MintPress talks to a recent PhD recipient whose work focuses on how “rationalizations perpetuate the notion that American Indians are inherently different from non-natives.”

By Christine Graef, Mint Press News

AKWESASNE, New York — In the two decades since the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) became law, requiring federal agencies and institutions to return human remains and culturally identifiable items, about 38,671 individuals, 998,731 funerary objects, 144,163 unassociated funerary objects, 4,303 sacred objects, 948 objects of cultural patrimony and 822 sacred and patrimonial objects have been returned to their people, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“In terms of NAGPRA since 1990, changes are apparent, for sure, though I have found that this usually involves just subtle changes in language and not real, meaningful change,” said Brian Broadrose, a Seneca descendant who recently finished his doctoral studies at Binghamton University, where he focused on the relationship between anthropologists and Native Americans. “Last I checked, not a single institution with significant quantities of Native bodies and artifacts is in full compliance with the law.”

Despite being flouted as human rights legislation, Broadrose told MintPress that NAGPRA is actually a compromise.

Broadrose spent five years gathering more than 840 pages of data for his dissertation, concluding that the use of language in NAGPRA is deliberate, “in the sense that these categories were not created by Indians, but by those who possess our materials and have a vested interest in not returning it.”

“In its original wording it was strongly resisted by many of the most powerful anthro-organizations out there, including the Society for American Archaeology,” Broadrose said. ”The SAA would only support watered down legislation, whereby they would have exclusive control over the most relevant definitions — for example, a difference between funerary versus unassociated, culturally affiliated or not — and this was very definitely a theme echoed by the troll faction of ‘Iroquoianist’ scholars.”

Funerary objects are considered unassociated when found with human remains if they are not in the possession of a museum or federal agency.

He said the compromised legislation allowed the SAA to switch their scales of analyses, allowing them to make assertions like, “These objects and bodies are not associated or affiliated with the Iroquois, instead of these objects and bodies areassociated or affiliated with American Indians, in general.”

“I regularly found unmarked boxes of bones in various labs at state and private schools here in upstate New York,” he said.

Despite years of efforts to have the region’s ancestors repatriated, there are still some 800 Native American bodies held in New York museums.

“There is a very inadequate old law allowing for the collection of human remains by the State Education Department,” said Peter Jemison, State Historic Site Manager of Ganondagen in New York and Chairman of the Haudenosaunee Standing Committee on the Burial Rules and Regulations.

Jemison said that after years of trying, they found that building consensus across party lines was impossible. Lobbyists representing developers and even farmers prevented legislation from going beyond the committee phase.

“The state is still in possession of human remains; however, we are closer to repatriation,” Jemison said. “The same can be said of sacred objects. The ball is in our court.”

In his 2014 PhD dissertation, “The Haudenosaunee and the Trolls Under the Bridge: Digging Into the Culture of ‘Iroquoianist Studies,’” Broadrose also examined an example of a state rejecting Native educational curriculum that includes their history.

This relationship, he said, is “fraught with hostility and inequality” because of an unfortunate past. Scholars disregarding the significance of American Indian artifacts, unethical and immoral practices continues into the 21st century because “rationalizations perpetuate the notion that American Indians are inherently different from non-natives,” he said.

Curriculum

“Thegroup of ‘Iroquoianist’ scholars consistently minimize the role of the Haudenosaunee in their own Euroamerican culture while overstating the influence of civilized whites upon the Haudenosaunee,” Broadrose wrote in his thesis, which will be published in its entirety by the university this fall.

Dubbed “the trolls,” a term referring to beings from European mythology lurking under bridges, the bridge being what could connect Native people and their history with Euro-Americans and their history, they persistently denied voice to the “Other,” he wrote.

Hiding as if under a bridge, ready to attack those who attempt to cross and meet in the middle, “Many don’t want anything to do with Indians as living breathing people who throw a wrench into the salvage archaeology they continue to practice, which is of course based upon the faulty ‘disappearing Indian paradigm.’”

In the late 1980s the idea for a curriculum supplement was suggested by Donald H. Bragaw, chief of the Bureau of Social Studies Education, at a meeting between New York’s Natives and the State Education Department (SED).

