By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News; Photos courtesy of Libby Nelson, Tulalip Environmental Policy Analyst

Wilderness. The wild. Whether intentional or not, using the world “wild” to designate landscape and environment sets the land apart from us. Americans are civilized, Natives are savages, and the land is wild. Sound familiar? Because of American formal education and informal borrowing of traits from other cultures, Americans believe they can visit the wild, but can never live in it. Americans are trained to think that those who do choose to live in the wilderness are either Natives (read savages) or half-crazed tree huggers.

But the concept of wilderness was obsolete the minute it was born. We, as a Native society and Tulalip people, know every inch of this land used to be Indian Country. Every inch. There is not now, nor has there ever been, a “wild” or a “wilderness” on this continent. All things are related. This notion of connectedness to all things was so central to our ancestors, to the very essence of Native culture, but has dissipated as generation after generation of Native peoples have found themselves urbanized; slowly transformed by the contemporary world of independence, big cities, and a relentless dependence on technology.

So then how can we reasonably begin to understand our ancestors, their actions, thoughts, and values? If we live in a modern time that is inherently different in nearly every respect than the time of our ancestors, how can we truly grasp the culture we stem from? The culture we fight to hold onto, both externally and internally, every single day, while the world around us constantly tells us to give it up, get with modern times, and stop looking backward, look forward.

There is no simple solution, yet as we look around we can clearly see a persistence and resurgence of Tulalip culture that we refuse to let die. There is the plan for Lushootseed immersion classrooms, the stead-fast work of our Rediscovery Program, the restoration of the Qwuloolt Estuary, and, most recently, the reintroduction of our ancestral mountainous areas to a new wave of Tulalip citizens, known as Mountain Camp 2015.

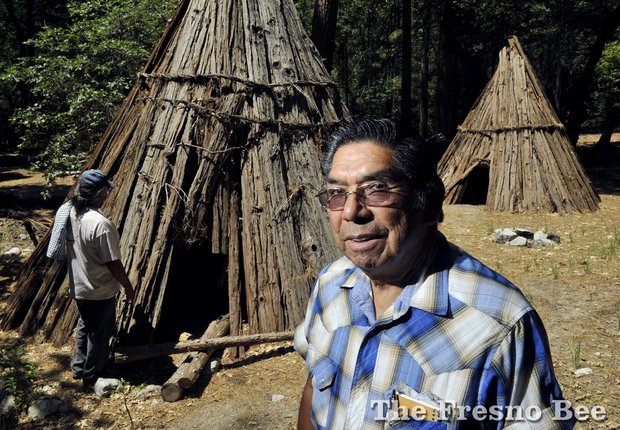

The idea behind Mountain Camp helps us begin to answer the critical questions about how we keep in touch with our ancestors in modern times. Instead of bringing traditional teachings to an untraditional space, we learn our ancestral teachings in an ancestral space, to walk as they walked. The pristine swədaʔx̌ali co-stewardship area, located 5,000 feet up in the Skykomish Watershed, was a space where our ancestors once resided. It was a place where they hunted, gathered, and lived only off the sustenance the land offered them. Most importantly, after all these years, the swədaʔx̌ali remains a land our ancestors would recognize today, unhampered by urban cities and deconstruction.

“I think for our youth to be up in the mountains it is critical for them to get a strong, firm understanding of who they really are as Tulalip people,” says Patti Gobin, Tulalip Foundation Board of Trustee. “It’s been a long time since our people, our children in particular, have been allowed into these areas. After the signing of the treaty, we were confined to the reservation at Tulalip, and many of us grew up thinking that’s all we were, Tulalips from a reservation. But we are far more than that. From white cap to white cap, as Coast Salish people, this was our ancestral land and it means everything to have our children up here to allow the spirits of our ancestors to commune with them and talk to them, and for them to experience what it is to be out in the wilderness, the way we have always lived.

“If they are given the gifts of what the woods have to offer them and they have ears to listen, then those gifts will strengthen them as young men and women. They’ll never forget this experience and they’ll always come back here and they’ll always fight for the right to come back here, which is critical for future generations.”

For the inaugural Mountain Camp 2015 (held in mid-August), three camp leaders led eight Tulalip tribal members, all 7th and 8th graders, in the experience of a lifetime. They spent five days and four nights in the swədaʔx̌ali and surrounding areas living as our ancestors lived; setting up and taking down camp as they moved locations, singing, storytelling, making traditional cedar baskets, foraging, berry picking, preparing meals, building fires, using the crystal clear lake to cleanse their bodies and spirits, learning traditional values in the sacred land, and coming together as a supportive family.

In order to give the Tulalip youth the most impactful experience possible, the Natural Resources Department teamed with Cultural Resources and Youth Services to develop two main themes for the camp: reconnecting to the mountains and x̌əʔaʔxʷaʔšəd (stepping lightly). Both themes aspire to reunite the children with teachings and values central to our ancestors; recognizing the connectedness of all things while respecting the Earth.

“Mountain Camp is all about having a space for kids to come up and just enjoy the outdoors, connect with their mountain culture, learn how to camp, learn how to be out here and be safe,” says camp leader Kelly Finley, Natural Resources Outreach and Education Coordinator. “I grew up in the mountains hunting, fishing, and playing in the trees. It was a vital part of my youth and to this day I love being out there. It is an honor to provide an opportunity for young people to love the outdoors as I do. I hope through this experience there will be a better understanding of our natural world and how we all connect to our environment. I look forward to continue this work next year with new and returning students.”

