Irish culture is filled with tales of fairies, banshees and leprechauns, and there is nothing as Irish as a good story. It only makes sense then that there could be a good Native American story about the Irish, maybe as unprovable as the others, but as one archaeologist said, “Anything is possible.”

There are records that suggest the Irish came to America before Christopher Columbus, but while there is no solid evidence, there certainly are hints.

One of the first recorded curiosities originated in 1521, when Spaniard Peter Martyr took reports from Columbus and other explorers who had investigated the Southeast coast of today’s South Carolina and Georgia. A baptized Chicora Native and a Spanish explorer reported to Martyr that they had come upon a group of people who called themselves the Duhare.

The Duhare were different than the Chicora Natives in the area. While all of the local Natives were described as having varying degrees of brown skin, the Duhare were described as white-skinned with brown hair that hung to their heels. They were said to herd deer in the way that Europeans herded cattle. Martyr wrote that the fawns were kept in the houses and the deer would go out to pasture during the day, returning at night to suckle their fawns. After the deer had nursed their young, they were milked and the milk was turned to cheese.

Deer milk has been celebrated in Gaelic poetry but usually in mythical situations. Reindeer were herded in Scotland until the 1300s, and a paper by Erin NhaMinerva, from Ireland, mentions deer being milked, but more in mythic terms than as a regular part of the diet.

There was other evidence that these Duhare could have been Irish. They were said to keep poultry, chickens, ducks, geese and other similar fowl, and potatoes were said to have been grown in the area, though they were not yet an important food in Ireland.

While the word Duhare may have a bit of an Irish ring to it, no Irish historian could be found to say it was derived from the old Irish language. And besides the few unusual incidents above, the Duhare lived as the neighboring Natives did.

In West Virginia, there was a ruckus when Dr. Barry Fell, a professor emeritus at Harvard University, said he found writing on a rock he described as “Christian messages in old Irish script.” Although he was the editor and co-author of eight books that deciphered ancient writings, Fell found himself discredited by other experts when it came to this particular rock writing. In a blog called Bad Archeology, Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews says Fell’s arguments were not convincing. Fitzpatrick-Matthews wrote, “His [Fell’s] analysis of supposedly Celtic elements in Native American placenames and languages is fanciful; his identification of scratches on rock surfaces as Irish Ogham script shows his lack of familiarity with real Ogham.”

Nicholas Freidin, doctor of philosophy and anthropology professor at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia said: “The whole thing is simply rubbish, part of the ‘lunatic fringe’. There is no evidence whatsoever of any European presence in West Virginia before the 17th century. To perpetuate this nonsense would be a disservice to both Native peoples and professional archaeologists.”

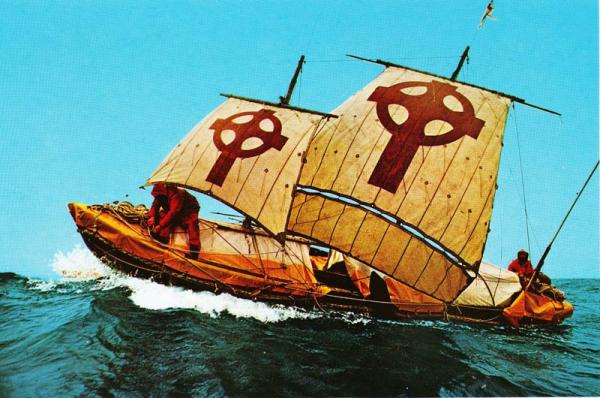

And yet, in the 1500s, the Vikings described the Irish as able seamen who traveled extensively and great distances, as far as Iceland in the 10th century. In 2000, adventurer Tim Severin published a book called The Brendan Voyage about a journey he made in a leather-bound boat built to sixth-century Irish standards. His goal was to see if he could follow the path of an Irish monk who is said to have sailed from Ireland to Greenland and then Newfoundland.

According to the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia, Saint Brendan, the Irish monk who sailed to a wooded paradise, lush with fruits. He had endured a “pelting with rock from an island of fire, seeing a pillar of crystal and encountering a moving island before finally coming upon the Promised Land, which came to be referred to as the Fortunate Islands.

Brendan explored the area for seven years before returning to Ireland, his boats filled with gems. No one is exactly certain where the Fortunate Islands were, although Columbus mentioned them in Martyr’s book.

The New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia and other sources speak of the Irish being the first white men to come to the Americas before Columbus, perhaps as many as 1,000 years before. The glory of that adventure is given to “MacCarthy, Rafn, Beamish, O’Hanlon, Beauvois, and Gafarel,” in a book called Saints In The Limelight by Siglind Bruin.

Those accounts match the Vikings’ claims that the Irish occupied an area south of the Chesapeake Bay called Hvitramamaland (Land of the White Men) or Irland ed mikla (Greater Ireland), notes the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia.

The New Advent says the Shawano Indians recognized a white tribe in Florida, said to have had iron implements. “In regard to Brendan himself the point is made that he could only have gained a knowledge of foreign animals and plants, such as are described in the legend, by visiting the western continent,” New Advent writes.

Interestingly, Martyr’s book refers to islands within Columbus’s route along the North American coast as the Fortunate Islands.

“All things are possible,” Kent Reilly, professor of archaeology at Texas State University and field anthropologist consultant for the Muscogee Nation of Florida, said. “There were many Europeans here; there were the Welsh in 1288, and the Vikings. But there is no archaeological evidence, no ceramics or metal, and as far as I know, there are no stories among the Southeast peoples about white-skinned, blue-eyed people in that area. There is no archaeological evidence, as far as I know.”

According to a website called, “Hidden Ireland: A Guide to Irish Fairies,” Saint Patrick brought Christianity to Ireland but, “from among the ancient tribes and kingdoms of ancient Ireland, whose religions worshipped the trees and lakes, stones and animals of the wild landscape. Such gods and beliefs would not die easily.”

Would it be so hard to imagine if the Irish left their increasingly Christian homelands in search of a place they could follow their ancestral traditions? In any case, it makes a nice story, and as History.com notes, “Spinning exciting tales to remember history has always been a part of the Irish way of life.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/03/17/were-irish-living-southeast-columbus-arrived-154030?page=0%2C3