By Kalvin Valdillez; photos by Wade Sheldon and Kalvin Valdillez

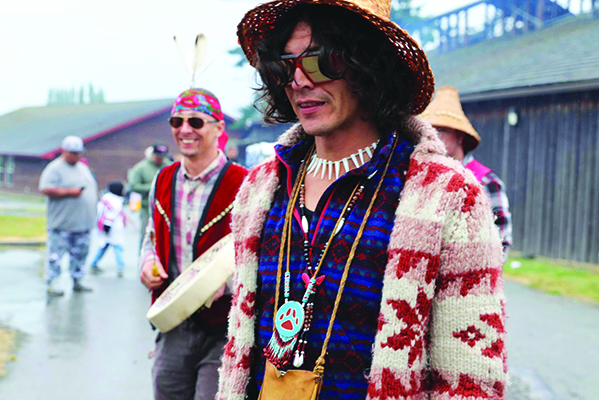

Hundreds of Tulalip members stood upon a small bluff overlooking Tulalip Bay. Draped in traditional garb, the women and young ladies adorned shawls and ribbon skirts while the men and boys wore vests and ribbon shirts. Cedar woven headbands, hats, and jewelry were the accessories of choice, as well as bandanas, eagle feathers, and beaded medallions. The kids gasped with excitement and pointed out into the distance of the bay. With traditional hand drums and rattles, the people sang hikw siyab yubəč, and greeted the first king salmon of the season to the village as he arrived at the shore on a cedar dugout canoe.

“Today is our 47th annual Salmon Ceremony, that was revived 47 years ago,” said Tulalip Chairwoman, Teri Gobin. “We’re honoring hikw siyab yubəč, big chief king salmon. Welcoming him and showing him how well our community will treat him, so he will go back to the village under the sea and let them know he was treated well at Tulalip. And we’ll have a bountiful season. And it will also bless our fishermen to protect them from the storms and the weather and make sure they come home safe.”

As one of the main staples of their ancestral diet, the relationship between the salmon and the sduhubš is strong. The traditional belief is that Tulalips are descendants of the Salmon People who live in a village under the Salish Sea. At the beginning of every fishing season, the king salmon send a scout to the waters of Tulalip Bay, and it is his duty to report back to the Salmon People about his time spent amongst the tribal nation.

In the early 90’s, Tulalip leader Bernie ‘Kai Kai’ Gobin penned a retelling of the traditional Tulalip story, the Salmon People, for the Marysville School District. Kai Kai shared, “The story goes that there is a tribe of Salmon People that live under the sea. And each year, they send out scouts to visit their homelands. And the way that the Snohomish people recognize that it’s time for the salmon scouts to be returning to their area is when, in the spring, a butterfly comes out. And the first person to see that butterfly will run, as fast as they can, to tell our chiefs or headmen, or now they are called the chairman. One of the other ways they recognize that the salmon scouts are returning is when the wild spirea tree blooms. The people call it the ironwood tree, and that’s what they use for fish sticks and a lot of other important things, like halibut hooks. It’s a very hard wood. So, when they see either one of these, a tribal member will tell the chairman, and he immediately sends out word to the people and calls them together in the longhouse for a huge feast and celebration to give honor to the visitors that are coming.”

Keeping with the tradition that extends across thousands of years, the Tulalip community prepares for the arrival of the scout weeks in advance. The tribe plans a special honoring for the salmon, thanking the local Indigenous species for providing healthy nourishment for the people year after year.

“This is a ceremony that our people have done since time immemorial, since we were salmon,” explained tribal member, Chelsea Craig. “It was a commitment to our people under the sea that we would carry on this tradition. And when colonizers came and tried to stop us from practicing our ways, it went underground. And our ancestors maintained that knowledge and passed it through oral traditions. And when it was safe for us to bring it back, our elders brought it back. It’s our responsibility to keep that going until there is no more time.”

Along with the practice of spiritual work, the Lushootseed language, songs, dances, hunting, gathering, and traditional ceremonies were outlawed by the US government at the beginning of the 20thcentury. During this time, Indian boarding schools were established, and children were forcibly removed from their families. The kids were to learn the ways of the ‘new world’ and abandon their traditional lifeways. It was a dangerous time to be Native American.

Decades passed by and the Salmon Ceremony was all but lost. However, thanks to a number of boarding school survivors, bits and pieces of those ancestral teachings were held onto while they endured the tragedies of assimilation. And in the mid-70’s, after the Meriam Report of 1928 helped abolish the majority of Indian boarding schools throughout the country, Harriette Shelton-Dover called upon her community. Forming a small group comprised of Tulalip, Swinomish, and Lummi elders, Harriette ushered in a new era for the sduhubš people with the revitalization of the Salmon Ceremony in 1976.

