Click on the link below to download the September 2, 2015 syəcəb

September 2, 2015 syəcəb

syəcəb

EVERETT, Wash. – Collision Investigation Unit detectives are looking for information about the fatal collision that occurred last week which killed two men and two juvenile females on the Tulalip Reservation.

Specifically, they are looking for witnesses to the incident or surveillance video of the truck from around 1:30 a.m. on August 18th through the time the accident was reported later that morning (3:30 a.m.).

Detectives are seeking this information to help piece together what may have caused the incident, as well as additional evidence to aid in their investigation.

Anyone with information is asked to call the Sheriff’s Office anonymous tip line at 425-388-3845.

The incident occurred at the 7500 block of Totem Beach Rd. The pickup truck with the four victims went off the roadway, over a concrete embankment, and into a fisheries rearing pond. All four died at the scene.

by Kim Kalliber, Tulalip News

“Is this the world that we want to leave to our children?”

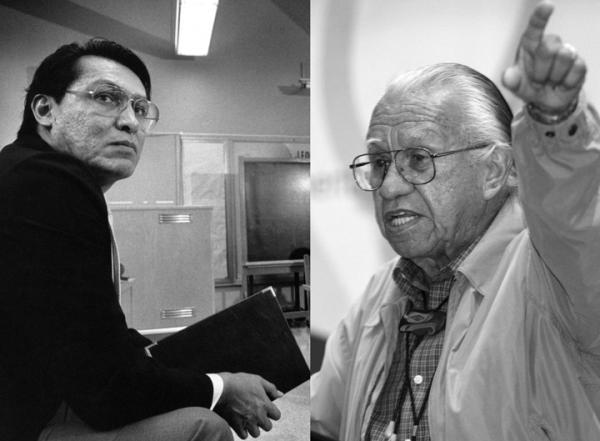

That is the question posed by Jewell James, Master Carver of the Lummi Nation’s House of Tears Carvers, of the numerous coal port projects around the northwest and beyond.

“We know the answer,” continued James. “We want our children to have healthy air, water and land.”

For the third year in a row, Lummi carvers have hand-carved a totem pole that will journey hundreds of miles, raising public awareness and opposition to the exporting of fossil fuels. And the timing couldn’t be more important, as the Army Corps of Engineers may be deciding by the end of this month whether or not it will agree with the Lummi Nation and deny permits for the Gateway Pacific Terminal Project at Cherry Point. Lummi Nation, in fighting to block the terminal, cited its rights under a treaty with the United States to fish in its usual and accustomed areas, which include the waters around Cherry Point.

“The totem pole design includes an eagle, a buffalo, two badgers, two drummers with a buffalo skull and drum, and a turtle with a lizard on each side. These are symbols of their culture,” explains James. “These people want everyone to know that they love the earth, they love their mother, and they want us to help them protect our part of the earth. “

On August 23, the Tulalip Tribes welcomed the totem pole and guests with songs and blessings. Tribal Chairman Mel Sheldon opened the ceremony and tribal member Caroline Moses led a blessing song for the totem pole.

“The salmon are already dying in the river because of the high temperature. The spawning grounds are poisoned. They [coal companies] have yet to feel the repercussions of that. They are walking away with their hands slapped. These ports, Cherry Point, Port of Morrow, we’re talking about 153 million tons [of coal] annually coming into the Pacific Northwest, loaded with arsenic and mercury,” said James to the group of tribal and community members gathered at the shores of Tulalip Bay. “We’re saying no; we’re united. We’re happy to be at Tulalip because Tulalip is a leader tribe.”

James went on to speak about the united effort to defeat these fossil fuel export projects, saying that, “nobody hears us, because the media doesn’t come to Northern Cheyenne.” The totem pole journey plays an important role in bringing people together, creating new alliances, and empowering the public with information about fossil fuels and the damage they are causing the environment.

“Pope Francis came out with a statement last year that they were wrong and they should have taught the people how to love the earth, not destroy it. They made a mistake. What we need to do as tribal people is to make sure that they live up to the words they put out publicly. We’re calling on everybody to join together. We need to get together because the Earth’s dying. July was the hottest recorded July in recorded history. The Earth is burning. Global warming is a reality and they’re syphoning our rivers dry. Our salmon, our fish, and everything else that depend upon it is dying around us.

