Killer whales hunt gray whale calves as they migrate across a canyon in Monterey Bay.

May 6, 2013

By PETER FIMRITE — San Francisco Chronicle

SAN FRANCISCO — Scores of killer whales are patrolling Monterey Bay, ambushing gray whales and picking off their young as the leviathans attempt to cross a deep water canyon that bisects their annual migration route.

It is a desperate situation for the migrating mother whales, which are trying to lead their calves through a gauntlet of hungry orcas to reach their feeding grounds in Alaska. Whale watchers and scientists, who are crowding onto boats to witness the action, have described it as the “Serengeti of the Sea.”

“It’s pretty scary and sad to watch, but this is nature,” said Nancy Black , a marine biologist and co-owner of Monterey Bay Whale Watch . “It’s a big battle, with the mother trying to protect her calf, and there is a lot of commotion and splashing in the water.”

Scientists say the violent drama, involving fleeing whales and pursuing packs of orcas, is an annual extravaganza of death off the coast of Monterey that is growing in intensity as the number of whales and orcas increase.

The mother gray whales and their calves leave their breeding grounds in Baja, Mexico, in April and travel north along the Northern California coast this time each year. As many as 35 whales and calves a day are swimming by right now, hugging the shore trying to elude predators, Black said.

The problem for the mothers and calves is that they must navigate around a deepwater depression, called the Monterey Submarine Canyon, at Point Pinos.

Transient killer whales, which at 22- to 26-feet-long are the ocean’s apex predators, congregate along the edges of the canyon, which starts a quarter mile from shore and is 6,000 feet deep in the middle. They wait for the big beasts — which are about 45-feet long — to attempt the crossing, kind of like crocodiles waiting for migrating wildebeests to swim across the Nile.

The more stealthy grays take the long way around, sticking close to shore and swimming through the kelp beds, but some of the more bold or hurried whales cut across the canyon, using sonar to follow the contour lines at the bottom.

“It is one of the few places on the gray whale migration where they have to leave the protection of the shore,” said Black, who has been studying killer whales since 1992 and is considered the Bay Area’s foremost expert. “The killer whales come in the area and patrol the canyon, searching for calves.”Most of the attacks occur along the edge of the drop off, where packs of between four and seven mostly female orcas use the cover of deep water to approach from underneath, said Black and other researchers. It is not an easy kill. The calves are 18- to 20-feet long, weighing many tons.

Working as a team, the “wolves of the sea,” as they are known to some Native American tribes, surround and harass the mother, separating her from her child. While she is occupied, other orcas batter and attempt to drown the calf.

“It’s pretty brutal,” Black said. “The mother will stay there trying to protect her calf and sometimes roll upside down to allow the calf to get up on top of her, but the only way they can save themselves is by moving toward shore. It takes two to three hours, sometimes up to six hours, to kill a gray whale calf.

“It is, say marine biologists, a spectacular example of the natural interplay between two of the largest, most dynamic, creatures in the sea and a sign that the ocean ecosystem is slowly improving on the Pacific coast.

The killer whale, Orcinus orca , is the largest, most intelligent of the world’s ocean predators. They can live up to 100 years — the oldest known orca is believed to be a 96-year-old female — but are highly susceptible to toxins, which accumulate in their tissues.

The animals, which are actually members of the dolphin family, were originally called matadors de ballenas, or “whale killers,” by the Spanish who witnessed them hunting the large cetaceans. The words got reversed when translated into English.

The distinctive black-and-white mammals have an incredibly complex, and remarkably stable, matrilineal social structure in which the sons spend their lives with their mothers, except for occasional dalliances with females outside the family group. Different groups feed on different things and are believed to have different languages and even cultures that are passed down through the generations.

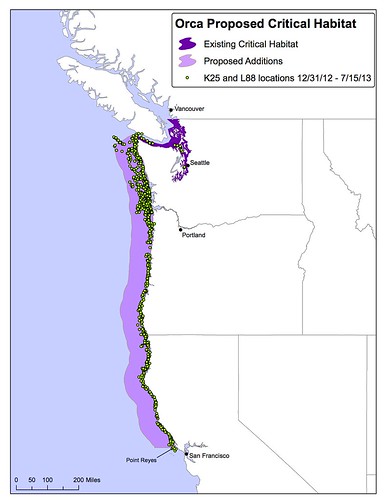

The endangered southern resident orcas of Puget Sound, in Washington, feed on salmon. Offshore orcas eat schooling fish and sharks and the transients that frequent Monterey Bay prey exclusively on marine mammals.

Mammal eating orcas have been known to prey on birds and even terrestrial mammals, such as deer and moose swimming between islands along the northwest coast, but there has never been a documented killing of a human in the wild.

The Monterey orcas have been spotted attacking sea lions, elephant seals, harbor seals, dolphins and porpoises, but gray whale calves are especially coveted. Black said she has seen as many as 25 killer whales feeding on a blubbery carcass, which can take between 12 and 48 hours to consume.

The drama unfolding now along the Monterey coast was unknown to researchers until about 1992, when the once vast gray whale populations began to recover after being driven nearly to extinction by whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The population rebounded from about 4,000 in the 1930s to 26,600 in 1999 , according to estimates by the National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle . The recovery is nevertheless still shaky, according to experts. The number of grays dropped to 17,000 in the early 2000s as a result of the El Niño weather pattern and other factors that affected their food supply. There are now between 19,000 and 21,000 gray whales in the Pacific, according to researchers.

Forty of the approximately 140 killer whales that marine biologists have identified through their markings since 1992 have been spotted this year circling Monterey Bay, which marine biologists consider one of the best places in the world to study the creatures. They have, over time, noticeably learned from their mistakes and honed their hunting skills, Black said.

“The gray whale population has gotten bigger over the last 20 years and the killer whales have gotten better at hunting the gray whale calves,” she said. “It is a pretty amazing event and it all happens within 5 miles of shore.”