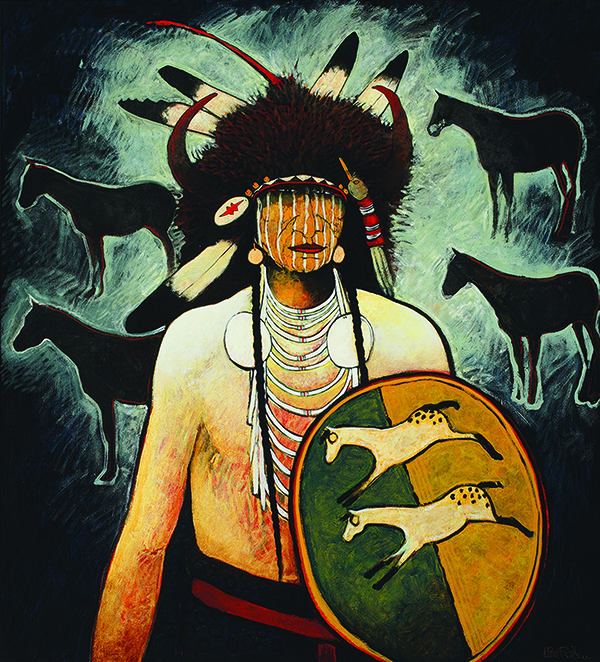

Buffalo Horse Medicine, 2007, Mixed media

The Crow people have enduring relationships with horses. Paraded at the annual Crow Fair Celebration and other special events, horses adorned in beaded regalia demonstrate their value and importance to the Crow Nation. In Buffalo Horse Medicine, Kevin Red Star depicts horses that are an important breed for buffalo hunting. Red Star signifies a connection between this man’s identity as a buffalo hunter and his strong relationship with horses.

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

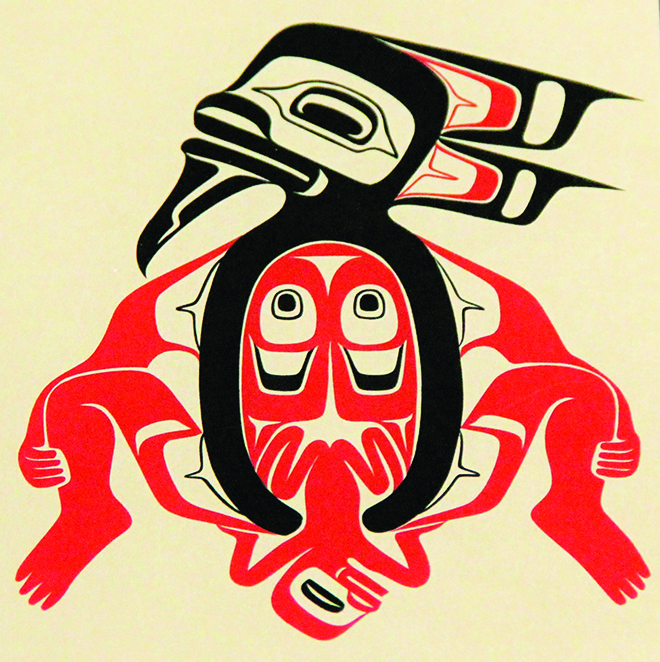

Many portraits of Indigenous people by non-Native artists romanticize, stereotype, or appropriate Native people and cultures. Contemporary Native artists are actively deconstructing these myths and preconceptions about their culture through the use of art. In fact, many modern-day artists use a dynamic combination of materials, methods and concepts that challenge traditional boundaries and defy easy definition.

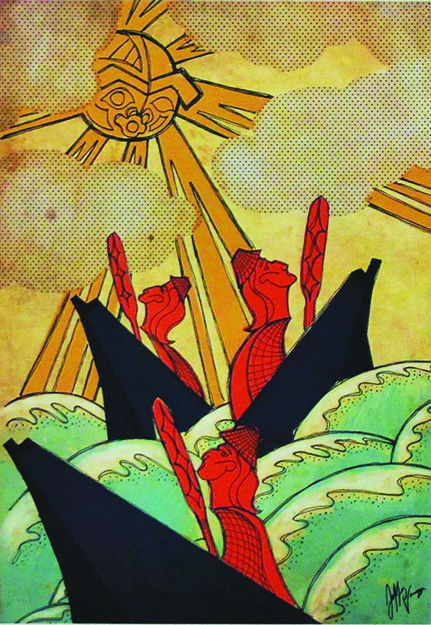

Indian Canoe Party, 1906, Watercolor on paper

Great Slave Lake is in the Northwest Territories about 1,200 miles north of the Montana-Canada border. When Russell was 24-years-old, he spent six months in the Northwest Territory. It is possible that this painting is based on his travels.

