By Jay Daniels, Round House Talk

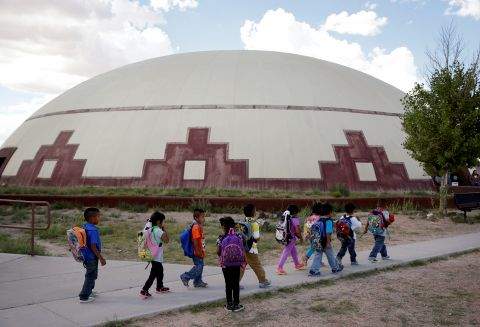

Haskell Indian Nations University (“Haskell”) is the premiere tribal university in the United States offering quality education to Native American students. Haskell’s student population averages about 1000 per semester, and all students are members of federally recognized tribes. Haskell’s faculty and staff is predominantly native. Haskell offers Associate and Bachelors degrees. Haskell’s historic campus is centrally located in Lawrence, KS in what is known as Kaw Valley.

Today, after more than 130 years of existence, Haskell is experiencing extreme funding shortfalls and reducing the necessary funding to provide educational as well as student extracurricular activities, such as athletics, educational field trips and generally preparing students for life after degrees are obtained.

Summary of Haskell’s Sports History:

In 1884 Haskell initially opened its doors to American Indian students as Haskell Industrial Training Institute. Today Haskell has emerged from those early years as a vocational/commercial training institute that initially offered a 5th grade curriculum, followed by an 8th grade curriculum, and by 1921 a full-scale 12th grade high school curriculum and maintained until 1965. In 1970 Haskell became an accredited junior college and by 1994 Haskell attained university status when it began offering both associate and baccalaureate degrees. During the existence of Haskell, there have been consistent academic/training alterations and changes to the methods and emphasis of training and teaching at Haskell (manual training courses, agricultural training, commercial courses, normal educational development, grade school/primary school education, high school development, domestic arts, domestic sciences, junior college, and finally university status). But the one constant has been athletics and its role as a viable part of Haskell’s development.

Haskell’s first organized sport against competitive opponents was football which began in 1896 and from 1919 to 1930 Haskell developed one of the most successful athletic programs in the school’s history recording a won/loss record of 94-31-6[JD1] . Haskell competed collegiately during this time and played some of the most formidable teams during that period of time including Kansas University, Oklahoma University, Notre Dame, Oklahoma A & M University, Tulsa, Nebraska, Boston College, Minnesota, and Bucknell.

Most nationally notable football game

The Hominy Indians were an all American Indian professional football team, meaning The Real Americans, located in Hominy, Oklahoma. The financiers were from Hominy, the Osage Tribe, and other tribes – the players were from all over. On December 26, 1927, they defeated the National Football League New York Giants who were titled world champions three weeks prior to the game with the Hominy Indians. Hominy was short handed of players and asked Haskell if they had any players willing to play with Hominy. Several eagerly accepted and were an integral part in helping Hominy in beating the NFL Giants 13-6.

Notable Haskell Native American Athletes

John Levi, an Arapaho tribal member is noted as the greatest runner back during the era, from 1921 to 1924 (He was named first team All-American in 1923),

Tommy Anderson, a Muscogee Creek stood as the premier running back in 1919, but the greatest team is believed to be the 1926 undefeated team that went 12-0-1 and was the first team to play in the newly built 10,500 seat stadium built with the exclusive donations of American Indian people. The largest contributors, were Osage and Quapaw tribal members who at that time were beneficiaries of oil and other mining resources.

The 1926 team had the benefit of what may have been the greatest all-around backfield in Haskell’s history including Elijah Smith who was the fastest of the running backs; George Levi performed as both an inside and outside runner; Mayes McClain served as the fullback and the team’s leading scorer (scoring a record 253 points, a scoring record that stood for 80 years); and Egbert Ward, ran the quarterback position.

In addition to the potent running and passing utilized by the 1926 team the team also had two of the best linemen in the nation. Tiny Roebuck and Tom Stidham (Mayes McClain would lead the nation in scoring in 1926 and his record of 253 points scored in a season was a record that stood for nearly 80 years. Tom Stidham would eventually coach collegiately at various universities including football at the University of Oklahoma. The 1926 team ended the season considered among the top collegiate programs in America.

In the 1929 and 1930 seasons, Haskell maintained a record of 8-2-0 and 10-1-0. The only loss in 1930 was to the University of Kansas, the following year, 1931, Haskell defeated Kansas in their re-match.

Rabbit Weller, a Caddo from Oklahoma who would go on from Haskell to play football professionally.

Buster Charles, an Oneida from Wisconsin led Haskell during this period of time and would eventually compete in the 1932 Olympics in the decathlon, a series of 10 events that commonly is said to determine the best all-around athlete in the world. Buster Charles finished 4th, just short of a medal.