“We say it simply, love the Earth. That’s the message that we’re bringing to Northern Cheyenne in unison with us.”

Seattle’s newest middle school will be named for the late Robert Eagle Staff, Lakota, principal of American Indian Heritage High School from 1989-1996.

The Seattle School Board voted June 17 in favor of the naming. “The extensive community engagement naming process has resulted in majority support to honor the accomplishments and legacy of a great educator, Robert Eagle Staff,” said Jon Halfaker, executive director of schools for the Seattle School District’s Northwest region.

“It’s huge” for the Native community, said the late principal’s son, Louis Eaglestaff, who spells his name as one word as his father did. Eaglestaff said the district chose to spell Eagle Staff as two words, out of respect for the wishes of family members in South Dakota who spell it that way.

No matter. “Even though he did so much for students, the school name is validation that [his legacy] is always going to be there,” said Eaglestaff, a kindergarten teacher in nearby Bellevue. “I don’t need validation, because what he did was enough for us. But it’s something to be proud of.”

RELATED: Two Native Leaders’ Names Among Those Being Considered for New Seattle School

Robert Eagle Staff Middle School will be built at the site of the former Wilson-Pacific School, which housed American Indian Heritage School. The new middle school will have room for 850 students, as well as 150 from the American Indian Heritage School program. It is scheduled to be completed in 2017.

The former Wilson-Pacific School site is important to Seattle’s Native community. It is the site of a spring, called Licton (Liq’tid), which is historically and culturally significant to the Duwamish people. American Indian Heritage hosted powwows and cultural programs for young people, and the buildings featured Native-themed murals by artist Andrew Morrison, Apache/Haida. The walls with the murals are being saved and will be incorporated into the new school buildings.

Getting the school named for Eagle Staff was part of a long effort by the Native community—an effort that continues now in trying to rebuild the American Indian Heritage program.

The school board’s vote “is the culmination of a two-year campaign which included active lobbying, a documentary, online petitions, many phone calls, tons of letters written in support, and community meetings,” wrote Sarah Sense-Wilson, Lakota, chairwoman of the Urban Native Education Alliance.

“The next fight is having a Native-focused high school in [Eagle Staff] school.”

During Eagle Staff’s leadership, American Indian Heritage High School had a 100 percent graduation rate with all graduates going on to college. Eagle Staff, a University of North Dakota Hall of Fame basketball player, passed away unexpectedly at age 43, and enrollment in the school he led started to decline amid changes in funding and program support.

The school buildings fell into disrepair as the district diverted funding to other priorities. By 2012, plans were developed to build a new school to accommodate projected enrollment growth and alleviate overcrowding in three other middle schools. In 2013, voters approved a capital levy to fund construction of several new schools and to modernize others. In 2014, the American Indian Heritage School program was merged with a program from another school, also closed for new construction, renamed Licton Springs, and moved temporarily to another site.

“Licton Springs is going to take another 3-5 years of development to reach a level of Native focus we think is authentic,” Sense-Wilson wrote in an email. “Still no Native staff, no language, no cultural programming at Licton. A majority of the kids are non-Native.”

Seattle Public Schools Superintendent Larry Nyland recommended the school board name the school in honor of Eagle Staff based on input at community meetings and comments from 190 members of the public. Supporters at the final community meeting on May 4 included members of Eagle Staff’s family. Only three people at the meeting spoke in favor of naming the school after another nominee, Dr. Caspar Sharples, an early 20th century Seattle physician and co-founder of Children’s Hospital. Other names considered included Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually (1931-2014), treaty rights activist and environmental leader.

A 660-student elementary school will be built adjacent to Robert Eagle Staff Middle School. The school board voted to name it Cascadia, after the geographic bioregion that includes Washington, Oregon and British Columbia. Other names nominated included author-poet-playwright Sherman Alexie, Spokane; author-poet-actor Maya Angelou; Josephine Corliss Preston (1873-1958), the first woman elected to state office in Washington; and Dr. Caspar Sharples.

