By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

“We are proud and excited to celebrate the installation of traditional native artwork on the waterfront of Seattle. We are especially thrilled about the completion of the art project by our treasured Suquamish elder and carver Randi Purser. Her work, that is part of another piece on Bainbridge Island, reflects our ancient presence on the waters between Seattle and the Kitsap Peninsula, named after two of our ancestral leaders.

“We thank the City of Seattle and the Friends of Waterfront Park for their commitment to this project honoring our heritage and traditions and the entire art team for their dedication and creativity.”

Those words were shared by Suquamish Chairman Leonard Forsman as he joined civic and tribal leaders at an official dedication for a highly-anticipated, publicly-sited art installation that spans multiple blocks along the revamped Seattle waterfront. Flanking the Seattle ferry terminal at Pier 52 are 22 pairs of sculpted Douglas Fir posts and beams representing the skeletal structure of a traditional longhouse.

The eye-catching longhouse installation is intentionally minimalist. With no walls, roof or doors, it serves as a potentially thought-provoking sculptural concept for millions of pedestrians who are embarking or disembarking from one of the terminal’s popular Jumbo Mark II class ferries. That’s not even accounting for all the usual and accustomed tourist foot traffic that routinely floods Seattle’s waterfront.

The visionary artist behind the installation’s design is Oscar Tuazon. He is known for his use of minimalism and conceptualism in using natural materials to create large scale sculptures in populated urban areas. He’s titled his latest, three-block-long art installation To Our Teachers.

“To Our Teachers is a framework for the future,” explained Oscar, who grew up on the Suquamish Tribe’s Port Madison Reservation. “Welcoming people at the edge of the water, the procession of post and beam frames are the beginning of a structure you can imagine in your mind. Inspired by the living tradition of deqʷaled, the distinctly Coast Salish house post that unites sculpture and architecture, the construction is designed to support the continuous evolution of the artistic culture unique to Seattle.

“Working on this project has profoundly changed how I think about art,” he continued. “The opportunity to work with Randi Purser (Suquamish) and Tyson Simmons and Keith Stevenson (Muckleshoot) and create a structure to showcase their work has really expanded my understanding of what artists are capable of through collaboration. Together we can create spaces for community. This is why I think of To Our Teachers as a structure continuously being built— this is not the final form of the work, it is just the beginning of something bigger than me.”

Seattle is a hub for urban Natives whose roots extend across Washington State reservations and beyond. That spirit of connectedness is represented in this pier enhancing artwork. As Oscar stated, he collaborated with tribal carvers from Suquamish and Muckleshoot. Those carvers created two towering cedar house posts that are seamlessly imbedded into both longhouse entrances. Each house post is filled with deep-rooted significance for not just the artists’ home tribes, but all those urban Natives who call Seattle home.

Tyson Simmons and Keith Stevenson carved the southernmost house post, which they’ve named Honoring Our Warriors. “This warrior figure was inspired by the carvers’ warrior-uncle,” explained the two carvers. “Yet, it represents the valor and sacrifice of all our warriors to secure our land, our salmon, and our native walk of life.

“Our warriors all carried spiritual gifts that cloaked them with strength and protection,” they continued. “Fisher is depicted below the warrior figure to represent our warriors’ myriad powers without disclosing any of their individual powers. We carry the responsibility to remember and tell our stories. The work is guided by our teachings. Our ancestors prayed for us. They didn’t know who we would be, yet they prayed for us.”

being held by his mother Sholeetsa.

