And how to fix it.

By Francie Diep, Pacific Standard

The Navajo Nation covers 27,413 square miles. Serving that entire area, the territory has just 10 grocery stores. This means that, in order to get fresh, affordable produce, some Navajo Nation residents must drive at least 155 miles round-trip, according to one recent study.

This makes the Navajo Nation, like many other American Indian reservations, a food desert—a region in the United States where residents can’t easily buy fresh, healthy, affordable food. (Because of their setting, these food deserts are unlike those that normally show up in the news, which tend to be in urban centers.) In recent years, American public health researchers and policy experts have done a lot to document the effects of food deserts on people’s health, and to suggest solutions. Yet, in all that talk, nothing quite seemed like it would work for the people Crystal Echohawk and Janie Simms Hipp serve. “The policy levers were off,” Hipp says. “They were not a good fit because of the uniqueness of Indian Country.”

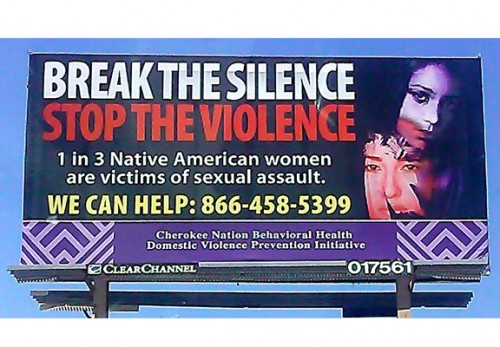

Hipp is an agriculture lawyer who directs a research institute at the University of Arkansas School of Law. Echohawk runs her own consulting firm in Colorado that advises non-profits working on American Indian issues. Together, they advocate for American Indians to gain better access to healthy food, which would in turn reduce rates of obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related ills that run rampant in the Native American population as a whole. Over 80 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native adults are overweight or obese; about half of American Indian children are at an unhealthy weight; and it’s estimated 30 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives have pre-diabetes. Compare those statistics to American adults in general, two-thirds of whom are overweight or obese, and 27 percent of whom are estimated to have pre-diabetes.

“Oftentimes, when conversations are had with policymakers or philanthropy or public health, people just turn away and say, ‘We don’t know where to start. The problems are too big for us to solve.’ But there’s no shortage of opportunity for real change.”

Conventional fixes probably won’t work. But Echohawk and Hipp have ideas for what will. Together with lawyer-activist Wilson Pipestem, they put together a report for the American Heart Association about how to address the unique burden of diet-related disease that the U.S.’s indigenous people carry. “I think, oftentimes, when conversations are had with policymakers or philanthropy or public health, people just turn away and say, ‘We don’t know where to start. The problems are too big for us to solve,'” Echohawk says. “But there’s no shortage of opportunity for real change.”

Pacific Standard recently talked over the phone with Echohawk and Hipp about what makes it hard to stay healthy while living on reservations and trust lands—what’s collectively called Indian Country—and how a local food movement and cultural programs can make it easier:

What are some examples of policy ideas for reducing obesity that weren’t good fits for Indian Country?

Janie Hipp: I’d served for six years or so with the Bush and Obama administrations at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. I was always struck when policy, at the national level, was really bearing down on food deserts. They talked about encouraging retail food outlets to carry more healthy food products or fresher produce. That’s great, but if you have no retail food outlet, then you’re actually talking about a whole different policy arena that you need to wrap your head around.

Crystal Echohawk: There’s just the assumption that people already had outlets, that they were in urban centers. There’s also the lack of understanding of tribes as sovereign nations and their ability to institute a level of policy change over their tribal citizens. Now, a lot of the policy change that is being advocated is at the state level. But when we really look at the biggest levers of change in Indian Country, we look at the level of tribal government and we also look at federal because of the government-to-government relationship that tribes have with the federal government.

I saw that the Navajo Nation this year instituted a tax on junk food. It also made fresh fruits and vegetables tax-free. I can’t imagine a state doing that. New York City tried to institute a sugary-drinks tax and it failed.

CE: There’s immense opportunity for real change in Indian Country. What Navajo Nation did, I think, is just one example. There are just so many more opportunities aside from a tax.

What’s one of your favorite ideas for improving healthy food access in Indian Country?

JH: The vast majority of the foods that are raised for human consumption on our reservations leave the borders of the reservation. If the levers are pulled in such a way that feeding people healthy, local food comes first, before you feed folks outside of those reservation boundaries—you can do both—then we are within reach of having a major shift in our health. And oh, by the way, [by selling locally grown food locally] we also can build strong rural and remote economies.

Why does all the food leave?

JH: What is lacking in all rural communities—it’s not just Indian Country, but the lack is more profound—is the infrastructure necessary to do the harvesting, grading, packing, storage, freezing, all of those things that allow you to store and move food around more locally. Re-building those infrastructure pieces, or building them outright, is an important piece that can’t be ignored.

What’s wrong with growing food on tribal land and having that shipped out, and then having something else shipped in, instead?

JH: Being able to retain as much healthy local food around our communities as possible is going to lead to fresher produce being available to us. On the meat side, that’s been a phenomenon for years, where livestock is raised on our reservations, but they leave the reservation boundaries and, in many cases, never return. Or they make a circuitous route across the U.S. before they get back. Think about the cost associated with that. All you have to do is go into a grocery store close by any of our remote reservations and you will noticeably see the cost of food is much higher, and that’s not even talking about Alaska.

Why do you think American Indians have higher rates of obesity and diabetes than Americans in general?

CE: Poverty is a root cause. It’s a lot cheaper to go to McDonald’s and order stuff off the Dollar Menu than it is to go in and buy fruits and vegetables in a store when you’re looking at many families that are surviving on one paycheck and feeding a dozen people.

Another important component is how we’re addressing historical trauma within Native American people. There’s been increasing research out there linking trauma to health disparities. When you look at the history regarding Native Americans, of forced removal, of genocide, the boarding schools, it’s layer upon layer of trauma that Native American people, over generations, have sustained