Several indigenous nations have ties to Seattle, including the Duwamish Tribe, the Muckleshoot Tribe, and the Suquamish Tribe. Of 92 public schools in Seattle, only four have indigenous names: Leschi, the mid-1800s Nisqually leader; Sacajawea, the Lemhi Shoshone interpreter and guide for the Lewis and Clark Expedition; Chief Sealth (an anglicization of Si’ahl), the mid-1800s leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish; and Eagle Staff.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/07/12/seattle-school-named-after-robert-eagle-staff-fourth-have-indigenous-name-161015

By Brian Pempus, www.cardplayer.com

A Native American tribe with a casino in Michigan has stopped paying the state its cut because the state elected to offer lottery games on the Internet.

The tribe believes the state violated their revenue-sharing compact by launching online lottery products last summer. The compact was negotiated back in 2007.

The Gun Lake Tribe stopped making payments in June. The Michigan Economic Development Corporation receives roughly $60 million annually from the state’s tribal casinos. The Gun Lake Casino contributes roughly $13.3 million to the state annually.

According to crainsdetroit.com, other tribes may follow suit and stop their respective payments. Michigan has 12 tribes that have gambling facilities.

So far in 2015, online lottery sales have yielded $15.9 million for the state.

Americans spent more than $70 billion on the lottery in 2014, which makes it the most popular form of gambling in the country. More and more states are considering offering games on the Internet, with the most recent being North Carolina, according to a report from the Winston-Salem Journal. Florida is also considering bringing the games to the Internet one day.

State lotteries basically were given permission by the federal government to pursue online lottery services and products when the Department of Justice re-interpreted the Wire Act in December 2011. That move also resulted in three states launching online poker.

By Naveena Sadasivam, Insideclimate News

Four Western power plants that emit more carbon dioxide than the 20 fossil-fuel-fired plants in Massachusetts thought they would be getting a break under the Obama administration’s new carbon regulations––until the final rule ended up treating them just like all the other plants in the country.

The plants are located on Native American reservations, and under an earlier proposal, they were required to reduce emissions by less than 5 percent. But the final version of the rule, released earlier this month, has set a reduction target of about 20 percent.

A majority of the reductions are to come from two mammoth coal plants on the Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico—the Navajo Generating Station and the Four Corners Power Plant. They provide power to half a million homes and have been pinpointed by the Environmental Protection Agency as a major source of pollution––and a cause for reduced visibility in the Grand Canyon.

These two plants alone emit more than 28 million tons of carbon dioxide each year, triple the emissions from facilities in Washington state, fueling a vicious cycle of drought and worsening climate change. The two other power plants are on the Fort Mojave Reservation in Arizona and the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in Utah.

Environmental groups have charged that the Navajo plants are responsible for premature deaths, hundreds of asthma attacks and hundreds of millions of dollars of annual health costs. The plants, which are owned by public utilities and the federal government, export a majority of the power out of the reservation to serve homes and businesses as far away as Las Vegas and help deliver Arizona’s share of the Colorado River water to Tucson and Phoenix. Meanwhile, a third of Navajo Nation residents remain without electricity in their homes.

Tribal leaders contend that power plants on Indian land deserve special consideration.

“The Navajo Nation is a uniquely disadvantaged people and their unique situation justified some accommodation,” Ben Shelly, president of the Navajo Nation, wrote in a letter to the EPA. He contends that the region’s underdeveloped economy, high unemployment rates and reliance on coal are the result of policies enacted by the federal government over several decades. If the coal plants decrease power production to meet emissions targets, Navajos will lose jobs and its government will receive less revenue, he said.

Many local groups, however, disagree.

“I don’t think we need special treatment,” said Colleen Cooley of the grassroots nonprofit Diné CARE. “We should be held to the same standards as the rest of the country.” (Diné means “the people” in Navajo, and CARE is an abbreviation for Citizens Against Ruining our Environment.)

Cooley’s Diné CARE and other grassroots groups say the Navajo leaders are not serving the best interest of the community. The Navajo lands have been mined for coal and uranium for decades, Cooley said, resulting in contamination of water sources and air pollution. She said it’s time to shift to new, less damaging power sources such as wind and solar.