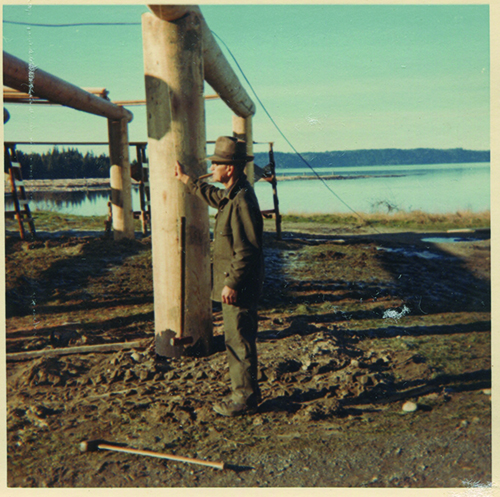

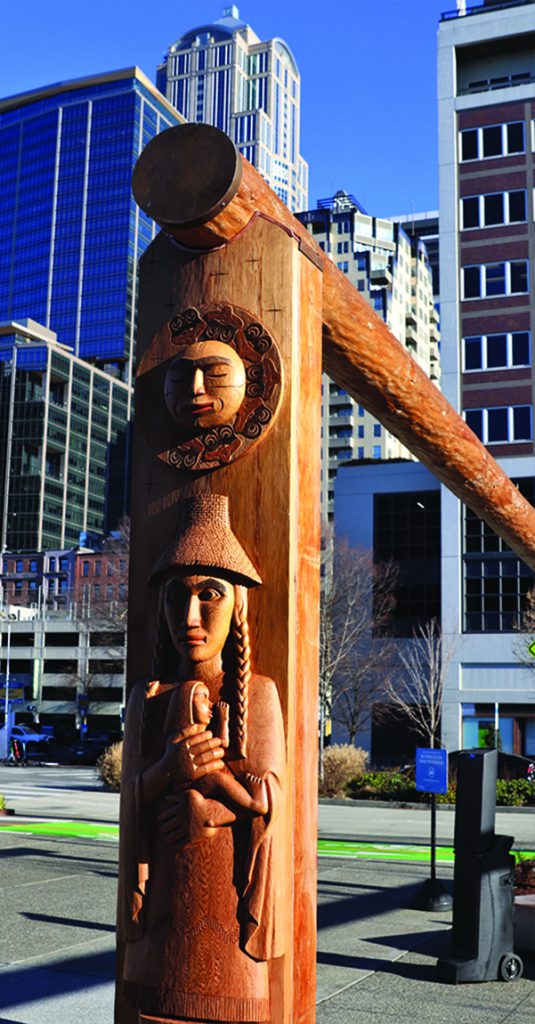

At the northernmost entrance is Suquamish elder Randi Purser’s house post. She’s dubbed hers ʔəslaʔlabəd kʷədi bəḱʷ dadatu, which translates to Looking at All Tomorrows. Drawing inspiration from the city’s namesake, which translates to Looking at All Tomorrows. Drawing inspiration from the city’s namesake, Chief Seattle, she paid homage to not just the legendary chief, but his lifegiving mother as well.

“Sholeetsa was the mother of Chief Seattle. Protected within her loving embrace is her son Chief Seattle as a baby,” described Randi to the crowd who looked upon her carving. “On her dress is a design of the unfolding fern, which represents new life. Above her is the moon surrounded by frog heads. The frogs represent a time of change as they sing the winter away and the spring in. As a whole, this carving represents the people of today standing on the cusp of change.”

What’s on the other side of that cusp of change is subjective to any one of millions of pedestrians who every month will assuredly walk on the Seattle waterfront, pass the ferry terminal, and have an infusion of Coast Salish culture enter their peripheral vision.

However, as the artists involved shared, there is a unified desire that the change be reflective of recognizing the past that got us here and honoring still thriving Coast Salish communities in the collective future we all share. In commissioning this layered piece of public work, Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront understood and shared the artists’ vision.

“As we transform Seattle’s waterfront, it has been important to us that we honor its history and move forward with intention,” said Angela Brady, Office of the Waterfront & Civic Projects Director. “We want visitors to remember that Waterfront Park stands on the lands and shared waters of the Coast Salish Peoples, whose ancestors have resided here since time immemorial. The original inhabitants of the region built structures along the shore. These new artworks honor the important cultural history of the waterfront. I hope they encourage visitors to reflect on how we, as a city and a region, hold space for Indigenous communities, not just in our past but in our future.”