By RICHARD MAUER Anchorage Daily News

rmauer@adn.com June 30, 2014

An expert testifying in the federal voting rights trial in Anchorage said Monday it’s possible to trace Alaska’s current failure to provide full language assistance to Native language speakers to territorial days when Alaska Natives were denied citizenship unless they renounced their own culture.

“This represents the continuing organizational culture, looking at the law as something they’re forced to do, instead of looking at the policy goal of being sure that everyone has the opportunity to participate,” said University of Utah political science professor Daniel McCool. “It’s part of a pattern I see over a long period of time, a consistent culture — they’re going to fight this. When forced to do something, they’re going to do it, but only when they’ve been ordered to.”

McCool testified as an expert on behalf of four tribal villages in Southwest Alaska and the Interior and two village elders with limited English skills. They’re suing Lt. Gov. Mead Treadwell and three officials in the Alaska Division of Elections which he oversees, saying the officials are not providing a full suite of election materials in their Native languages. They say amendments to the Voting Rights Act in 1975 require language assistance.

The state says it’s doing what the law requires, providing sample ballots and oral translations for some Native languages. The state has gone out of its way to consult with tribal councils, its witnesses have said.

Treadwell and the other officials are being defended by the Alaska Attorney General’s office. Before the trial began, the state lawyers attempted to prevent McCool from testifying, saying he wasn’t really an expert. They said he wasn’t familiar with Alaska and only spent four weeks or so researching how the state has treated Native voters over the years.

McCool said he may not be an expert on Alaska, but he knows how to study the issues. He said he reviewed tens of thousands of pages of documents, books, legal decisions, state and federal data and other material.

U.S. District Judge Sharon Gleason, a former state judge who’s hearing the case without a jury, disagreed with the state’s attorneys. She allowed McCool to take the stand and admitted the report he prepared for the Native plaintiffs.

McCool’s testimony came at the close of the Natives’ case, the sixth day of trial. The trial is expected to conclude this week.

McCool said that with some exceptions pushed by a few political leaders, Alaska’s history is rife with discrimination against Native voters. In 1915, the Territorial Legislature passed a law that said that for Alaska Natives to become citizens, “they had to give up their culture, their language, and live like white people,” McCool said. “They’re the only group in American history told to give up their identity in order to vote.”

In 1924, Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, granting Native Americans full rights as citizens. The response in Juneau? The following year, the Territorial Legislature passed a literacy test that kept most Natives from voting, McCool said.

“There was a fear that if they all became citizens, they would all start voting in dramatic numbers,” McCool said. One local newspaper ran an ad warning, “We don’t want these ignorant savages to take over,” he said.

McCool said one effective opponent of racism against Alaska Natives was the territorial governor Ernest Gruening, sent to Alaska in 1939 by President Franklin Roosevelt.

Assistant Attorney General Margaret Paton-Walsh was poised to object to McCool’s testimony if he strayed beyond what he was allowed to say. She took to her feet while McCool was testifying about Gruening’s autobiography, when two pages of a book were projected on a screen in the courtroom.

“Objection,” Paton-Walsh said. Reading from the folio on the book’s pages, Paton-Walsh said McCool was actually reading from the book “At War” by author Mary Bettles.

After a moment of confusion, McCool clarified: The folio didn’t say Mary Bettles, it said “Many Battles,” the name of Gruening’s book. The chapter heading in the other folio was “At War.”

A moment later, Gleason declared a break. When she returned from chambers and trial resumed, she said of herself and her clerk, “We both enjoyed ‘Mary Bettles.’ ”

McCool noted that Gleason herself played a role in Native rights issues when she was a state Superior Court judge and ruled in the case Moore v. State. She held that the state had failed to live up to its duty in the Alaska Constitution to provide public education in rural Alaska in 2007. Two years later, when the state Department of Education asked her to declare it was in compliance with the law and end her supervision of its remedial action, she refused, using language similar to that in McCool’s description of the Division of Elections. She said the state was applying an “incremental, minimalist initial approach” that didn’t pass constitutional muster.

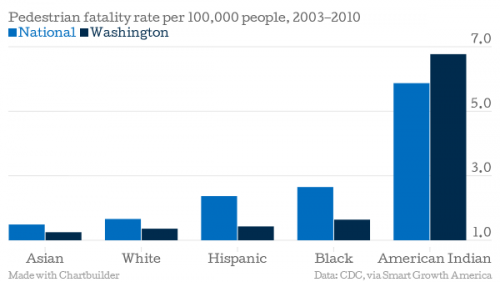

Education matters, McCool said, and poor schools in the Bush are closely connected to limited English proficiency among Alaska Natives.

McCool said Alaska didn’t abandon its literacy test until the U.S. Voting Rights Act required it to.

Under cross examination by Paton-Walsh, he acknowledged that the literacy test wasn’t as tough and discriminatory as ones in the South directed against African-Americans, but it had an intimidating effect.

McCool said he understood that the Division of Elections says it doesn’t have the resources to provide full language assistance for all Native speakers, but he said that’s only an excuse.

“These attitudes and behaviors don’t look to me like the behaviors of an agency that’s absolutely devoted to providing equal opportunity to all voters, even if it’s difficult,” McCool said. “The attitude is let’s do what the law requires and absolutely no more.”

Reach Richard Mauer at rmauer@adn.com or (907) 257-4345.