The Obama administration’s carbon regulations for power plants aim to reduce emissions nationwide 32 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels. In its final version of the rule, the EPA set uniform standards for all fossil-fueled power plants in the country. A coal plant on tribal land is now expected to achieve the same emissions reductions as a coal plant in Kentucky or New York, a move that the EPA sees as more equitable. The result is that coal plants on tribal lands—and in coal heavy states such as Kentucky and West Virginia—are facing much more stringent targets than they expected.

The EPA has taken special efforts to ensure that the power plant rules don’t disproportionately affect minorities, including indigenous people. Because dirty power plants often exist in low-income communities, the EPA has laid out tools to assess how changes to the operation of the plants will affect emission levels in neighborhoods nearby. The EPA will also be assessing compliance plans to ensure the regulations do not increase air pollution in those communities.

The tribes do not have an ownership stake in any of the facilities, but they are allowed to coordinate a plan to reduce emissions while minimizing the impact on their economies. Tribes that want to submit a compliance plan must first apply for treatment as a state. If the EPA doesn’t approve, or the tribes decide not to submit a plan, the EPA will impose one.

By Associated Press

PINE RIDGE (AP) — A longtime tennis coach in England has been offering free tennis classes on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Leigh Owen, 50, has been visiting Pine Ridge regularly since 1997 and has been enamored with the people and their culture since he was an 8-year-old boy, when he asked his mom to write to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, he told the Rapid City Journal.

“I don’t know exactly why,” Owen said by phone, “but I was interested in the Native-American culture since childhood.”

Owen began coaching at Red Cloud Indian School in February, spending one day a week at the school. Although Red Cloud does not have a formal tennis court, the school’s gym is perfect for what Owen calls “mini-tennis,” allowing his students to work on technique.

“The kids really liked it,” he said.

Patrick Welch, a physical education teacher at Red Cloud Elementary and assistant athletic director at the middle school, said Owen is doing an amazing job. Welch said kids on the reservation know basketball, football and cross country running, but tennis was foreign to them.

“Leigh got the kids interested; he grabbed their attention right off the bat,” Welch said.

Owen said the United States Tennis Association has been generous in providing equipment for the fledgling tennis players.

Tony Stingley, director of training and outreach for USTA’s northern district, estimated that the organization has donated more than $1,200 worth of equipment.

Owen said he is determined to turn the reservation he loves into a mecca for the sport he loves, and he and Welch are thinking big. They want to renovate some outdoor courts for what could become a tennis center.

Owen is back in Liverpool but will return to the United States in early September.

By the Associated Press

KESHENA, Wis. — Members of the Menominee Indian Tribe have endorsed the possible legalization of marijuana for medicinal and recreational use on their northeastern Wisconsin reservation, the tribe announced Friday.

In what tribal leaders called an advisory vote, about 77 percent of members voting said they backed medical marijuana. The vote was closer on recreational use, with about 58 percent of voting members saying yes.

Chairman Gary Besaw said tribal legislators will now study whether to move forward on both issues. He didn’t have a timetable for how quickly that might happen.

The Justice Department announced in 2014 it would let Indian tribes legalize and regulate marijuana, but most tribes have been reluctant to move forward with the new freedom for concern about possible public safety and health consequences. Besaw said the Menominee “have to be cautious.”

“This is all new ground we’re breaking,” Besaw said. “It’s hard to get definitive answers.”

Asked whether the tribe would consider commercial sales — selling marijuana to non-members — Besaw said only that the tribe would defer to the U.S. attorney’s office in Wisconsin in interpreting the Justice Department’s 2014 memorandum. In South Dakota, where the Flandreau Santee Sioux has announced plans to develop a pot-selling operation, the U.S. attorney has warned that non-Indians would be breaking the law if they consume pot on the reservation.

Greg Haanstad, the acting U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Wisconsin, had no comment, a spokeswoman said.

Besaw noted the easier vote on medicinal marijuana.

“People more clearly understand the benefit of medicinal marijuana,” Besaw said. “Even those who voted no on the recreational have said … we know there is value in medicinal marijuana and there clearly are individuals who benefit from it.”

Assembly Majority Leader Jim Steineke, R-Kaukauna, said in a statement he was disappointed in the tribe’s vote, saying eventual legalization could pose “serious challenges for law enforcement.”

About 13 percent of the tribe’s 9,000 members cast ballots.

The possibility comes on the heels of the tribe’s unsuccessful effort to open a casino in Kenosha.