In 1987, a meeting convened between representatives of the SED and the Haudenosaunee Council, including Jake Swamp, Leon Shenandoah, Bernard Parker, Leo Henry, Doug-George Kanentiio, John Kahionhes Fadden, and others. All were in agreement that there were areas that needed work and they were ready to set to the job of supplementing curriculum.

On March 10, 1988 Sen. Daniel Inouye of Hawaii wrote to Fadden, as quoted in Broadrose’s thesis, “The educational project that you and others are undertaking with the New York State Education Department is important to the education of all children, Indian and non-Indian alike”

In what may easily be one of the most positive cooperative efforts between the state and the Haudenosaunee, a 400-page guide for schools, “Haudenosaunee: Past, Present, and Future: a Social Studies Resource Guide,”was drafted.

“The Haudenosaunee authors of the ill-fated curriculum guide wrote their history in a powerful, meaningful work that would have educated young non-native populations in the state of New York about what was here before, and what remains vibrant and in existence today,” Broadrose said.

Then, in 1988, the reviews started rolling in. The SED had solicited evaluations from some 30 experts, including anthropologists, historians and school teachers.

All but five gave positive reviews. The others, however, were “abusively negative,” according to Broadrose. The state dismissed the curriculum guide on the basis of these five, who claimed the Haudenosaunee did not align with what scholars had decided about them, despite the scholars never incorporating the input of any Native American into their research.

Examining the critics, he found, “Arguments of ‘they didn’t use our research,’ to ‘Indians can’t be historians,’ to wanting to save the ideas of the culture while the Indians themselves went extinct detailing charges of reverse racism — that the Haudenosaunee are anti-white — to the charge that the guide authors are political activists with political agendas, to the concern that the proper sources — trolls — were not employed in the guide.”

Finding an assumption of the infallibility of the written Westernized word over other forms of historical recollections, Broadrose said the critics were also “serving as expert consultants and witnesses in court cases involving land or the establishment of casinos, that often encompass the wishes of just single nations or of just single corporate groups.”

“Before anthros resume their seemingly unending study of the Other, perhaps they should devote some research time to studying themselves, their own culture and its role in the production and constructions of pasts,” he said.

The trolls

Collectively, the troll faction of Iroquoianist scholars who rejected the curriculum have been cited by other scholars and themselves 9,263 times, invoking their own authority to perpetuate their own litany, according to Broadrose’s research.

He citedClayton W. Dumont Jr., a member of the Klamath Tribe and NAGPRA specialist, who compared it to a scenario of conquered Americans requesting to have the remains of George Washington repatriated to them.

“After all, Washington had different material culture objects buried with him, different clothing, different technology, and overall lived quite differently than today’s Americans,” he said. “American Indians must, therefore, look and act like the anthropological version of their deceased ancestors, denying them the dynamic nature and adaptability of Euro-American cultures, denying them the ability to change.”

The deliberate complexities in NAGPRA are seen in the Kennewick Man, a skeleton found in July 1996 near Kennewick, Washington. The federally recognized Umatilla Tribe, whose ancestral land he was found on, claimed him as an ancestor.

Archeologists, however, said the Kennewick Man’s age made the discovery scientifically valuable and they claimed there was insufficient evidence to connect him to the tribe.

New York state, meanwhile, does not recognize cultural affiliation for any bodies over 500 years old.

“Simple substitution will show the absurdity of this,” said Broadrose. “Based upon New York law, if I found the remains of a famous European, like Shakespeare, here, I would have the right to collect and study his bones and not be compelled to repatriate to Europeans. After all, Shakespeare wore different clothing, spoke a different variant of English, and had different material culture than Europeans today, therefore, he must not be European. That is the gist of the absurdity of cultural affiliation.”

New York also has no protections in place for burials that are not marked by stone monuments or demarcated in the Euro-American cemetery fashion.

“How is it that basic human rights that all other groups are afforded in the U.S., including

control over ancestral remains and graves, can be compromised or negotiated?” Broadrose asked.

Punk rock inspiration

Broadrose began his dissertation with a question: “What really has changed since the 19th century?”

“The answer is that such differences are in appearance only, not in substance, as the words of the highly decorated, oft-cited troll faction of ‘Iroquoianist’ scholars has made clear,” he said. “The concern is with appearance and not content.”

