: Walking the Mississippi River to Celebrate and Cherish Water

SWN Resources Canada, a subsidiary of Texas-based Southwestern Energy Company, has a license to explore 1 million hectares in the province of New Brunswick. While the company has only been searching for shale gas deposits, protesters believe that once they find them, it won’t be be long before the company employs the controversial technique known as fracking to get at it. Many fear that the practice, which involves injecting toxic chemicals into cracks in the rock to loosen the deposits, will contaminate and destroy local water systems. Protesters want to see SWN pack up and go home. Many women have been arrested, jailed and even injured as they passionately defend their life-giving water supply. Protests have been ongoing since June.

RELATED: Fracking Troubles Atlantic First Nations After Two Dozen Protesters Arrested

Indigenous women are traditionally responsible for water, said Cheryl Maloney, who is from Shubenacadie First Nation, a Mi’kmaq community near Truro, Nova Scotia, and is president of the Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association.

“Women have a connection to the water based on the moon and our cycles,” Maloney told Indian Country Today Media Network. “But that alone doesn’t explain the intense connection that our young people, the seventh generation have.”

There is an awakening going on, she said, with young women revitalizing their culture after years of seeing it being oppressed and taken away from their families through residential school.

“All the prophecies are pointing to these young people,” she said. “Our young people are spiritually awakened. Make no mistake, they are spiritually driven and following their ancestors.”

Haley Bernard, 22, of Pictou Landing, Nova Scotia, heeded the call. The recent graduate of Cape Breton University in Mi’kmaq Studies gave her support on the front lines on October 17, answering her best friend Suzanne Patles’ cry for help.

“Women are protectors of the water, we have water in our body, we carry a child, and they’re covered in water, so we’re meant to do that. We’re supposed to do that,” said Bernard. “We know the law, we know our treaties, we know what we’re supposed to protect.”

For her part, Polchies never planned on becoming a symbol. When the line of RCMP officers moved forward, she remained on her knees.

“I heard someone behind me saying, ‘Keep praying if you’re not going to get up.’ That’s what I did.”

All she could see was darkness from the uniforms that surrounded her.

“I just closed my eyes and held my feather and prayed for protection,” she said. “Then all of a sudden there was light.”

Polchies said that’s when RCMP officers moved to the other side of the road and started arresting people. One of the women Polchies saw was 66-year-old Doris Copage, a respected Mi’kmaq Elder from the Elsipogtog First Nation.

“I got pepper sprayed, I didn’t know what that was and I didn’t think they would do anything to the women,” Copage told Indian Country Today Media Network.

Armed with only a crucifix, Copage had set out that day with her husband in response to a call for help from the protest site. Seeing the gravity of the situation, Copage started to recite the rosary with the community’s priest, also present.

“The [RCMP officers] were really mocking at us, talking and laughing,” Copage said, adding that she questioned one of them at the frontline.

“I asked him, ‘Are you really ready to kill the Natives?’ ” she said, and was shocked by his answer.

“He looks at me and says, ‘Yes, if I have to,’ ” Copage said. “I said, ‘How many are you planning to kill?’ He didn’t say how many. He put his three fingers out.”

Copage told the officer that the indigenous people had no protection and that she had only came out as an Elder to pray. She intends to continue standing up for her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and the community.

“I want to call it ‘protect,’ ” said Copage, rather than “protest.” “We are here to protect our water, our land. We have a river. It’s a beautiful river, we love it and we respect it.”

Of the 40 people arrested, three men are still in custody, with no trial date in sight. Aaron Francis, Germaine “Junior” Breau and Coady Stevens, members of the Mi’kmaq Warrior Society, pleaded not guilty in New Brunswick Provincial Courthouse on Friday November 8, according to a statement from the society.

“I am happy they have entered their plea of not guilty,” said Susan Levi-Peters, former Chief of Elsipogtog First Nation, in a statement on November 8, “and I am saddened that they are still locked up for protecting our women and elders who were for fighting for our water and land.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/11/10/mikmaq-anti-fracking-protest-brings-women-front-lines-fight-water-152169