Inadequate funding has always been an unresolved issue

In 1933 Haskell moved away from its collegiate schedule and returned exclusively to high school competition by 1938. Through the Great Depression of the 1930s Haskell’s budget was cut by one-third (1/3), and it struggled financially for a period of nearly fifteen (15) years, but was able to maintain both its educational standards and athletic programs for the hundreds of students who continued to enroll during the same period of time.

Tony Coffin (“Coffin”) began his coaching career at Haskell in 1938 when as an enrolled student at Kansas University he played baseball collegiately and was allowed room and board at Haskell. In order to pay for his Haskell room and board, Coffin was given the responsibility to coach Haskell baseball, boxing, and was utilized as an assistant in football. When the United States entered World War II on December 07, 1941, Coffin volunteered for military service in early 1942. At the conclusion of the War in 1945 he returned to Haskell to re-start his coaching career. In 1948 he took the reins as head coach in football, basketball, and track and field and by 1951 had Haskell athletics (at the high school level) back on the map, the football program between the years 1951 to 1961 compiled a record of 58-38-5. The basketball teams went to state championships twice (1953 and 1956), a remarkable feat considering the male high school enrollment never exceeded 200.

The track and cross-country teams never lost a conference championship for twelve consecutive years. Some of the outstanding athletes at the time included:

Ed Postoak (1951 to 1954) was All- State in football and a 4 year starter on the basketball team;

John Edwards (1952 to 1955) was an All-State halfback and the school’s 440 record holder;

Other team members were:

James and Elliott Ryal (1952 to 1956);

Willie Sevier 1954-56, state finalist in basketball;

Ken Bailey 1956-1959;

Dave Hearne 1957-60;

Ken Taylor 1958-1961;

Billy Mills 1954-1957, (future 1964 Olympics 10,000 meters gold medal winner;

Gary Sarty (100 yard record-holder) 1957-1960;

Danny Little-Axe 1958-1961;

Gerald Tuckwin (1957-1960);

Darrell Farris, High School All-American (1959-1962); and

Phil Homeratha (1958-1961).

Other team members included the following:

James and Elliott Ryal (1952 to 1956);

Willie Sevier 1954-56, state finalist in basketball;

Ken Bailey 1956-1959;

Dave Hearne 1957-60;

Ken Taylor 1958-1961;

Billy Mills 1954-1957, (future 1964 Olympics 10,000 meters gold medal winner;

Gary Sarty (100 yard record-holder) 1957-1960;

Danny Little-Axe 1958-1961;

Gerald Tuckwin (1957-1960);

Darrell Farris, High School All-American (1959-1962); and

Phil Homeratha (1958-1961).

In 1970 Haskell became an accredited junior college and through 1977 the school was able to maintain winning records with Cecil Harry being named the schools only juco All-American in 1971.

Since 1920 Haskell has had three individuals who have attended Haskell and where each received their initial training, and competed in the Olympics:

Emil Patasani (Zuni) a 1920 5,000 meter runner;

Buster Charles (Oneida), a 1932 decathlete; and

Billy Mills (Sioux), 1964, an Olympic Champion in the 10,000 meter run.

Over the years Haskell has had five coaches who were named to the American Indian Hall of Fame for either, coaching and/or athletic achievement:

Lone Star Dietz, served as the head coach 1929 to 1932;

Gus Welch, 1933 to 1934;

John Levi, 1935;

Tony Coffin, 1947 to 1966; and

Jerry Tuckwin, 1970 to 1994.

It is believed Phil Homeratha, long-time coach at Haskell, 1970 to 2012, the only Haskell coach to ever take three different Haskell teams to national basketball tournaments in three different decades, 1987, 1999, and 2008 will one day be in the National Indian Hall of Fame for his coaching achievements at Haskell.

This represents a summary highlighting some of the most significant moments in Haskell athletic history and provides only a brief lesson as to the tradition of Haskell athletics that has emerged over the years.

Unless those of us who appreciate the opportunity and life lessons Haskell has given us, their athletic program could possibly be either scaled down or termination of their athletic programs. So many Native American lives have been jumpstarted to successful careers and contributions to Indian Country because of the education received at Haskell. So many memories, experiences, and life lessons were provided ay Haskell. It’s hard to imagine a world without Haskell, a place where Native Americans who normally wouldn’t obtain an education beyond the limits of their reservations or urban difficulties. These students, past and present, felt more comfortable being around other Native Americans from all over the country. Different tribes, cultures and languages. But we all came from a world that didn’t and somewhat still hasn’t accepted us entirely or respected our culture and spirituality. Would you like to ensure that this traditional learning experience is there for your children, grandchildren and others in the future generations? Do what you can to keep the school open. So many struggling and goal oriented Native Americans who may not have somewhere else to go are depending on Haskell be there for their pursuit of excellence.

If any individual or tribe is concerned and would like to assist the Haskell Athletic Program, you can contact the Haskell Indian Nations University Athletic Department at 155 Indian Ave., Lawrence, KS 66046, Tel. (785) 749-8459.