Teri recounted, “My father [Stan Jones Sr.] was one of the main people to work with the elders to bring the Salmon Ceremony back. A lot of these songs were almost lost. It was Harriette Shelton Dover and all these iconic elders that wanted to make sure this was carried on. That was so important. My mom was the one who brought the cakes, and we would visit and write everything down to keep it for future generations. And that’s what’s most important, that these young ones are learning now.”

Tulalip’s future, some merely a few weeks old, were fully immersed in the ceremony, with their regalia and ancestral knowledge on full display. Accounting for over half of those in attendance, the youth put on their sduhubš warrior faces and treated the gathering with the utmost importance and sincerity. Each time they entered the sacred space of the Tulalip longhouse, they went in focused on the work taking place and beamed with Tulalip pride.

“It felt so good in the longhouse,” exclaimed Chelsea. “It felt like we were bringing pride to our ancestors. It felt like a longhouse full of love. It felt good today. And to see all the kids, I was sitting down watching them, and it overwhelmed me with pride. Our young ones are taking up this culture with their full selves.”

Tulalip youth Rajalion Robinson expressed, “This was my first year at the Salmon Ceremony. It was really nice to learn more about my culture, especially during the practices. My favorite part of the ceremony was dancing to the Welcome Song.”

Upon witnessing the youth arriving at the year’s ceremony, Teri said, “It’s exciting because what it brings is all this culture and knowledge to the children so they can pass it on. I’m really excited about how many youth we have involved. We actually almost need a longer longhouse to accommodate all the children.”

In total, ten songs and blessings are offered at the Salmon Ceremony. And those powerful chants were amplified by all the voices of the young people this year. From start to finish, the kids were engaged and sang with booming voices that echoed out of the longhouse and rippled across the bay. The ten songs are offered in the following order:

- The Welcome Song

- Sduhubš War Song

- Eagle/Owl Song (Tribute to Kai Kai)

- Blessing of the Fisherman

- Listen to our Prayers

- hikw siyab yubəč

- The Happy Song

- Table Blessing Song

- Canoe Song (Kenny Moses Jr.’s Song)

- New Beginnings Cleansing Song (Glen’s Song)

Once the guest of honor is welcomed into the longhouse, he is escorted on a bed of cedar branches to the Greg Williams Court where a feast ensues. The people share the first bite of salmon together as one tribe.

“This first piece is representative of us all sharing the blessing of the yubəč,” said Salmon Ceremony leader, Glen Gobin, as he addressed the participants at the gym. “I ask that we all eat this piece at the same time together. Now, I’m going to ask that we all take our water and drink it together. This clear water represents the purity of life, and the lifegiving waters in which the salmon come from. Now I’m going to ask that we all eat this wonderful meal together.”

After the meal, the people return the remains of the scout back to the waters so he can complete his journey back to the village of the Salmon People and tell his relatives about his journey to the sduhubš territory. To show their appreciation to the tribe for the special honoring, the salmon will travel to Tulalip Bay throughout the season to continue providing sustenance for the people.

Derek Prather, Tulalip member and parent shared, “It’s a beautiful ceremony and I’m grateful to be able to share it with my kids, help cook the fish, and take part in the ceremony with the community. I’ve been doing it since I was my son’s age, 5 years old. My uncle was Stan Jones who helped restart the Salmon Ceremony, so it’s important to pass this on to my kids. I’m really grateful to see so many kids show up today. It warms my heart to see that.”

The following message is an excerpt from the 2023 Salmon Ceremony program:

This year’s Salmon Ceremony is dedicated to Donald ‘Penoke’ Hatch Jr. He was on the Tulalip Board of Directors for 27 years. And for every year he served on the board, he fought to keep the Salmon Ceremony and any activity for our youth alive here at Tulalip. Penoke was also on the Marysville School Board for 16 years to help keep our children in school. For all his hard work supporting our children, the Tribe named the new youth center gym after him. Our hands go up to him for all he has done for our tribe.

During the feast, and moments before taking a generational photo as a member of the king salmon carriers of the ceremony, Penoke shared a few words about the special honoring. He said, “Right now, I’m going through a lot with my health. I’m not feeling too good because of my cancer and the medicine I take. But it makes me feel good when I wake up in the morning to another day. Today was a really special day and it was tremendous for me. My life here on the reservation, all the cultural going-ons and all the things that I’ve done in my lifetime, it’s coming back to me. And I appreciate our people for recognizing me and the years that I participated in education, sports and just in our community. Our tribe has given us so many things that we need to appreciate more. We have to appreciate each other more. We have to love each other more than yesterday. That’s the most important thing.”