By Karen Herzog, Milwaukee Wisconsin Journal Sentinel

Green Bay — Students at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay who want to learn about the state’s American Indian tribes don’t turn to books, but to tribal elders who live on nearby reservations and keep office hours in Wood Hall.

It’s a unique opportunity for any student on campus to sit face-to-face with a tribal member who is a repository of knowledge and wisdom passed on to him by his elders — everything from tribal beliefs and teachings to tribal culture, language and faith in the Great Spirit, the Creator.

Green Bay is within 100 miles of five Indian reservations for the: Oneida, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Stockbridge-Munsee and Mole Lake. The Oneida reservation is on the city’s outskirts.

It would be logical to assume UW-Green Bay draws a large number of Native American students with its proximity to tribal lands. But like the rest of the UW System, UW-Green Bay’s enrollment of Native students is flat, while the numbers of other underrepresented minorities are growing.

Last fall, only 98 of UW-Green Bay’s 6,667 students were Native American. Systemwide, 679 of the 154,446 undergraduates at campuses across the state identified themselves as Native Americans — 0.4% of the total enrollment.

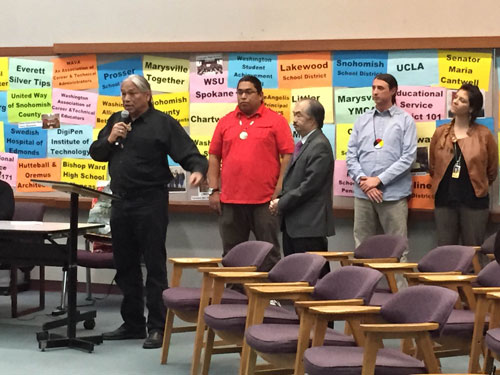

In an effort to better understand why that is — and what can be done to help more Native American students in Wisconsin earn college degrees — the UW System Board of Regents invited leaders of the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council to join them Friday at an unprecedented meeting in Stevens Point.

It may be the first time tribal leaders have sat down with leaders of the state’s system of higher education, UW officials said. UW Regent Ed Manydeeds and UW System President Ray Cross attended a Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council meeting in July to extend the invitation.

“The history that happened to these people didn’t happen that long ago,” said Manydeeds, the first Native American regent and a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

“They’ve never been asked anything; they’ve just been directed,” Manydeeds said. “They are entitled to the same careful relationship-building as others. We owe it to these people, like everyone else, to have a chance to be educated. We want them to help us help their students be successful.”

Wisconsin’s Native American population is about 1% of the total population, but the numbers have increased 12.6% since the 2000 census.

The state has 11 federally recognized tribes. About 45% of the Native American population is in the state’s metropolitan areas; 13.7% (7,313 people) lived in Milwaukee County in 2008.

UW-Oshkosh last year had the UW System’s highest Native American enrollment (117), followed by UW-Milwaukee (114), UW-Madison (112) and UW-Green Bay (98).

The Wisconsin Technical College System has about twice as many Native American students as the UW System. The state’s two tribal colleges have about the same as the UW System.

Increasing Native American enrollment may require a shift in campus culture, according to tribal elders at UW-Green Bay. There’s a need for non-Native students to understand and respect Native American culture, and a need for Native students to feel like they fit in on college campuses.

UW-Green Bay has a First Nations Studies program that focuses on Wisconsin’s Native American tribes and bands, and is considered a model for building understanding and respect of tribal cultures. It reaches students who are interested in a First Nations Studies major or minor, students learning to be teachers, and students in general education classes such as history.

David Voelker, an associate professor of Humanistic Studies and History, set out several years ago to fuse First Nations content with his American history classes because he wanted to teach in a way that was relevant and respectful. He has learned from tribal elders and colleagues in the First Nations Studies program.

“Part of it is reminding everyone that First Nations still exist,” said Voelker, who grew up in Indiana and had only a rudimentary exposure to Native American history while working toward his master’s degree and doctorate in American history.

“Just having more knowledge and respect is important,” Voelker said. “It’s hard to be respectful if you’re ignorant.”

Tim Kaufman, chair of the Education Department, considers the elders in residence the heart and soul of the Education Center for First Nations Studies. Students learning to be teachers take courses in First Studies and meet with tribal elders to help them better understand Wisconsin’s tribes so they can teach specific content in K-12 schools, as required by Wisconsin Act 31.

“One of the real focuses on this center and the program is interdisciplinary connections,” Kaufman said.

The First Nations Studies program teaches history, sovereignty, laws and policies, and indigenous philosophy. Students also learn about the contemporary status of bands and nations, according to Lisa Poupart, associate professor of Humanistic Studies, First Nations Studies and Women’s Studies.

Poupart is chair and adviser for the First Nation Studies program, and is an enrolled member of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Anishinabe (Ojibwe).

Menominee elders David “Napos” Turney Sr., and Richie Plass enjoy sitting down with students who stop by the First Nations Studies office in Wood Hall to ask questions. Many of the students are non-Native, and know nothing about Native culture.

They talk about everything from the degradation of school mascots to cultural stereotypes.

For example, “everybody thinks if you’re Native American and have a casino, you’re rich,” Plass said.

Plass, a published poet, was an Indian mascot in high school in 1968, and remembers traveling to another school where students threw banana peels, orange peels and paper cups at him. Then they spit on him.

“To me, there’s no honor in having people laugh at me, throw food on me and spit on me,” he said. Plass travels around the country with an exhibit he created on Native American imagery, showing both the “good” and culturally correct items from Native American culture and the “not so good” images, such as school mascots.

Turney said when he meets students, he asks who they are, where they are from and whether they have ever been around Native Americans. He is a Vietnam War veteran. He also works with students in Green Bay schools as a traditional elder in residence for the Title 7 cultural program.

Turney teaches Menominee at UW-Green Bay and in Green Bay public schools. Today, there are only five first-language Menominee speakers on the tribal rolls of 9,000 people, he said.

Turney and Plass sat deep in thought when asked why there aren’t more Native American students on UW campuses.

Part of it is the devastation of addiction on reservations, they said. “There’s some very smart Indian kids who didn’t graduate from high school because they were cutting the rug,” Plass said.

Tribal colleges on tribal lands have helped raise the numbers of college educated American Indians, he said.

Some Native Americans don’t realize they need a college degree until they are adults, Turney said. He didn’t earn his bachelor’s degree until he was 50.

Why did it take him so long?

“I didn’t think I was ready for it and I didn’t think I could do it,” he said. “When I was young, I also was worried they would change my way of thinking or who I was if I went to college. I was really proud of who I was.”

It also can be hard for Native American youths to fit in on college campuses because there are so few students like them, Turney and Plass said.

Plass said many youths just don’t want to leave the reservation — sovereign land where they can hunt and fish whenever they want.

And then there’s racism. “That’s a very uncomfortable subject to come out,” Plass said.

Turney recalled that the Inter-tribal Student Council on campus several years ago met resistance from the non-Native student government when they sought funding to serve Native food at a powwow. The Native students were angry and chose not to have the powwow as a friendly boycott.

They brought the powwow back two years ago, when UW-Green Bay was recognized among the top schools in the U.S. for Native American students, said Turney, who was the group’s adviser.

Native students look at the tribal elders in residence as campus allies. “We have to help non-Native students learn about us,” Turney said Native students tell him.

Turney said he doesn’t preach going to college, but believes the key to success for Native American students is knowing who they are and taking pride in their culture.

“If your roots are strong, there’s no wind that can blow you over,” he said.