Dylan Dale Monger was born April 1, 1993, in Seattle, Wash., went to be with the creator on August 18, 2015.

Born to Lisa Anne Monger and Robert Wade Monger Dylan was raised in Tulalip, Wash., he attended Tulalip ECEAP, Tulalip Elementary school, then went onto Quil Ceda elementary and Totem Middle school. Then moved onto Arts and Tech where he learned to flirt with girls and write notes.” As his Dad would say “School of Hard Knock”. Dylan loved the outdoors, hiking camping just spending quality time with his “HOMIES” enjoyed and loved good times at the river (Big Rock and the Bridge at Sylvania) with his friends and family. Dylan was creative with his hands he loved building and creating gifts for those he loved. Dylan was a master of all trades which he learned many skills from his Dad. Dylan loved to cook he shared many good meals with his ” HOMIES” and family, Dylan loved to laugh, he created many stories and shared then freely with everyone that would listen, Dylan always had a good prank to pull. Dylan’s heart was so big and he loved to love and was easy to love by his friends and family.

Dylan is survived by his mother, Lisa Monger, father, Robert “Whaakadup” Monger; grandmother, Mary Lou Kelly; sisters: Jennifer Monger, Danielle Monger (Elias Ruiz), Brittany Monger (Joshua “JT” Anglim), brothers, Joel Keeline; uncles: Jon Granath, Craig Granath, Charlie Vassar, Mark Monger Sr., Dan Hankey (Kathy); aunties: Kathrine Monger, Anita Rodgers (Randy), Lucinda Cladoosby, Tina Pacheco, Rose Webb (Kevin) Annie Rowley (Bruce), Stacy Councilman (Craig) Kerrie Kelley: cousins: Joey Peltier, Michael Contraro, Joe Henry Sr., Vince Henry, Richard Henry, Dushane McGavin, Brenda Knight (Vern) Sam Knight, Cristina Cladoosby, Elisha Pacheco, Alisha Pacheco, Cyrus Pacheco, Vanessa Flores, Anita Taylor, (Scott) Adam Vassar, Damon Hatch, Maggie Stewart (Miles), Willie Webb, Lexi Webb, Mark Monger Jr, (Kara), Thomas Monger (Josh), Nicole Monger (Justin), Lindsey Granath, Julie Webb, Michelle Fitzgerald; nieces and nephew: Wesley, Autumn, Julianna, Kiara, Alexia, Izzy, Sajali, Leondra, Nathan, Ryan. Dylans Ride or Die Partner Damon (BUKKA) Charles. Alex Charlie; girl friend, Nikkie Mercier; and many, many loved ones.

Dylan was preceded in death by grandparents: Irene Granath, Jon Granath, Hirontimus Monger, Magdaline Monger, Peter Granath: and many more there to greet him on the other side.

There will be a visitation at Schaefer-Shipman at 1:00 p.m. on Tuesday, August 25, 2015, with an evening gathering at the family home at 6:00 p.m. The Funeral Services will be held Wednesday at 9:00 a.m. at the Tulalip Gym with burial to follow at Mission Beach Cemetery. Arrangements entrusted to Schaefer-Shipman

Tyson Daniel Walker, 21 of Tulalip passed away in an accident on August 18, 2015.

He was born to Cedrick Walker and Crystal Baggarley in Seattle, Wash. on June 30, 1994, at the University of WA Hospital. Tyson was a true 12th man for the Seattle Seahawks.

Tyson is survived by his mother, Crystal Baggarley; his father, Cedrick Walker; his siblings, Tashina Lundgren, and Travis Stevens; great-grandmother, Florence Baggarley; aunts, Kathleen Morse and Cleme; uncles, J. Daniel Perry, Conan Kopp, Cecil and Chris Walkers; niece, Estella Lundgren; nephew, Chase Hyle; and cousin, Alex Morse.

Visitation Monday, August 24, 2015, at 1:00 p.m. at Schaefer-Shipman with an Interfaith service to follow at 6:00 p.m. at the Tulalip Gym. The Funeral will be Tuesday at 10:00 a.m. at the Tulalip Gym with burial following at Mission Beach Cemetery. Arrangements entrusted to Schaefer-Shipman