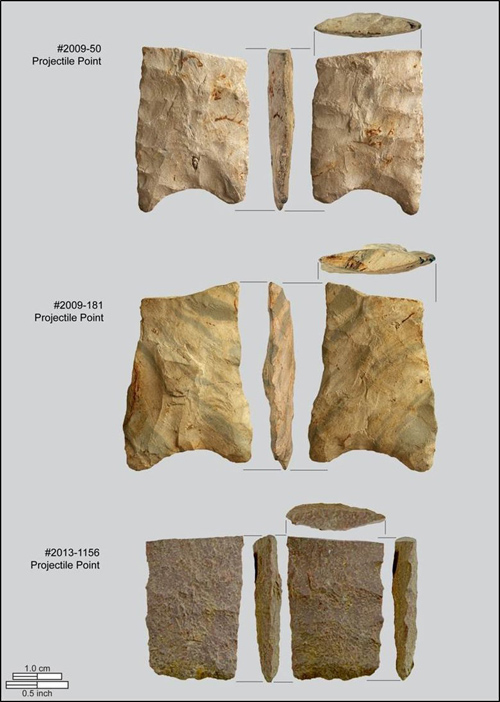

What NAGPRA has demonstrated is that there is no systematic inventory of any removed human and cultural remains, he said. “Most remain unstudied, unsorted, and hidden away in offices, boxes, bags, or as personal curios in scholar’s offices and homes.”

“With no oversight, it is impossible to know the quantity of material taken from American Indians, though we know colonization and such dispossession went hand in hand, so we are talking about a theft of massive scale,” Broadrose said. “And we are just talking about those federally funded institutions and their lack of compliance in compiling the NAGPRA-mandated inventory. We have absolutely no idea the quantity of material that resides in private hands, collected from private lands, exchanged through private collectors.”

Calling it a dispossession of historic magnitude, he said, “In my opinion, [it] easily exceeds the theft of material wealth from Jews and others defined as inferior by the Nazis.”

His research challenges the prevailing notion from the 1980s that archaeologists were objective in reporting the past without inserting their own biases into interpretations. In the face of this critique, researchers now are required to choose a specific theoretical framework as a lens that allows them to mitigate their findings without the question of their profiting.

Broadrose’s theory chapter is titled “Punk Rock: The Destruction of the Spectacle.”

“I spent a lot of youthful time down in the city, jumping around and living the punk rock lifestyle,” he said. “I found some incredible intellectual heavyweights on street corners and makeshift stages, and in my research, I wanted to make clear: academics and scholars do not have a monopoly on complex thought.”

He found that scholars often have tunnel vision, a “me-first” attitude that contradicts their created discourse.

“The punks that I squatted with back in the early 80s, a mix of cast-offs, runaways, and urban Native Americans, understood the Potlatch paradigm,” he said. “In particular, I justified my deconstruction or critical destruction of troll narratives that disempower Indians by looking beyond the obvious — the fire burns, to the reality — the ground becomes fertile for new growth when the flame finishes its consumption.”

In this analogy, Broadrose is the fire.

“Punk rock is discordant and jarring,” he said. “My discourse is modeled after this, loudly interrupting. When the normative narrative is interrupted, the status quo types get agitated and oft times slip up and expose the sort of back stage talk indicative of power inequalities, and I sure wanted to expose that.”

In effect, Broadrose explained, NAGPRA and the scholars are saying, “Yes, we agree that your ancestral bodies and artifacts were removed without your consent, but even though all pre-1492 bodies and artifacts are by definition Indigenous, we still want to keep a bunch of stuff so we can continue our careers as experts on you and your people, and so we can continue receiving funding to measure, record, and pose your stuff to a paying public. So too we will define for you who you are related to and who you are not related to.”

“Behind the scenes I may be marginalized, perhaps tenure or research funding will be denied by any of the 9,000-plus scholars who uncritically cited and accepted the work of troll faction members as fact,” he said.

The burden of proof is on the Native Americans to ask, he said, because otherwise they are dependent on the inventories that institutions which receive federal funding are legally required to compile.

“Few museums complied with NAGPRA, opting to foot drag and draw out the process,” he said. “Why have they not been inventoried? I am a proponent of Indians making surprise visits to anthropology departments and museums to see what might be found. A box of what are clearly human remains in an unmarked box under the lab table of a biological anthropology classroom in a federally funded institute, is, in fact, a violation of NAGPRA and warrants further investigation.”