In keeping with their traditional teachings the youth introduced themselves to the mountains and forest that make up the swədaʔx̌ali region. They took turns stating their names, their parents’ names, and the names of their grandparents. The mountains took notice and later that night swədaʔx̌ali formally introduced itself to the kids in the form of a glorious show of thunder and lightning.

“Thunder is medicine to our people, it was the mountain’s way of welcoming our people back to the place we’ve been absent far too long,” says Inez Bill, Rediscovery Program Coordinator. “The children were in an area where the spirits of our ancestors could see them. We, the elders who volunteered and visited the youth on their camp, did our best to impart the meaning and importance of what they were doing. They were experiencing a place, a spirit of our ancestors that most people will never be able to experience. We hope that experience helps lead those youth to live a good life. As younger people they are in their most formative years. We used to have rites of passage, and for these youth, Mountain Camp represented a rite of passage for them.”

Indeed, the Tulalip elders and volunteers added to the overall experience of the youth; helping to explain how their ancestors were one with their environment and lived a fulfilled and spiritual life, all without the uses of cellphones, computers, T.V., and the internet. A true highlight was the elders teaching the youngsters how to make their very own cedar baskets so that they could go huckleberry picking during their brief stay in the mountains. The messages of finding strength and beauty in all experiences with nature were taken in by the youth and each did his and her best to internalize those values.

“The elders have been telling us stories about what they used to do when they used to go berry picking, and how it was tradition that they make it look like they weren’t even there. They just picked a little bit and moved along,” explains camp participant Jacynta Myles. “They made cedar bark baskets and used them for berry picking baskets. You can go from blackberries to huckleberries and store practically anything in it.

“I love the area. How we woke up to thunder this morning, I’ve never heard it that loud. I think every area in the woods is pretty special, but being here in this area, all together, makes it even more special. And we’re having fun.”

“It’s all about going into the wilderness, no electronics or nothing like that,” says youth participant Sunny Killebrew. “We’re just like on our own, no parents, just depending on ourselves and making new friends. We’ve been learning that this is the land where are ancestors were raised, grew up, and lived. They hunted, they ate, they slept, they did everything on this land right here. It feels good, like I’m doing something they would want me to do.”

For the tribal elders and everyone involved who contributed to making Mountain Camp a reality, it was a dream come true to witness the camp youth as they one-by-one grasped the importance of walking in their ancestor’s footsteps. The entire project had been in the works over the last few years, allowing Natural Resources the necessary time to find funding and the resources to build a Mountain Camp program for our youth.

“This, as the first year, was a big learning experience for all of us. While there are things we might tweak for next year, overall we believe this first year was a big success and deeply worthwhile, as measured by the experience these eight kids received and all that we, as program leaders, learned as it unfolded,” said Libby Nelson, Tulalip Environmental Policy Analyst. “Success this year can be attributed to the collaboration with our Cultural Resources, Language and Youth Services staff; and a very successful and helpful partnership with the YMCA Outdoor Leadership Program in Seattle, the US Forest Service, and our own Rediscovery Program in Tulalip’s Cultural Resources division.

“This Mountain Camp experience presented an opportunity to reconnect tribal youth to these inland, mountain ancestral territories where their ancestors lived, while also explicitly reserving rights to continue using these areas for hunting, fishing and gathering.”

From practically being inside a thunder and lightning storm at an elevation of 5,000 feet, to storytelling in their Lushootseed language as they witnessed a meteor shower, to creating their own cedar bark baskets for huckleberry picking, the Tulalip youth created many memories that will last a lifetime. As they grow and mature into adults, their sense of appreciation for what they were able to be a part of and experience will undoubtedly grow immensely. It’s a difficult task for anyone to be expected to live as their ancestors lived, let alone asking that of a 7th or 8th grade student. In honor of their efforts and achievements while participating in Mountain Camp 2015 the youth were honored with a blanket ceremony when they got back home to Tulalip.

“The ceremony was to acknowledge what the kids went through. It was an accomplishment for them to go through everything that they did while up in the mountains, living in nature,” continues Inez Bill. “They didn’t have their cell phones or any of the other electronic gadgets they would have back home. They experienced something together, they grew together, and they had a rite of passage together. I covered the kids with blankets as a remembrance of what they went through. The ceremony recognized that rite of passage, of how we want them to be as young people.

“In our ancestral way, they were brought out to nature to find their spiritual strength. I think later in their lives, that spiritual strength will give them direction and confidence when they need it most. And for the parents and grandparents who were at the ceremony, I think they were happy and truly touched.”

Following the ceremony the camp participants mingled a while longer, still wrapped in their blankets, and talking about their favorite moments from Mountain Camp. Going to their ancestral lands, being immersed in their cultural teachings, a rite of passage, experiencing nature as it was meant to be experienced. There are so many possible takeaways, but none bigger than that of camp participant Kaiser Moses who says, “I feel empowered. I feel I can do anything!”

Plans are already underway for Mountain Camp 2016. Stay on the lookout for more details and registration information in future syəcəb and online on our Tulalip News Facebook page.