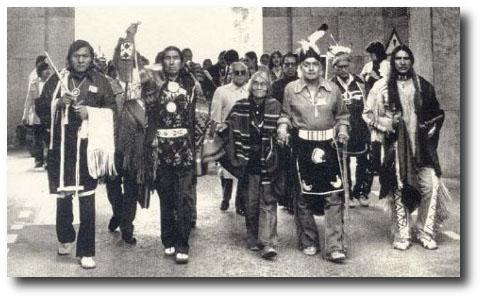

Photo/ Roger Werth, TDN

By Brooks Johnson, The Daily News

In a fight for federal recognition, the Chinook Indian Nation and Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes are each bringing their own history books to the debate.

A bill introduced in Congress this year would recognize Oregon’s Clatsop-Nehalem tribes, granting them the same rights to sovereignty and self-determination as the more than 550 other federally recognized Native American tribes.

That doesn’t sit well with the leaders of the Chinook Nation — 3,000 members comprising Cathlamet, Lower Chinook, Wahkiakum, Willapa and Clatsop tribes. They say the Clatsop-Nehalem are historically part of the Chinook Nation and that recognizing them separately would undercut the Chinooks’ 160-year-old drive for federal recognition.

“We want people to know we are the Clatsop people, and when it comes to that tip of Oregon there (the Lower Columbia), we’re there and we’re not going away,” said Sam Robinson, vice chairman of the Chinook Nation. “To have a group just come out of nowhere is a little bit disturbing.”

But Clatsop-Nehalem Council member David Stowe said the group hasn’t come out of nowhere, and that the history of the confederated tribes has been well-documented.

“The Chinook have a history of sour grapes,” Stowe said. “… but our restoration doesn’t impact the rights of anybody. They’ll have exactly what they have right now, and we hope they get restoration as well.”

At stake for both tribes is the ability to become sovereign and restore rights to land, hunting and fishing rights as well as partake in services offered by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Competing press releases sent out in September from both tribal councils disagree on the history of the Clatsop people.

The Chinook Nation says its 1950 constitution was drafted by its five member tribes in reference to 1851 treaties, and the federal government recognized the Clatsop’s relationship with the Lower Chinook in 1958.

“The history with the Clatsop-Nehalem is pretty fresh, compared to thousands of years of history the Chinook folks have,” Robinson said.

But the Clatsop-Nehalem say that despite centuries of trade along the Columbia River and marriages with other tribes, the Clatsop have been a distinct entity since before Europeans arrived.

About 25 percent of Chinook enrollment is Clatsop, according to the Chinook Nation, and any splintering could lessen those numbers.

“We just feel it’s not right. Because they won’t take all of our folks” for federal recognition, Robinson said.

The Clatsop-Nehalem don’t see the problem, however.

“Clatsop that are enrolled with the Chinook, Quinault, Grand Ronde or Chehalis tribes or other tribes are free to choose their enrollment status,” the Clatsop-Nehalem press release reads. “Our restoration will not change their status or member benefits in any way. We have no desire to make any claims of any kind in the Chinook homeland in Washington.”

Those of Clatsop descent may also have other tribal connections in their bloodline. Robinson gave the example that he is descended from Lower Chinook, Willapa Chinook and Chehalis tribes. The amount of ancestry needed to enroll in a tribe is up to individual tribes’ governments.

BIA Northwest Regional Director Stan Speaks says it’s impossible to know what will happen before recognition is granted, and it is “premature to think fellow members are going to abandon one group and go with the other.”

The restoration bill before Congress, introduced by Rep. Suzanne Bonamici (D-Ore.), asks for little more than recognition. Land, hunting and fishing rights have all been left out of the equation.

“That’s very contentious,” said Stowe, the Clatsop council member. “(Asking for more) creates a whole whirlwind and lessens our chances of restoration. At the end of the day what’s important to us, what’s important for our identity is recognition of our tribe.”

The term restoration is used by both sides of the debate. The Clatsop and Nehalem tribes were “terminated” by the federal government in the 1950s under the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act. That severed ties between the government and the tribes in a new policy toward Native Americans. The policy was later reversed for many of the terminated tribes, excepting the Clatsop and Nehalem. Stowe says the act of termination is recognition in and of itself because the Clatsop and Nehalem tribes are listed in the law.

The five tribes of the Chinook Nation — including the Clatsop — were recognized at the end of the Clinton administration, only to have the status revoked 18 months later by the Bush administration.

“We felt it was an injustice for them to be recognized and have it yanked form them, that was horrible, and it was equally an injustice we were terminated in 1954,” Stowe said.

The argument between the groups is centered around those living north or south of the Columbia River, though both sides agree that the divide can be arbitrary.

Dick Basch, the vice chairman of the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes, supports efforts to get his tribes recognized, but he is “saddened” by the fighting it has caused.

“We are Lower Columbia Indians that should be supporting each other and working for the benefit of all of us,” Basch said. “We’re all Indian people and just because some of our families went south and others went north doesn’t mean that we have to battle each other.”

Robinson and the Chinook agree on the principle of unity.

“Some folks say, “Well they’re Oregon Clatsop or they’re Washington Clatsop.’ … But the river wasn’t a divider — it was just a highway for us.”