Russell paints with a romanticism and nostalgia for what he considered the Old West. His idealized paintings of Natives are ripe with metaphors. In the early 20th century, most of America was concerned or convinced that Native cultures would be extinct. For Russell, the setting sun represented this false view.

Tacoma Art Museum’s newest exhibition “Native Portraiture: Power and Perception” gives voice to Native people and communities to show their resiliency and power over the ways in which they are portrayed and perceived. Native tribes aren’t uniform, they are diverse with a variety of distinct characteristics. As such, the artists in this show have taken on varied points of view while sharing their voice. All are well executed and demonstrate that you can’t pin Native art into a single category.

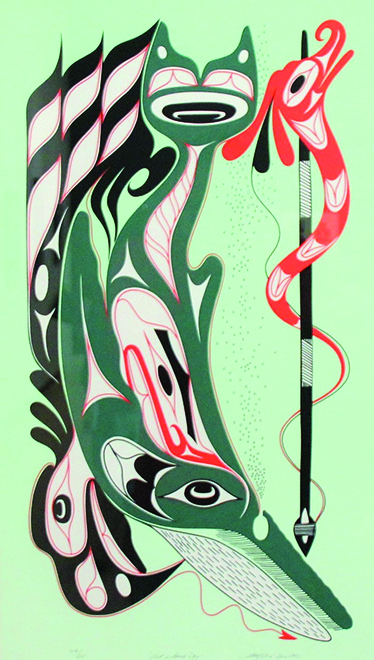

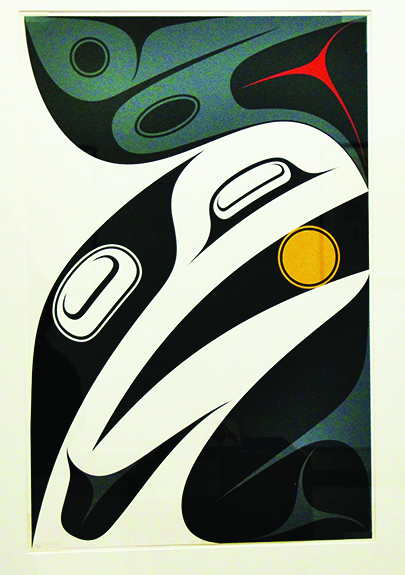

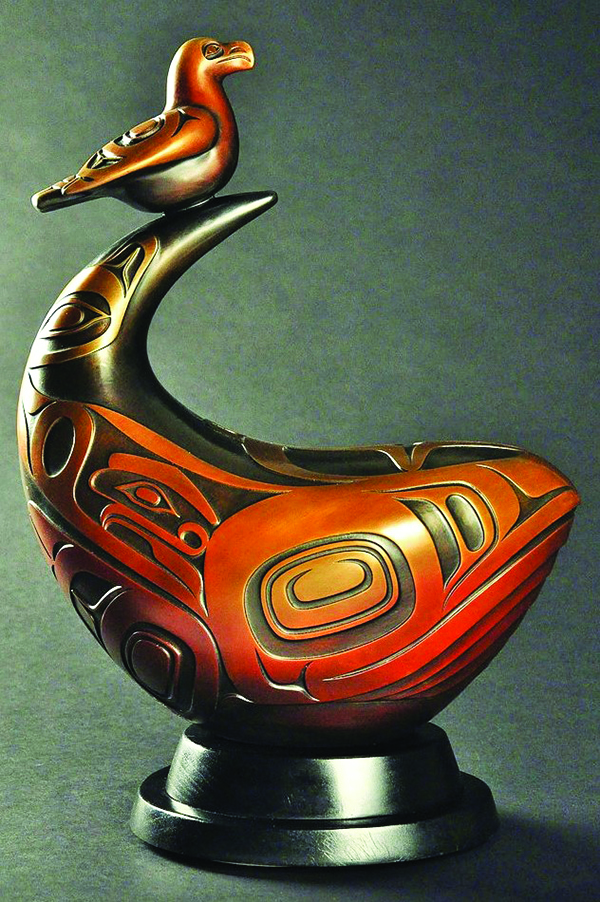

Whale & Eagle, 2013, Limited edition patented bronze

Artists capture the true appearances of the animals by highlighting anatomy and form. Bronze sculptures typically appear on a base without any background images, which places further emphasis on the shape and individuality of each creature rather than on the scene or setting. Through his sculpture, Preston Singletary invites viewers to look more closely at animals and foster a sense of awe and wonder.

