— image credit: Richard D. Oxley / North Kitsap Herald

By Richard Walker, North Kitsap Herald

LITTLE BOSTON — Pullers in the 2014 Canoe Journey are in for a long one, a 500-miler to the territory of the Heiltsuk First Nation — Bella Bella, British Columbia. They’ll be richly rewarded for the experience.

They’ll travel through territory so beautiful it will be impossible to forget: Rugged, forested coastlines; island-dotted straits and narrow, glacier-carved passages; through Johnstone Strait, home of the largest resident pod of orcas in the world; along the shores of the Great Bear Rainforest, one of the largest remaining tracts of unspoiled temperate rainforest left in the world.

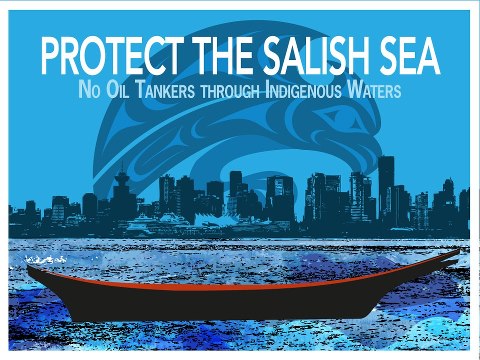

They’ll also travel waters that are increasingly polluted and under threat.

Pullers will travel the marine highways of their ancestors, past Victoria, which dumps filtered, untreated sewage into the Salish Sea. They’ll travel the routes U.S. energy company Kinder Morgan plans to use to ship 400 tanker loads of tar sands oil each year. Canoes traveling from the north will pass the inlets leading to Kitimat, where crude oil from Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline would be loaded onto tankers bound for Asia; Canada approved the pipeline project on June 17. Canoes from the Lummi Nation near Bellingham will pass Cherry Point, a sacred and environmentally sensitive area where Gateway Pacific proposes a coal train terminal; early site preparation was done without permits and desecrated ancestral burials.

Young activist Ta’kaiya Blaney of the Sliammon First Nation sang of her fears of potential environmental damage to come in her song, “Shallow Waters”:

“Come with me to the emerald sea / Where black gold spills into my ocean dreams.

“Nothing to be found, no life is around / It’s just the sound of mourning in the air.”

Native leaders hope the Canoe Journey calls public attention to the fragility of this environment.

“We need to wake up to what’s happening to Mother Earth,” said Cecile Hansen, chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribe and a great-great-grandniece of Chief Seattle.

“We’re the indigenous people of the land. If anybody should be raising that flag, it should be Native Americans.”

Suquamish Chairman Leonard Forsman is pulling in the Suquamish canoe to Bella Bella.

“The Journey is a cultural, spiritual, ceremonial and social event,” he said. “The Journey can provide a platform for expressing our Tribal values that include habitat protection and improving or protecting water quality. Decisions on if and how to participate in political expressions are decisions made by each Tribal canoe family individually.”

“The Journey is a cultural, spiritual, ceremonial and social event,” he said. “The Journey can provide a platform for expressing our Tribal values that include habitat protection and improving or protecting water quality. Decisions on if and how to participate in political expressions are decisions made by each Tribal canoe family individually.”

Micah McCarty is a former chairman of the Makah Nation and a member of the board of First Stewards, which seeks to unite indigenous voices to collaboratively advance adaptive climate-change strategies.

He sees the Canoe Journey as an exercise in Tribal sovereignty, particularly in the realm of environmental education.

U.S. v. Washington, also known as the Boldt decision, reaffirmed that Treaty Tribes had reserved for themselves 50 percent of the annual finfish harvest; a later court decision extended that to include shellfish. In addition, Boldt established the state and Treaty Tribes as fisheries co-managers.

“The state-Tribal co-management relationship relative to … US v Washington is more effectively built on Tribal governments assuming more and more of the federal trust responsibility in the spirit of self-governance and by directly investing in Tribally determined education,” he said.

“Native sovereignty is as good as it is practiced and implemented. No one else can do this for us, and the best investment in sovereignty is education by Indian sovereign design — including curriculum pertaining to treaty resource damages [caused by] climate change and carbon pollution, particularly in the form of carbonic acid.”

The Canoe Journey is itself a tool to monitor the health of the sea. In each Canoe Journey since 2008, in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey, several canoes carry probes that collect water data and feed the data into a recorder aboard the canoe. The data measures water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH and turbidity.

The USGS is using the data to track water quality and its effects on ecosystem dynamics. You can read the results from 2008-2013 at http://wfrc.usgs.gov/tribal/cswqp/.

It’s the Canoe Journey’s first return to Bella Bella since 1993, when canoes made the long journey north to fulfill a vision of Canoe Journey founders Emmett Oliver and Frank Brown in 1989 after the Paddle to Seattle that was held as part of Washington’s centennial celebration. That 1993 journey sparked a revival in indigenous travel on the marine highways of the ancestors.

En route to the final destination, canoes visit indigenous nations along the way, each stop filled with sharing: traditional foods, languages, songs, dances and teachings. Pulling great distances can test physical and mental discipline. Traveling the way of the ancestors can be a spiritual experience, and songs often come to pullers on the water.

This journey will be as challenging as the 1993 journey. From Little Boston, canoes travel west to Port Angeles, then cross the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Vancouver Island. They’ll travel north along the east side of the island to Port Hardy, then cross big water from Vancouver Island to the B.C. mainland. As they head north, they’ll pull through passages and channels and will have to time each transit right so they’re not pulling against tides.

More than 100 canoes participated in last year’s journey to the Quinault Nation. The distance and isolated destination in this year’s journey requires a month off for peninsula and South Sound pullers and support crews. Heiltsuk is expecting 54 canoes.

Three Suquamish canoes and one Nisqually canoe departed from Suquamish on June 17, moored overnight in Kingston, then arrived at Point Julia on June 19. Those canoes and one from Port Gamble S’Klallam will depart for Jamestown S’Klallam on June 20, then meet up with canoes from Pacific Coast Tribes at Elwha Klallam. Canoes will cross the Strait of Juan de Fuca on June 22 for Vancouver Island and points north. All are scheduled to arrive in Bella Bella on July 13.

Among those traveling part of the journey: Marylin Bard of Kingston, Emmett Oliver’s daughter. She will travel in a five-person river canoe that was gifted to her father by the Quinault Nation last year.

“We will be traveling the ‘Old Way,’ carrying our own supplies on the canoe,” she wrote in an email. “No support boat, no hosting, just camp along the way. [We] plan to fish and crab for food.”

Get more information about the 2014 Canoe Journey/Paddle to Bella Bella: www.tribaljourneys.ca.