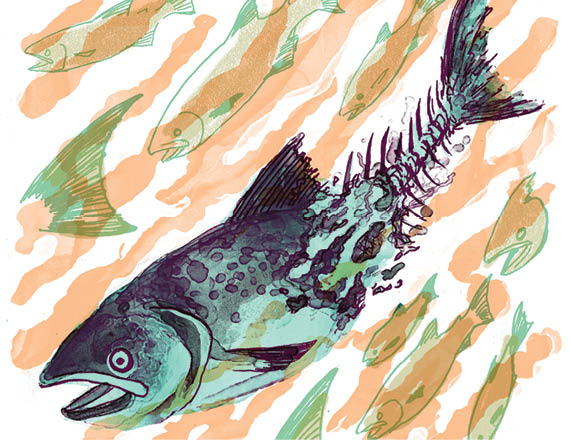

Tulalip tribal member Tony Hatch presents the first salmon of the fishing season during a Salmon Ceremony on the Tulalip Reservation in 2004. The traditional ceremony honors the first salmon to be caught with the hope that the fishing season will be plentiful. Following a feast, the bones of the salmon are returned to the water so that the honored fish will speak highly of the tribe.

By Les Parks, Source: The Herald

Puget Sound is one of the iconic wonders of the world and defines who we are, not only as tribes, but all residents of Western Washington.

This great body of water was still being formed by receding glaciers when the tribes arrived, and we have lived off her abundant natural resources ever since. Over thousands of years our beautiful and unique inland sea has become a complex ecosystem, supporting not only an abundance of sea life, but also mixing with freshwater resources at the mouths of our great rivers, providing a consistent and plentiful food source for us humans.

This natural resource wealth has influenced every part of our tribal traditions. Stories of the great salmon runs have been carried down through the generations, and they tell us these waters once rippled with silver, as salmon arrived home after several years out to sea. The clams, crab and mussels were also abundant, and along with berries, roots and the plants we harvested, our traditional diet was, and continues to be, sacred to us.

The old Indians used to say, “When the tide is out, the table is set!”

For more than 200 years the descendants of the settlers, and now peoples from around the globe, have called the Puget Sound home. Like the tribes, they have lived off her rich resources, appreciated her great beauty and passed laws to protect her from exploitation.

Today, however, the health of Puget Sound is failing fast. In recent years it has lost 20 percent, or more, of the plankton that makes up the base of our food web. Everything above plankton in the food chain is also affected and is showing signs of great stress. The loss of plankton is beyond comprehension and is the single greatest barometer of what is happening to the waters we have all largely taken for granted.

It is time the citizens of Washington, and in particular citizens of Puget Sound, act on this information. With plankton gone, it means every animal up the food chain pays the price, including us.

Mark my words: Puget Sound is dying! Finding whales dying from natural causes is expected. Finding whales that are emaciated and starving is alarming and will become a common scenario if we do not address the problem quickly. But what is happening; why are plankton dying? We are only beginning to understand the complex interactions between warming ocean waters, how they affect the state’s inland sea, and how human activities play into this alarming situation.

Toxins in the food chain are devastating from the bottom all the way up. Recent evidence suggests that nutrient pollution, such as nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater treatment plants, septic systems, residential homes, agriculture and other sources, are significantly disrupting the food web in Puget Sound. We cannot continue to ignore the fact that the sound is the baseline of our livelihoods and that we humans are only as healthy as our environment.

The great waters and rivers of the Salish Sea have existed since the last ice age (13,000 years ago) and with the melting of the ice the Puget Sound was born. Mother Nature has created this beautiful place we call home, and in less than 200 years, and largely within the last 100 years, we have managed to undo what Mother Nature provided us.

How many more years will it take to entirely wipe out sea life in Puget Sound? Can she sustain the barrage of pollutants that are killing the plankton for another 50 years? Do we have another 25 years to act before reaching the tipping point, or have we already arrived? Our window of opportunity to heal her is closing. It is our duty to do all that we can to improve her health and time is not on our side.

The Tulalip Tribes have collaborated with governments, nonprofits, and other entities on a variety of habitat restoration projects, on and off reservation, and we continue to lobby for the protection of Puget Sound. One project that we feel very proud to be a part of is Qualco Energy. Partnering with farmers and environment groups in the Snohomish River basin we have worked together to build an anaerobic digester, which channels cow manure away from streams and fresh groundwater sources by converting it to electricity before it is sold to the electricity grid. It is an example of the type of collaboration it will take to restore the health of our Sound.

Gov. Jay Inslee announced his proposal this week to address the issue of fish consumption that has large implications for our health and water quality standards. Gov. Inslee’s proposal begins to address Puget Sound’s health but not to the level that we had hoped. While the proposed rate of fish consumption is significantly higher, his proposal also increases the risk of cancer deaths by some toxins. The governor’s proposal strengthens water quality with one hand, but weakens it with the other. The net effect seems to be a very modest change for some chemicals, and no change at all for others. It also represents yet another delay on committing to the health of the Puget Sound, and to the health of those who depend on its resources.

There are no winners in the governor’s announcement. We want to be able to encourage our people to eat more fish and shellfish, as it sustained them well for many generations, and forms the basis of our shared ways of life. We remain hopeful that the court of public opinion will convince the governor to reconsider his proposal so that when the tide is out it is safe to eat at the table.

Les Parks is the vice chairman of the Tulalip Tribes.