“We can now say, let’s look at this artwork and use a contemporary lens to unpack where these artists are coming from and why they painted the work in this manner,” explained Faith Brower, exhibit curator. “We hope to inspire visitors to explore both controversial issues of appropriation and cultural imagery, and to think differently about Western art and how it relates to their lives and communities.”

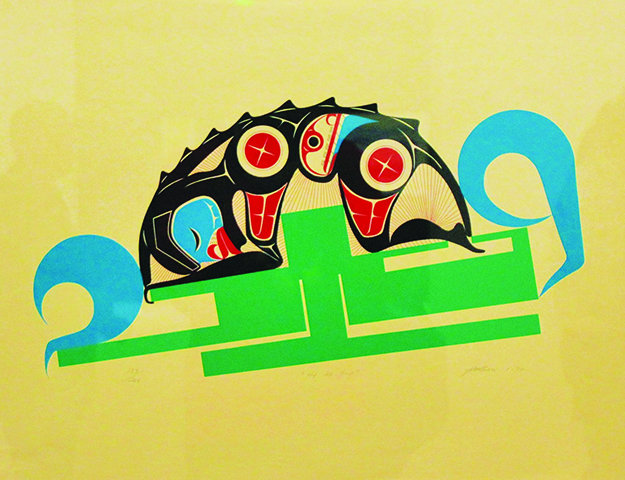

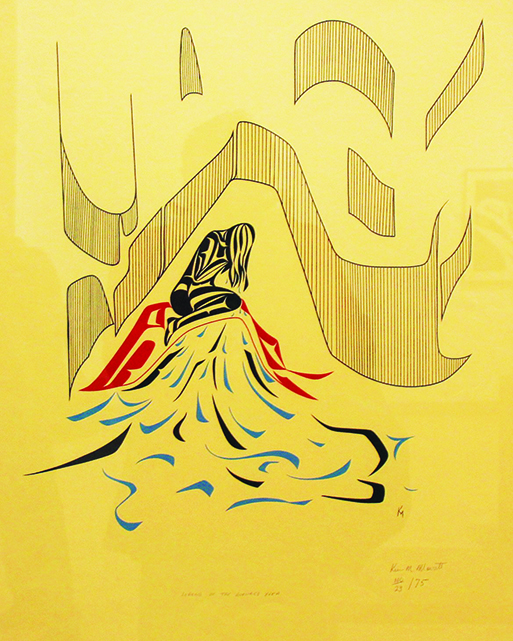

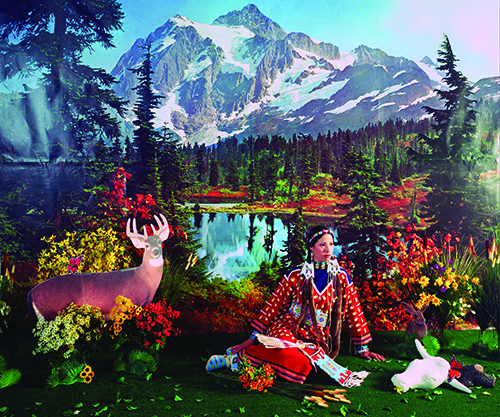

Indian Summer – Four Seasons, 1996, Archival pigment print

When visiting natural history museums, Crow artist Wendy Red Star was struck by the displays that treat Native people as inanimate remnants of the past. She reclaims these troublesome dioramas by humorously staging a fake museum display in which she wears an elk tooth dress, hair wraps and beaded moccasins while sitting on artificial grass surrounded by fabricated plants and animals. Simulating a mountain lake scene, this image uses humor and irony to address issues of stereotyping and romanticizing Native people today.

“Native Portraiture: Power and Perception”, on display through February of 2019, highlights work by Native artists who address issues of identity, resistance and reclamation through their powerful artwork. The artists ask us to reconsider images of Indigenous people because certain reoccurring themes, such as the “vanishing Indian” and “noble savage”, have led to centuries of cultural misunderstandings.

Welcome Figure, 2010

Cedar, steel, graphite and magnets

The 20-foot-tall Welcome Figure stands fixed in Tacoma’s Tollefson Plaza, where a Puyallup tribal village had once stood. From acquiring and transporting a suitable wind-fall cedar log, to devising a metal support system, to carving, assembling, and painting the figure, the work stands as a time-honored sculpture that greets people on Coast Salish lands. Funded by the City of Tacoma, the Puyallup Tribe, and Tacoma Art Museum, the figure is carved from a single log and marks the participation of the tribe and Coast Salish people in contemporary society. Installed on September 13, 2010, the Welcome Figure is a powerful reminder that we are on Indigenous land.

“What’s happening now is museums are realizing that they have a problem and that problem is that they don’t have the Native American perspective,” said exhibit artist Wendy Red Star. “All the culture has been mined and been talked about by non-Natives. Now, there’s a switch where that body of work works really well as sort of being an institutional critique piece. It tends to fit, to help articulate that in an exhibition like this.”

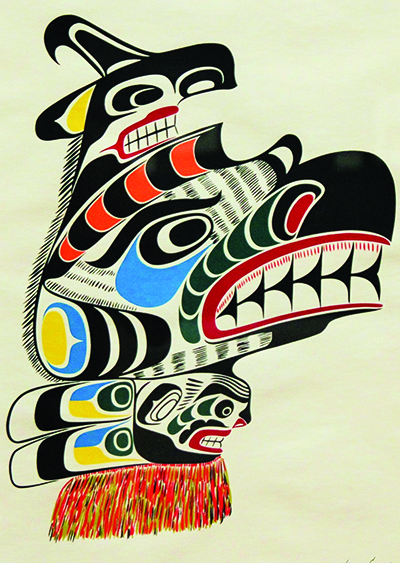

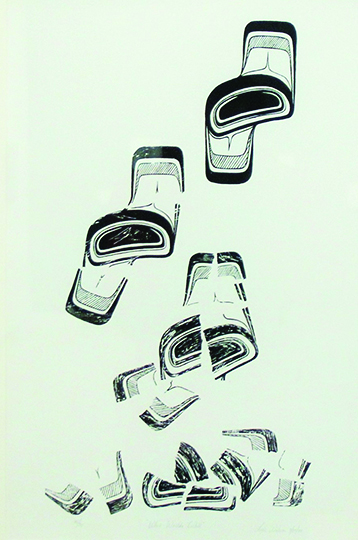

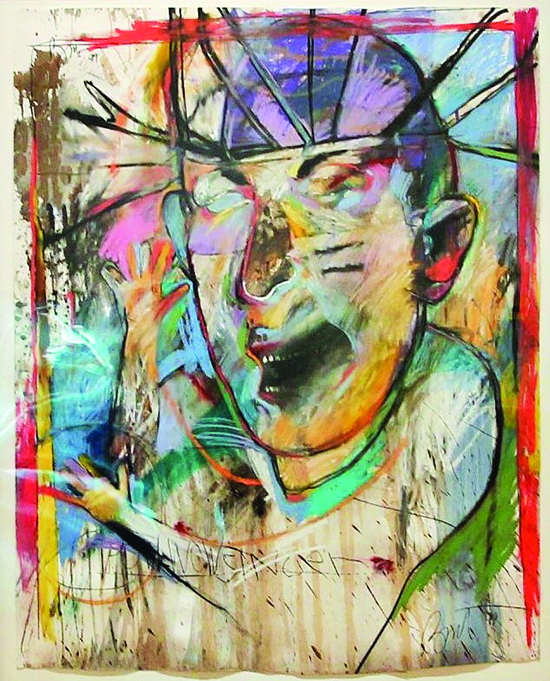

Old Time Picture I, 1999

Mixed media on handmade paper

Wiyot artist Rick Bartow is known for his powerful, vibrant and expressive images of people and animals. His work is honest and provocative depicting emotions that set it apart from stereotypical representations of Native people and cultures. Rather than glorifying a stoic person in a headdress, Bartow depicts the range of emotions that people feel through this depiction of a man. The title further suggest Bartow’s challenge of the stereotypical depictions of Native Americans.